1 INTRODUCTION: Rome and Carthage1

Carthage was probably founded at some point in the late ninth century BC,2 as a trading colony established by the Phoenician city of Tyre. She maintained close links with her mother-city, but eventually outgrew her, and by 264, more than half a century after Tyre’s destruction at the hands of Alexander the Great, Carthage was the greatest power in the western Mediterranean. Her wealth was proverbial, with Polybius claiming that Carthage was the richest city in the Mediterranean world even when she fell in 146, despite the fact that this was long after she was deprived of her overseas territories (Polyb. 18.35.9).

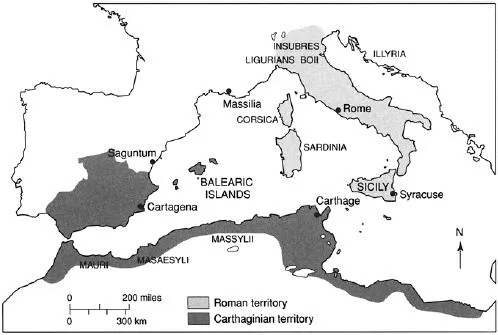

Such territories had been extensive. As a primarily commercial city, Carthage had close connections with the older Phoenician colonies in Spain, cities such as Gades, Malaga, Abdera, and Sexi. A Phoenician colony on the island of Ibiza may have been originally Carthaginian, but even if not, was clearly within Carthage’s sphere of influence by the fifth century, as were the other Balearic islands and the island of Malta. Phoenician colonies had long existed in Sardinia, and by the late sixth century the island was to have been largely under Carthaginian influence. Carthaginian expansion in Sicily had brought her into conflict with the western Greeks, who decisively defeated a Carthaginian army at Himera in 480. Despite this setback, Carthage did not give up, so the Greeks continued to fight under such men as Timoleon, who was victorious at the river Crimesus in 341, and Agathocles, who led an invasion of Africa in 310. Agathocles’ invasion was initially successful, but he failed to take Carthage itself, and eventually returned to Syracuse. By 277 Carthage had lost virtually all of Sicily aside from Lilybaeum to Pyrrhus of Epirus, but her position improved rapidly after his departure and by the outbreak of the First Punic War in 264 Carthage dominated western and southern Sicily. In addition to her overseas territories Carthage controlled the coast of North Africa from Cyrenaica to the Atlantic, past the Pillars of Hercules, founding colonies of her own or taking over other Phoenician settlements such as Utica and Hadrumentum. This network of colonies gave Carthage a virtual monopoly over trade routes in the western Mediterranean, effectively turning the area into a Carthaginian lake.

Apart from the coastal colonies, Carthage had a substantial influence on the interior of northern Africa. Alliances existed with the various Numidian and Moorish tribes who lived in what are now Algeria and Morocco; the Numidian and Moorish rulers appear to have been client kings, who were obliged to send troops to fight in Carthage’s armies. From the fifth century, shortly after her defeat at Himera, Carthage expanded southwards, eventually conquering about half of what is now Tunisia. The highly fertile land thus acquired, coupled with scientific farming techniques, brought Carthage a vast amount of agricultural wealth. Large country estates belonging to Carthaginian aristocrats occupied the city’s immediate hinterland, while land further south was worked by the indigenous population, known as Libyans. They were obliged to serve in Carthage’s armies, and perhaps a quarter of the grain they grew went to Carthage as tribute.3

Carthage was essentially ruled by an oligarchy based on wealth, although it had what was known to ancient writers on politics as a ‘mixed constitution’, one involving elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. Carthage had originally had kings of some sort, but by the time of the Punic Wars the ‘monarchic’ element in the state was represented by the two suffetes, the most powerful officials, who were elected on an annual basis. These supreme magistrates had civil, judicial, and religious roles, but lacked a military function, a highly unusual situation in antiquity. Most administrative decisions were made by a council of several hundred notables, each of whom was appointed for life; the procedure for their appointment is unknown. Thirty councillors formed an inner council, the precise function of which is uncertain, although it is likely that they prepared business for the larger body, making them highly influential. Another important instrument of the state was the ‘Hundred’, a court of 104 judges chosen from the main council. The court’s function was to control the magistrates, especially the generals, who would have to answer for their actions during their time in office. Wealth, as well as merit, was required for appointment to any public office in Carthage, and it appears that bribery was commonplace (Polyb. 6.56.1–4). Finally, the popular assembly was theoretically supreme, and Polybius records that its power grew over time (Polyb. 6.51.3–8). The real extent of its powers is uncertain, however, and it seems that a small number of families dominated both the council and the important magistracies.

Rome was traditionally thought to have been founded in 753, becoming a republic in 509. Like Carthage, Rome also had a ‘mixed constitution’ but was in practice an oligarchy, timocratic rather than plutocratic in character; what counted was military glory, not commercial success. The ‘monarchic’ element in the state was provided by the two annually elected consuls; these were the most important magistrates, whose chief function was to lead the state in war. Other magistrates included praetors, quaestors, and aediles. All these offices were filled by annual elections. The senate was the state’s ‘aristocratic’ element, comprising about 300 former magistrates. Technically, the senate was only an advisory body, but in practice it tended to control Roman foreign policy, receiving and sending embassies, and advising the magistrates, to whom it also allocated tasks and resources. The senate’s decrees did not have the force of law, and had to be ratified by the people, who could meet in assemblies, the ‘democratic’ element in Rome’s constitution. These assemblies were not forums for discussion, but merely voted on proposals. The three main assemblies were the comitia centuriata, the comitia tributa, and the concilium plebis. The wealthier citizens held sway in all three assemblies, especially the comitia centuriata, which elected the senior magistrates and could vote to declare war or accept peace.

Rome was ruled by Etruscan monarchs prior to the foundation of the Republic, and had consequently had good relations with Carthage, since both the Etruscans and the Carthaginians were opposed to the western Greeks. These good relations were evidently maintained, as Polybius records three treaties between Rome and Carthage (Polyb. 3.22–6), the first being negotiated in the first year of the Republic, which he dates to 507; this may have in fact been a renewal of a treaty originally conducted between Carthage and regal Rome. Under the terms of this treaty Rome and Carthage swore to remain friends and not to act against each other’s interests. Rome’s interests were clearly territorial, as Carthage was barred from interfering in Latium, while Carthage’s interests were primarily commercial, with Roman trade in Libya and Sardinia being strictly regulated. A second treaty is of uncertain date, but probably dates to 348.4 This imposed stricter limits on Roman trade with Africa, requiring it to be channelled through Carthage itself, as well as blocking Roman commercial access to Spain. At the same time, it recognised Roman control in Latium, and also seemed to envisage the possibility of Romans plundering and colonising overseas.

This second treaty may have been renewed, or at least informally reaffirmed, in 343, since Livy records that in that year the Carthaginians congratulated the Romans on their victory over the Samnites, and offered a gold crown to Capitoline Jupiter (Liv. 7.38.2). Both states were soon to survive major challenges, with Carthaginian expansion in Sicily being halted by Timoleon at the river Crimesus, while Rome’s allies revolted in 341. The Romano-Latin War resulted in the settlement of 338, under which Rome would henceforth have separate alliances with each individual community, rather than dealing with leagues or confederations. Each community had a clear legal relationship with Rome, and was obliged to send troops to serve in Rome’s armies. This settlement provided the pattern for Rome’s conquest of the rest of Italy, and can rightly be regarded as one of the major turning points of Roman history.

The Second Samnite War broke out in 328, and over the following half-century Roman power spread with phenomenal speed. Constant campaigning on an almost annual basis brought Rome victory over Samnites, Etruscans, and Celts, giving her control of much of the Italian peninsula. Livy claims that Rome and Carthage conducted another treaty in 306 (Liv. 9.43.26). Polybius mentions no such treaty, although he goes to great pains to deny the existence of a treaty recorded by the Sicilian historian Philinus, which recognised Italy and Sicily as respectively Roman and Carthaginian spheres of influence (Polyb. 3.26). If Polybius was mistaken and the so-called ‘Philinus treaty’ was genuine, it may well correspond to Livy’s treaty of 306.5

Thurii and other Greek cities in southern Italy appealed to Rome for help against the depredations of their Lucanian neighbours, but Roman involvement in Greek Italy was opposed by Tarentum, the most powerful of the Greek cities there. In 282 the Tarentines attacked a squadron of Roman ships, and cast out the Roman garrison at Thurii, replacing its oligarchic government with a democratic one. Rome understandably declared war, and the Tarentines, realising that they could hardly resist Rome without help, turned to Pyrrhus of Epirus, the powerful Greek monarch. It appears that Pyrrhus was only too glad of the opportunity to build a new empire in the west, an empire that would include not merely Italy, but also Sicily and Carthage, if Plutarch is to be believed (Plut., Vit. Pyrrh. 14.3–5). He arrived in Italy in 280, leading an army of over 25,000 men and twenty war elephants, counting on the support of the western Greeks as well as that of the Samnites, Lucanians, Bruttians, and Messapians. Pyrrhus was twice victorious over the Romans at the battles of Heraclea and Ausculum, but he suffered enormous losses which he could ill afford. None of Rome’s allies defected to him, and Rome fought on, refusing to negotiate while he was still on Italian soil, ignoring the unwritten conventions of Hellenistic warfare by not suing for peace despite having been beaten. Realising that the war in Italy was a lost cause, Pyrrhus answered Syracuse’s appeal for help against Carthage, and set out for Sicily.

At some point while Pyrrhus was in Italy, probably just after his victory at Ausculum, the Carthaginian admiral Mago arrived at the Tiber with a fleet of 120 ships, offering assistance (Justin 18.2). It was most likely at this point that Rome and Carthage negotiated another treaty. This confirmed previous agreements and added that should either state conduct an alliance with Pyrrhus, it would do so with the proviso that it would be permitted to go to the assistance of the other should it be attacked; in such an eventuality the Carthaginians would provide ships for transport or war (Polyb. 3.25.2–5) (see Walbank, 1957, pp. 349–52). The treaty did not oblige Rome to come to Carthage’s assistance in Sicily, it merely permitted it. Pyrrhus was initially very successful against Carthage in Sicily, but failed to take Lilybaeum, and in late 276 he returned to Italy, losing a sea battle to the Carthaginians on the way. Following a defeat at Malventum, the future Beneventum, he lost heart, withdrawing to Tarentum and sailing back to Greece.

When he left Sicily Pyrrhus is reputed to have declared ‘what a wrestling ground we are leaving behind us for the Romans and the Carthaginians’ (Plut., Vit. Pyrrh. 23.8). Such a remark, if true, was to prove prophetic. Rome continued the war against the western Greeks after Pyrrhus’ departure from Italy, eventually compelling Tarentum to surrender. However, while the Romans were besieging the city in 272 an ominous event occurred: a Carthaginian fleet appeared in Tarentum’s harbour. The Romans protested, and the Carthaginians claimed that the fleet had actually only come to offer assistance to the Romans in accordance with the terms of their recent treaty. Nevertheless, this event must have provoked much suspicion in Rome (Lazenby, 1996a, pp. 34–5). In Pyrrhus’ absence the Carthaginians had an almost entirely free hand in Sicily, being opposed only by Hiero of Syracuse. Messana, opposite Rhegium on the Straits of Messina, had been occupied by a group of Campanian mercenaries called ‘Mamertines’ since 288; these came into conflict with the Syracusans, who defeated the Mamertines in battle at the river Longanus (Polyb. 1.9–7–8). Realising the weakness of their position, the Mamertines appealed to both Rome and Carthage for help (Polyb. 1.10.1–2). The Carthaginians were the first to respond, sending a garrison to protect the town.

In an unprecedented move, Rome also responded to the Mamertine appeal, sending troops outside the Italian peninsula for the first time in their history. Such an action, which was in contravention of the ‘Philinus treaty’, assuming that the treaty actually existed, was bound to bring Rome into conflict with Carthage. The reasons for Rome’s decision are unclear, but the strategic value of Messana must have been obvious. Control of Messana could have enabled Carthage to take control of all Sicily, and Messana itself was perilously close—only 10 miles —from Roman Rhegium. The senate was split on the issue so the matter was taken to the people. Perhaps driven by that desire for military glory which was the hallmark of Rome’s aristocrats, the consuls advocated alliance with Messana, tempting the people with the prospect of plunder in the subsequent war; the people agreed, and appointed Appius Claudius Caudex, one of the consuls, to the Sicilian command (Polyb. 1.10.3–11.3) (Lazenby, 1996a, pp. 37–41; Walbank, 1957, pp. 57–61; Scullard, 1989a, pp. 539–43; Harris, 1979, pp. 182–90).

The Mamertines expelled their Carthaginian garrison, and invited the Romans into the city. The Carthaginian officer was then executed by his own men, and the Carthaginians made a fresh and highly unlikely alliance with the Syracusans, with the aim of driving the Mamertines, and by implication the Romans, from Sicily. The Carthaginians sent troops to garrison Agrigentum and lay siege to Messana, near where the Syracusans were also encamped. Claudius was nevertheless able to transport his army across the Straits of Messina, and then sent embassies to Hiero and to Hanno, the Carthaginian commander, demanding that they lift their siege of a city which was allied to Rome. They refused, and war was declared. The First Punic War lasted for twenty-three years, from 264 to 241, and was probably the longest continuous war in ancient history.

Hiero soon switched sides, and henceforth proved a loyal ally of Rome. Agrigentum was besieged for seven months in 262, but although the town fell to the Romans the Carthaginian commander and most of his men escaped. Several other Carthaginian-controlled towns defected to Rome, and Carthage instead decided to fortify several points in Sicily and, while holding these, to harry the Roman supply lines in Sicily and use their naval supremacy to plunder the Italian coast. In order to deal with this the Romans quickly expanded their navy, building twenty triremes and 100 quinqueremes, and equipping these ships with a strange device called a corvus, or ‘crow’. This was a boarding-bridge with a hook on one end which could be dropped onto the deck of a hostile ship, pinning it into position and allowing Roman troops to board it. After an impressive naval victory off Mylae in 260, Rome mounted small-scale expeditions with some success to Corsica and Sardinia, and in 256 achieved another immense naval victory at Cape Ecnomus. This cleared the way for the launching of an invasion of Africa, which was initially very successful, until one of the consuls, Lucius Manlius Vulso, was withdrawn, leaving Marcus Atilius Regulus in command of a reduced army. The following year Regulus was defeated by a Carthaginian army commanded by a Spartan-trained mercenary called Xanthippus. In 254 the Romans were again victorious at sea, but most of their fleet was soon destroyed in a storm off Camerina, with further disasters in subsequent years. On land, the fortunes of both sides varied. The Romans captured Carthaginian Palermo in 254, but failed to take their stronghold at Lilybaeum. Hamilcar Barca, a young Carthaginian general, was sent to help Himilco defend Lilybaeum in 247 or 246. He based himself on Mount Eryx, raiding the Italian coast as far north as Cumae and harassing the Romans in Sicily itself. Rome raised another fleet which attempted to blockade the Carthaginians in Lilybaeum and Drepanum, and when a Carthaginian fleet arrived it was decisively defeated at the Aegates islands. Hamilcar was instructed to negotiate a peace treaty with Rome.

This treaty dictated that the Carthaginians evacuate Sicily and not attack Syracuse. All prisoners of war were to be returned, and Carthage would have to pay war reparations of 2,200 talents of silver over twenty years (Polyb. 1.62.8–9). However, when these terms were put before the Roman people they were rejected, and so a ten-man commission modified the treaty, making it much harsher: they demanded war reparations of 3,200 talents of silver, to be repaid over only ten years, and insisted that Carthage also evacuate all islands between Sicily and Italy (Polyb. 1.63.1–3).

Carthage’s woes were far from over, as an army of about 20,000 mercenaries, which she could not afford to pay, rose against her and based themselves at Tunis. Their numbers were soon swollen by the subject Libyans, glad of a chance to try to shake off the Carthaginian yoke. Carthage was cut off from its territory, with rebel armies besieging Utica and Hippo. Hanno failed to relieve Utica, and was replaced by Hamilcar Barca, who defeated the insurgents at the battle of the Bagradas. He destroyed another insurgent army at a spot called the Gorge of the Saw, and the rebels were again defeated decisively in 237. After this, the occupied Hippo and Utica quickly surrendered to Hanno and Hamilcar. This ‘Truceless War’ had been a real life-or-death struggle for Carthage, and was notable for the remarkable cruelty with which it was conducted on both sides.

Unfortunately for Carthage, her mercenaries in Sardinia had also revolted. Rome behaved impeccably towards Carthage during the war, and refused to accept the insurgents as allies, despite appeals from the mercenaries in Sardinia and Utica. However, the native Sardinians managed to expel the mercenaries, who again asked Rome for help. Despite Carthaginian protests, the Romans proceeded to occupy the island. They threatened Carthage with a renewed war, and when Carthage submitted, a further 1,200 talents were added to the reparations she was to pay Rome (Polyb. 1.88.8–12). Carthage may not have fought to keep the Romans out of Sardinia, but the island’s inhabitants did not submit so readily, and Rome appears to have campaigned constantly in Sardinia and Corsica up to 231, at which point she turned her interests further east, to the Celts of Cisalpine Gaul and to Illyria (Harris, 1979, pp. 190–200).

Map 1 The Western Mediterranean at the outbreak of the Second Punic War.