![]()

So what is 3D? The term has become a bit muddled lately with the rise of stereoscopic movies, TV, and games that have been termed “3D.” For our purpose, 3D will be the process of creating forms that exist digitally in three dimensions that can then be animated and rendered from any direction.

But even in this more narrow definition, 3D can mean several things that have different goals and different technical benefits or limitations. We will generally lump them into two areas — high rez and low rez (short for high and low resolution).

High-Rez 3D

High-rez animation refers to the amount of polygons and the size of the textures used to describe the surface attributes of those polygons. The medium that high rez is usually delivered through is either film or TV. Because both of these formats are linear forms of motion pictures, what we are really talking about are many pre-rendered frames that are played in rapid succession to create the illusion of movement. Because the frames are pre-rendered (all the information of the model is assembled and “drawn” by the computer), the fidelity of the assets rendered can be incredibly high. And in fact, in cases like film (and increasingly with TV with the rise of HD), the amount of information needed to hold up on the big screen or on high-resolution TV is pretty immense. There’s little room for pixilated textures or renders.

All this information is beautiful but also intensive to work with and costly to render. It’s not unusual to have a single frame of high-rez animation take many minutes or even hours to render. When film is running at 24 frames per second, an intensive render of an hour per frame can mean that it takes an entire day for 1 second of finished animation. Now generally, rendering times are carefully monitored by studios where time is really money, and individual frames are broken up into layers that allow for quite a bit of flexibility and quicker rendering times. But in any case, rendering times of even minutes a frame means that either a studio has a rendering farm of machines to do that work or there is time when just the computer has to do its work.

High-rez work is fun to do because the final product has a great deal of polish, and each frame can be carefully crafted and tweaked. In this book, we will do some high-rez work as it allows (and requires) for some special considerations in the construction of forms and textures.

Low-Rez 3D

Low-rez 3D are assets that computers can draw more quickly. The broadest and well-known instance of low-rez animation is in games. While high rez can take hours to render a single frame, games have to render at least 30 frames every single second. Tons of polygons or textures that are really huge may be beautiful, but a data set that big simply cannot be drawn fast enough by the hardware of today to make the game interactive.

Games work at a higher frame rate by using a very careful polygon count. Forms tend to be blockier as there is less information describing the form. Textures are smaller and always at a “power of two” size (much more on this). Everything that can be done to help hardware draw faster is incorporated to ensure a smooth experience for the player.

This sort of efficiency can be a formidable challenge and takes some careful consideration throughout the creation process. In this book, we will be doing some low-rez work (both a game level and a game character) that will illustrate these ideas. Fortunately, because the amount of data is lower, it’s often times a great way to get started in 3D as the tool set is slightly narrower and the amount of manipulatable data is more manageable.

Now as the technology has increased, the gap between low rez and high rez has been closed. Sometimes, at first glance, it can even be hard to see the difference in low- and high-rez assets; but as you learn more about the 3D process, it will become more and more clear which is which.

The important thing is to know what is being created. Some assets may be reusable between high-rez and low-rez projects — but this is seldom the case. Know from the beginning if you’re building a game or building a movie as it will control many choices in the hours, days, and years to come on the project.

Workflow

Regardless of whether someone is creating low- or high-rez animation, the term “animation workflow” is a bit deceptive. It tends to imply that there is a linear progression in the process of creating animation. In reality, animation of all types tends to be a cyclical process of creating assets, reviewing, recreating assets, reviewing, refining assets, and so on. Perhaps the only two parts of the workflow that really do reliably happen in order is that the animation starts with a sketch and ends with rendering.

However, describing that animation process as “just a bunch of things that happen” is fairly unfulfilling — and is pretty tough for the beginner to grasp. Further, it is true that very broadly speaking, some things do happen before others (a model must be created before its UVs can be laid out for instance). With this in mind, we can start to visualize how projects come together by linearly defining the process. However, as we work through these steps, keep in mind that it’s a very broadly painted image and that there will undoubtedly be some fluidity of order in the process.

An Idea, a Sketch, Lots of Research, and New Inspiration

There is this myth that sometimes floats around the uninitiated that great 3D happens when someone knows 3D software well enough and suddenly the brilliance just flows out of the computer. The reality is very, very far from this. Great 3D animation almost always begins on a paper — drawn with good old traditional media of pencil, charcoal, or paints. No doubt, the final rendered digital output must pass through a computer before its final output — but there is no technical expertise that can compensate for poorly conceptualized or poorly designed projects.

This is why when students contact me before starting our program here at the University of the Incarnate Word and ask what software they should be working on — I always tell them to put the computer down and draw. It is true that there are some 3D artists who cannot draw but can create effective or accurate 3D forms; but generally, if an artist can’t understand a form on paper, they can’t understand it digitally.

Of course, this does not mean that 3D folks are all Leonardo protégés; and usually a good sketch artist is about all that can be expected. But drawing and sketching develops an eye to proportion, anatomy, understanding lighting, and form development.

On the business side, 3D production is time intensive and thus costly. It is much cheaper to approve the 12th sketch of a character or game level than it is to approve the 12th digital model created.

Thus, the first step of most animation projects is planning in the form of drawings. These drawings can be maps of game levels, character style sheets, character pose studies, story boards, set designs, mood renderings, etc. Sometimes these sketches are simply out of the imagination of the artist, director, or other mastermind of a project; but sometime along the line, the critical stage of research must be taken.

Research

As part of the myth that floats around, that computers create great 3D animation (rather than great artists using computers to create great animation), is the idea that designers just sit down and great stuff just appears in their sketchbooks (or designs). In reality, great designs — whether they are game levels, movie characters, or stunning visual matte paintings — are born of research, lots and lots of research.

Here at the University of the Incarnate Word (where I teach), before students begin putting any polygons together digitally, they assemble mounds of research that helps inform their design choices. This doesn’t mean that designs are simply copies of other real-world environments or people, but they make sure that the designer remembers that usually doors have frames around them, the bottoms of walls have floor boards, that breast tissue starts at the collar bone and wraps around the side of the rib cage, and that ears do not have a ledge on their front. Research helps a 3D genius to understand the cut of World War II Nazi criminals, and see the stylized muscles present in comic book heroes and how the proportions are tweaked to create epic heroes.

Take a look at any online gallery of 3D work, and there is almost always a clear dividing line of relevant detail that is missing by those who have failed to do their research. Good research doesn’t guarantee good projects — but will certainly provide the visual building blocks to make sure that the 3D projects have a plausibility that the viewer will accept.

As you can see, I’m a big fan of proper research and doing the hard conceptual work on paper before working digitally. There is simply no “Make Great Animation” pull-down menu. There are rarely happy accidents in 3D; every frame is a hard fought battle and is the result of many choices made along production pathways that culminate in the finished, rendered frame. Ensuring that options have been explored quickly through sketches that are informed by good research will make sure that the production choices yield a product worthy of the blood, sweat, and tears poured into that frame.

Modeling

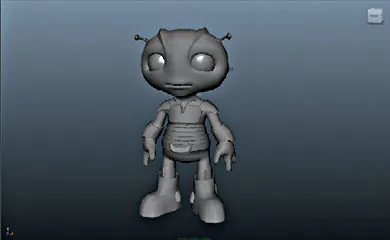

So assuming that the designer (which may be you) has done due diligence in researching and designing their space or character, the time comes that the first asset must be created digitally. Usually, this happens through modeling: the process of assembling the building blocks of 3D forms (called polygons) into shapes that define volume and shape (Fig. 1.1).

FIG 1.1 Results of the modeling process. Form is defined, but everything is gray plastic.

Maya is not actually the most amazing modeling package. To be sure, it is sufficient and has become very good in recent years in adapting techniques and tools that are seen in other packages. But to be honest, it’s not my favorite — especially when high accuracy (like architectural visualization) is required.

However, the other benefits of Maya make the modeling shortfalls worth working around, and keeping the entire workflow within one package is a great way to begin work, so we will be modeling a game level, game character, and high poly bust using Maya’s modeling ...