![]()

Chapter 1

“In the Evening by the Moonlight”

The Minstrel Era and the Beginnings of Tin Pan Alley

THE FIRST STOCK CHARACTER TO RECUR ON the American stage was the “Jonathan” figure, a plain-speaking Yankee who mocked the Anglophiles around him in a handful of plays of the mid-eighteenth century. “Jonathan” was soon joined by another American type, an eccentric “Negro boy,” who was by turns comic and pathetic. At first the “Negro boy” was so peripheral to the plots of the plays that he was nameless, but over the years, as audiences began to look forward to his songs and mangled wordplay, he acquired names, “Mungo” and “Sambo” among them. (Lewis Hallam was the first “Mungo,” in a 1769 play called The Padlock.) He became a dependable source of fun, and by the early 1800s a few American actors had begun to specialize in the blackface delineation of him.

One of these actors was Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice, a gangly New Yorker who had begun as a spear carrier in plays in his native city. In 1828, his career as one of the first song-and-dance men took him to Louisville, where he devised a bit of material that would change theatrical history. He drew his inspiration from the singing and the shuffling step of a crippled black stable hand who worked near the theatre. Rice decided to impersonate the old man in his act, and in doing so, he created the first and most devastating of the minstrel stereotypes.

“Jim Crow” arrived full-blown at Rice’s next stop, in Pittsburgh. Wearing the stable hand’s shabby clothes, which he had purchased to add “authenticity,” Rice, in blackface and wooly wig, sprang at his audience, eyes rolling, wagging a finger, and doing a grotesque hop as he sang in a thick dialect:

W’eel about and turn about

And do just so,

Eb’ry time I w’eel about

I jump Jim Crow.

The onlookers were paralyzed with delight at this spectacle. Then they shot from their seats, screaming their approval. Daddy Rice had, in a stroke, given the American public the performance and the character it had been waiting for. Rice found that Jim Crow was a hit everywhere he went. (In 1833 Rice experimented by giving Jim a partner in the act. The little blackfaced boy he pulled out of a sack that he carried on stage was Joseph Jefferson, who would become one of the most beloved American actors.) After four years of trooping Jim around the South and Midwest, Rice took his misshapen darky to New York in 1832, then to London in 1836. Jim Crow became Rice’s signature character, played in every performance he gave until his death in 1860 and often in theatres so crowded that seating had to be placed on the stage around him. Rice’s caricature inspired dozens of imitators, and Jim Crow—the shuffling, brainless, eager-to-please black bumpkin—was off on his own career. He would haunt American stages, and black performers, for a hundred years.

The second classic stereotype to enter the minstrel pantheon was Jim Crow’s opposite number—“Zip Coon,” the citified black dandy, overdressed in his “long tail blue” coat and tight silk pants, brash and pretentious, eager to show his country cousins the latest dance steps and to confound them with his jokes and riddles. Zip Coon was the creation of a contemporary of Rice’s, the “Negro delineator” George Washington Dixon. Like Jim, Zip had his own theme song (the “Zip Coon” melody is now known as “Turkey in the Straw”), borrowed from a folk song, as Rice had borrowed his. Between them, Jim and Zip constituted a catalog of human frailties: ignorance, vanity, cupidity, and laziness. Both were harmless, sexless, hopeless. And both were painted black.

Given the enormous popularity of Rice, Dixon, and their blackfaced disciples, it was inevitable that someone would figure out how to combine their beloved characters with suitable “darky” songs to make a full evening of fun. The inevitable occurred in New York City in January 1843, when four out-of-work circus performers met in a boarding house and decided to cast their lots together, each in the hope that four unknown entertainers would draw an audience better than one. They called themselves the Virginia Minstrels. In early February they did short sets of their material between the acts of plays in New York, first at the Chatham Theatre, then at the Bowery Amphitheatre. Audiences enjoyed them, so they kept at it. In March 1843, at Boston’s Masonic Temple, they gave the first full-length minstrel show.

Dan Emmett, the most versatile of the four, played banjo, violin, and flute. Billy Whitlock was also a banjoist. Frank Brower played the bones (the poor man’s castanets—in Brower’s case, made of the actual ribs of a horse). Dick Pelham rounded out the rhythm section with his tambourine. They paired off for bits of crosstalk, and they accompanied each other during solo songs. After some success in the Northeast, the Virginia Minstrels began a tour of England. Although they were well received there, professional jealousies among them caused them to break up the act before their tour was over. The original Virginia Minstrels lasted only about six months, but their show concept was quickly taken up by others.

The first important minstrel impresario was Edwin P. Christy of New York. Christy’s troupe began small—four people at first, including the producer—but it was more professional than the Virginia Minstrels from the beginning. A better producer than performer, Christy saw the need for a structure and a context in which a minstrel entertainment could happen, a “natural” setting for blackfaced fun and music. Drawing his inspiration from actual slave entertainments he had heard about, Christy envisioned an evening that would represent a sort of festival on a showbiz plantation. Cheerful black neighbors in outlandish costumes (dressed up and dressed down) would come together to entertain each other—and the audience—with jokes, dancing and songs. The characters would play off each other’s foolishness, and the music would be strictly “Ethiopian”—that is, the humble banjo, tambourine, and bones would be the foundation of everything. Devoid of any relation to reality, yet advertised as completely “authentic,” the Christy show—and the dozens that followed it—presented slave life as a nonstop party in a darky Eden. Everybody sang, nobody worked, nobody got whipped, nobody was sold. The formula was so successful that, in a time when a one-week booking was a long stay, Christy’s Minstrels were in residence at New York’s Mechanics’ Hall for ten years.

The public loved the roaring, low-class energy of the minstrel shows and flocked to see the dozens of troupes that sprang up during the 1850s and 1860s. Any town large enough to have a railroad station and a hall could host a minstrel show. Any town small enough to have only a railroad station and a hall usually saw no other professional entertainment except minstrel shows for a generation in the mid-century.

With so much competition on the field, the shows grew grand and bloated trying to outdo each other. Entire railroad trains were needed to transport sets and personnel. Producers sent advance men to paste up garish three-sheets heralding the imminent arrival of “Gigantic Minstrels,” “Mammoth Minstrels,” and “Mastodon Minstrels,” shows big enough to shake up any small town and most cities in America. But no matter how huge or slick the presentations became, the idea of the “neighborhood party” given by black buffoons did not wear out its welcome for fifty years.

E. P. Christy prided himself especially on his troupe’s music. In September 1847 he discovered the work of a twenty-two-year-old songwriter from Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania, named Stephen Foster. Foster, from a middle-class family and self-taught in music, had been peddling his songs to minstrel performers, Daddy Rice among them, with no success. But when Christy heard a singer named Nelson Kneass perform Foster’s polka-paced “Oh, Susanna” in a variety show at Andrew’s Eagle Ice Cream Saloon in Pittsburgh, he quickly saw its possibilities for the minstrel stage. After several hearings, Christy remembered enough of the melody and words to pass them on to one of his singers. “Oh, Susanna” became the hit of Christy’s show. People not only wanted to hear the song, they wanted to buy it. A Cincinnati publisher, W. C. Peters, wrote to Foster, asking for the manuscript. Foster, still the amateur, sent it, no questions asked. The composer was delighted when Peters sent him a fee of $100. The song was published with the Christy name all over it (and Foster’s nowhere on it). Foster did not know that he had written the hit of the 1848 minstrel season until a friend sent him a copy. Emboldened by the fact that he had written something good enough for Christy to steal, Foster quit his day job in a Cincinnati office and began to think of himself as a professional songwriter.

There is no evidence that Foster and Christy ever met, but the pilfered song began a symbiotic relationship that would last the rest of Foster’s life. He would send Christy dozens of songs over the years—along with wheedling letters about payments and composer credit—and Christy used many of them in his various minstrel companies.

This arrangement, one-sided as it was, solved for Foster the nineteenth-century composer’s biggest problem: distribution. Songwriters of his time usually had their work published—or they self-published—only to have a small flurry of local sales, followed by the song’s disappearance from the printshop window. With Christy behind them, the Foster songs got national attention. They were sold in theatre lobbies after performances, and wherever the Christy troupe went, Foster’s songs went, too. Although his mentor and his publishers were neither scrupulous nor punctual with their payments and accounting to him, Foster was at least able to eke out a living as the first American songwriter who was not a performer, teacher, or church musician.

Throughout the 1850s Foster songs enlivened minstrel evenings: “Camptown Races,” “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Old Dog Tray,” “Old Black Joe,” “Massa’s in de Cold Ground,” and “Ring de Banjo” were among the nearly 200 published. Foster had a strong melodic gift and a good ear for the banjo-based syncopation of the minstrel stage. His songs achieved the instant status of “folk material,” appropriated and unpaid-for by the hundreds of minstrels who sang them.

In 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s blockbuster novel, was published, and it was read, discussed, and argued about for years. It presented more fully drawn African-American characters than any novel or play before it, and minstrel producers seized on three of the books figures to become stock players in the plantation comedy of their shows. The first was Uncle Tom himself—sometimes called Uncle Silas, Jasper, or Eph by minstrel producers—who became a wistful old man longing for the good old days on the plantation and reminiscing about them in song. (The kindly old Uncle began to get more stage time after the Civil War, when the good old days were really gone.) Aunt Chloe—sometimes called Dinah or Jenny—also entered the minstrel scene. She was the bossy peacekeeper and general scold of the shows’ antebellum fantasy land. Minstrel pros referred to her as “the wench role,” and, to compound the merriment, she was always played by a man. (Aunt Chloe would evolve into the more generic—and gentler—Mammy in the early 1900s.) Mrs. Stowe’s Topsy, the sprightly, mischievous pickaninny, provided a role for child actors on the minstrel stage. These three Stowe characters, along with Jim Crow and Zip Coon, completed the cast of archetypes for minstrel humor.

Along with the setting and characters, a proscribed format—a certain and unvarying playing order—for minstrel shows was in place by 1860. We cannot know who, if anyone, deserves the credit for figuring out this framework, but somehow, in the blur of activity of the minstrels’ first decade, everyone seems to have agreed on it. As specific as a recipe, this structure was found to be foolproof by troupes of all sizes, however rich or poor in production values or talent. Everyone knew that a minstrel show had to have a First Part, an Olio, and an Afterpiece/Walkaround.

The First Part began with a clattering overture, a medley of songs that would be featured during the evening. The curtain opened to reveal the troupe in all the splendor of setting and costume it could muster. In the center of a semicircle of gaudily dressed blackfaced comedians sat the master of ceremonies, Mister Interlocutor, a dignified, spiffily dressed white man. The two principal funmakers, Mr. Tambo and Mr. Bones—the Jim and Zip figures—were seated at opposite sides of the stage on the ends of the semicircle (hence, called “end men”). All arose to sing a welcome and a promise of a good time. At the finish of the opening song, the Interlocutor gave his ritual cry, “Gentlemen, be seated!” Then the first burst of snappy patter among the Interlocutor and his end men began, laced with local references, of course. The Interlocutor was slightly pompous but patient with the foolery of his fellows, bemused by the ignorance all around him. The puns and conundrums of Tambo and Bones were greeted by the laughter and stylized appreciation of the others on the front row. A synchronized raising and shaking of their tambourines punctuated the jokes. A singer, usually a tenor, stepped forward to perform a sentimental song with all the stops out. Then more jokes, a specialty dance (an early one was the “Virginia Essence,” the forerunner of the soft shoe), more crosstalk, and a First Part finale performed by all.

Next came the Olio, a set of various individual specialties usually performed “in one”: before the front curtain to allow the changing of scenery for the final part of the show. Instrumentalists, especially those trick players who could manipulate two clarinets, play tuned water glasses, do animal imitations on their horns, and the like, as well as jugglers and comic singers—all got to show their stuff in solo turns. But the indispensable part of the Olio was the stump speech. This was the star comic’s feature of the evening: a burlesque lecture, delivered in heavy dialect, on a topic of the day such as temperance or women’s rights.

Finally the curtain opened on the setting for the third part of the show, the Afterpiece and Walkaround. Afterpieces began in the late 1840s as sentimental playlets about life on the plantation, but by the mid-1850s they had turned into sharp-edged skits poking crude fun at serious drama. (One was called Medea, or a Cup of Cold Pizen.) The conclusion of the show was the Walkaround, a long and elaborately choreographed number that brought the comedians back for one more antic and ended with a strutting parade around the stage by everyone. It was for the Walkaround that Christy had wanted “Oh, Susanna.” Another popular Walkaround tune was Dan Emmett’s “Dixie,” written for Bryant’s Minstrels in 1860.

For all its foolishness and the slander of its subjects, the minstrel system of producing, promoting, and booking companies marks the beginning of American show business. The conventions of minstrelsy were tried and proven over many years, so they were ready and waiting for the first free blacks who wanted to be entertainers. Their stage was set. Their stories were written. Their characterizations, costumes, and makeup were laid out. To be in show business, all they had to do was put them on.

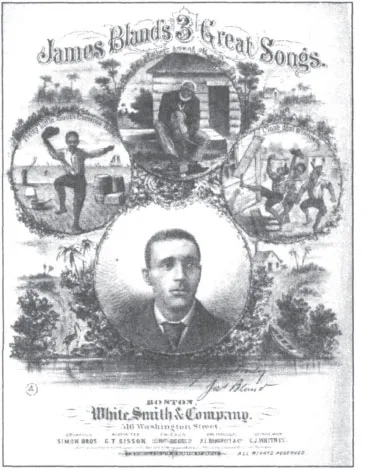

James A. Bland

James A. Bland was neither the first nor the biggest of the African-American minstrel stars, but among the hundreds of black minstrels, his name is the only one recognized today. He alone left a body of work that still matters. His small number of copyrights seems to indicate that he thought of himself mainly as a performer rather than as a songwriter, but a handful of his songs were so good that they have survived by a hundred years the institution that they were written for. There are too many parallels for his career not to be compared to Stephen Foster’s: middle-class childhood, early infatuation with minstrel shows, success at writing for them, carelessness with money, a pauper’s death. The idea of his being “the black Stephen Foster” was prevalent in Bland’s own lifetime and must have rankled him, but the point of the comparison, then as now, is that, between them, they wrote the best songs of the minstrel era.

James A. Bland was born on October 22, 1854, in Flushing, Long Island, New York. He was the descendant of freemen on both sides of his family, his father’s from South Carolina and his mother’s from Delaware. His father Allen was one of the first college-educated blacks in the United States, having received a degree from Wilberforce University in Ohio. Shortly after the Civil War, when James was in his early teens, Allen Bland was offered an appointment as an examiner at the U.S. Patent Office. He accepted the position, and the Blands moved to Washington, where they found a comfortable house at Fifteenth and L streets.

While still a public school student, James took up the banjo and began to play at school functions and parties. After graduation, with music already a rival to his studies, he dutifully enrolled at Howard University. (His father enrolled at the same time and eventually completed a law degree.) During his time at Howard, James noticed the singing of the ex-slaves who were working as groundskeepers, and he tried to compose songs like those he heard.

Bland was a fixture at campus parties. Handsome and gregarious, he was always on hand with his banjo to sing a few of his “refined” songs. Howard was a strict school, requiring uniforms for its students along with mandatory attendance at daily roll calls and drills. Attending entertainments of any kind was strictly forbidden. It was a sign that music was winnin...