![]()

Part I

Contexts

![]()

Chapter 1:

History

1869–1943

Italian colonialism was an entirely political phenomenon … [it] produced prestige, but never power.1

Giorgio Rochat, 1992

Imperialism,2 as practiced by late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europeans, was haphazard, careless, and poorly directed. The good and bad effects were more the result of accident than of calculation. Few administrators were well-trained to cope with modernity; few were even interested in it.3

Raymond Betts, 1985

The progress of the arts during the Fascist period – when Italian architects theorized colonial architecture and Italians built a great deal in the colonies – is easily recapitulated. The years between the early 1920s and the mid-1930s were characterized by relative artistic freedom, experimentation, and open debate. The period that followed was marked, instead, by increasing artistic and architectural uniformity, subservience to the government’s totalitarianism, and a dying-out of artistic debates. Similarly, the trajectory of Italian colonial architecture follows a simple timeline: prior to the 1920s – i.e. for the first decades of Italian colonial expansion – architecture played hardly any part in Italians’ views of the colonies. They did not discuss how they should represent themselves there through their buildings, or the worth of local architectures. In the second half of the 1920s, architects began to write about “colonial architecture” as a new object to be defined and to be shaped actively, in response to national and colonial agendas. By the first half of the 1930s, colonial architecture had a significant place in architectural journals, conferences, and exhibitions. But after the mid-1930s – as with the other arts in the late Fascist period – debates on colonial architecture died down, and the practice of colonial architecture and city planning fell under a blanket of unquestioning uniformity. In Chapters 3 through 5, I describe these three periods as the pre-architecturalist, the architecturalist, and the uniformalist.

Before analyzing the gradual application of Italian architectural debates to colonial settings, however, I provide a brief history of Italian colonialism in this chapter and analyze the symbolic underpinnings of Italian colonialist ventures in the next. The twists and turns of Italian colonial-architectural discourses and practices accompanied those of politicians’ positions and popular images of the colonial exotic; thus these first two chapters set the stage and provide the context for my analyses of Italian colonial architecture, as they did for the architects themselves. In this brief sketch, I highlight five thresholds; crucial moments of directional change in Italian imperialism: 1881, 1896, 1911, 1922, and 1936.4

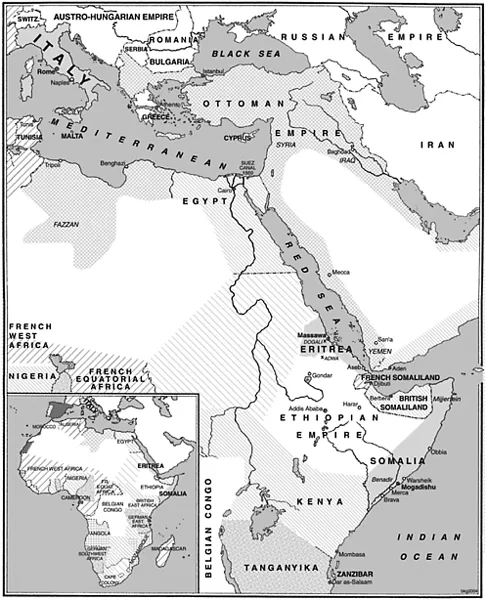

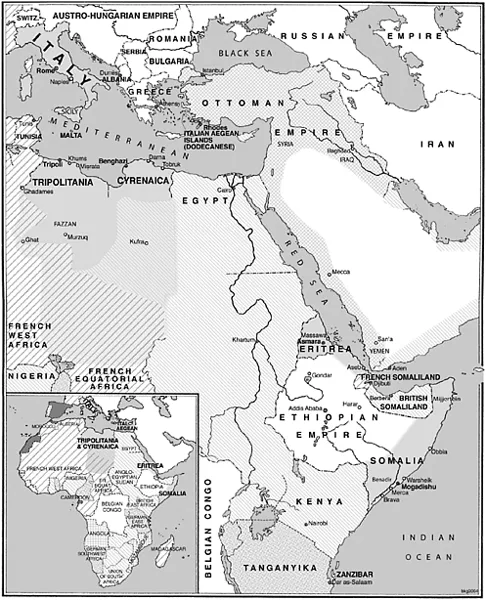

The Italian acquisition of Red Sea territories, beginning in 1869, was desultory until France’s 1881 occupation of Tunisia – which Italians had expected to colonize – provoked them to pursue colonialism more aggressively. Fifteen years later, the crushing 1896 defeat of Italian troops at Adwa (Ethiopia) brought Italian colonial ambitions to a temporary halt (Figure 1.1). Beginning in 1911, Italy’s occupation of Tripoli assuaged some of the disappointment over the “loss” of neighboring Tunisia, and inaugurated a new era of Italian colonial optimism (Figure 1.2). The Fascist takeover of the Italian government in 1922 brought more systematic aggression to the colonies, and increasing uniformity in colonial administration. Finally, the occupation of Ethiopia in 1936 (acclaimed as a long-awaited revenge for the losses at Adwa) heralded a new imperialist stance on the part of Italians, reflected in newly prominent notions of racial superiority and plans for residential and social segregation between Italians and Africans (Figure 1.3).

THE BEGINNINGS OF ITALIAN COLONIALISM: FROM ASEB TO ADWA, 1869–1896

Italian colonialism began with a single capital investment. In 1869, the inaugural year of the Suez Canal and a mere eight years after Italian national unification, the Rubattino shipping company independently purchased rights over a six-kilometer stretch of land at the Red Sea port of Aseb from local sultans.5 The company’s agent, Giuseppe Sapeto, hoped to draw the Italian government into a colonial role. By the late 1930s, the government would be the principal economic support for all of the Italian colonies (not one of which would ever become self-sufficient);6 but in these early years, the government hesitated to invest, and turned repeatedly to privately owned companies for the exploration, financing, and management of colonial territories. A decade passed before Sapeto persuaded the state to endorse his colonial acquisition, and a few more years passed before the government sent military forces to occupy Aseb in 1882 – the year after French troops took hold of Tunis, and the same year British forces occupied Egypt.

Italian expansionists had felt that Tunisia, once it was wrested from Ottoman control, was due to Italy more or less by rights because of its geographical proximity to Italy, and because a large Italian population lived there.

Informally, some Italians held that it was already part of Italy: “in reality, Tunisia is a small, African Sicily.”7 Colony-minded Italians had tacitly assumed that this expectation would be respected by other European nations, and saw the French government as having betrayed them. Combined with the ongoing British expansion, the French protectorate over Tunisia gave Italian politicians a new sense of urgency and drove them to advocate their cause with greater vigor than before. The government quickly followed its occupation of Aseb with the declaration that it was an Italian protectorate. Official government support of Italy’s colonial options continued to develop through the 1880s until 1896, based in part on information gained from growing numbers of scientific expeditions by explorers and geographic societies. The state was interested in two regions, albeit unequally: primarily the Mediterranean, and secondarily the Red Sea and Indian Ocean coasts on the Horn of Africa.

In 1885, the government occupied the Egyptian-controlled Massawa, another Red Sea port, with the support of the British, and declared it a protectorate as well. Its strategy was to gain control along the coast and check the progress of other European powers in the Red Sea; in addition, it hoped to move troops into Ethiopia (also called Abyssinia 8). Ethiopia, then under the rule of Emperor Yohannes IV (1831–1889), was itself in a process of rapid territorial expansion, which would continue under Emperor Menelik II from 1889 to 1913. Ethiopian forces staved off Italian encroachments for the time being, most notably by defeating roughly 500 Italian soldiers in 1887 at Dogali, in the lowlands near the Red Sea. Later that year, Francesco Crispi, one of the most important statesmen of Liberal Italy, became both Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs and his administration continued to support expansion along the Red Sea. In 1889, Menelik II and an Italian representative signed a treaty allowing further Italian occupation of the Red Sea coast, and Italian forces went on to occupy the nearby highlands. In 1890 the government consolidated its Red Sea possessions into Italy’s first colony; Crispi named it “Eritrea” because the name evoked the classical Greek term for the Red Sea.

Italian involvement in the Benadir region of southern Somalia also began in the 1880s. In 1885, the Sultan of Zanzibar and the Italian explorer Antonio Cecchi, acting on behalf of his government, forged a commercial agreement giving Italians access to the coastal cities (Brava, Merca, Mogadishu, and Warsheik). The Sultans of Obbia and Mijjertein controlled the northern part of the Indian Ocean coast, and the Italian government negotiated protectorate arrangements with each of them four years later, in late 1888 and 1889. It then occupied the Benadir in 1891, by placing askari (native soldiers – from Eritrea, in this case) in the coast’s first permanent Italian military establishment.9 Hoping for indirect rule, the government delegated local administration to an Italian merchant, Vincenzo Filonardi, in 1893, in return for the commercial concession and a subsidy.

In Eritrea, in contrast, Italian politicians hoped to settle great numbers of Italians on farmland through programs of “demographic colonization”; in theory, this would stem some of the tide of Italian emigration to the Americas and elsewhere, as well as urban growth in the metropole, by attracting Italian manpower to the new territory.10 The government always intended Eritrea to be a settlement colony, and indirect rule was never attempted there.11 Vast areas of the highlands were expropriated for settlements but, by 1894, local resistance to these expropriations crystallized in an uprising led by the chieftain Bahta Hagos; Italian occupying forces responded by destroying villages, massacring inhabitants, and deporting prisoners to Italy. Italian troops also moved further into the Ethiopian highlands, eventually entering the battle of Adwa – the second of our chronological thresholds – in which they were crushed by the Ethiopians in March 1896. European troops had been defeated by African ones before, but this was the worst such defeat to date. (Estimates vary, but Italian and askari casualties probably totaled between 4,000 and 7,000.) Italian aspirations to expansion crumbled under the ridicule of what many Italians perceived as the most ignominious loss imaginable. Up to this point, Crispi had been the most resilient politician in Italy since the country’s political unification, but the loss of face from Adwa was so irreparable that it brought down his last government.

AFTER ITALY’S DEFEAT AT ADWA

In the wake of this national disaster, politicians were reluctant to pursue Italian expansion any further. In late 1896, the government signed a treaty with the Emperor abandoning any designs on Ethiopia. Eritrea was assigned its first civilian governor, Ferdinando Martini, in 1897, when the colony was commonly judged to be a failure due to its poor agricultural results and high cost. Over the decade he served as governor, Martini changed this perception by establishing stable relations with Ethiopia and re-directing Italian goals away from agricultural development by and for Italians toward agricultural exploitation for export.12 The improvement of the Italians’ status in Eritrea paralleled a general upswing in Italian affairs after the turn of the century. Un...