1

Clinical Theories of Loss and Grief

BEVERLEY RAPHAEL, GARRY STEVENS AND JULIE DUNSMORE

The introductory chapter is remarkably comprehensive, covering themes of restoration, intervention, and community support after violent death, and is detailed in clarifying the development of contemporary grief theories — beginning with attachment, normal bereavement, pathologic grief, complicated grief, traumatic bereavement, and finally, violent death and grief. The authors also introduce the dynamic interplay of trauma and separation distress following violent death amplified by authors in later chapters on intervention. The chapter cites sources of vulnerability and resources of resilience after violent death, and closes by developing a clinical protocol brimming with relevant, clinical recommendations, a rich smorgasbord of clinical substance and wisdom.

The loss of a loved one following a violent death is a shocking experience. The loss may be an individual one — for instance when a family member is killed in a violent accident, or a sudden event of nature that takes the lives of many. The latter may not reflect violent intent, but the sudden, unexpected, untimely death, particularly of a young person, may be experienced as "violent." Such events have the power to shock, disrupt, and violently affect the lives of those left behind, of those bereaved. Other deaths may be readily seen through the prism of violence. Homicide is an obvious form of individual and violent death, profoundly affecting the families of those who have died, and indeed, everyone touched by this event. Suicide deaths are also frequently violent, both in their suddenness, but also in the nature of the self-destroying act. With deaths such as these, the most profound bereavement may be experienced by those with intimate attachments, be they partner, spouse, parent, or child, but also across range of other intimate bonds.

Mass violence, involving multiple violent deaths, constitutes another overwhelming loss. The grief and bereavement that follow affect not only surviving family members of those who have died, but also their social networks and wider communities. While this may occur to some degree with the i ndividual incidents noted above, when large numbers die violently the impact is profound, both emotionally and in the breaking up of social networks vital to the community and its recovery. Again, mass deaths may occur through violent natural events, such as the Armenian earthquakes, or the extraordinary circumstances of the Southeast Asian tsunami in 2004. They may take place as a result of mass technological accidents such as a plane crash or building collapse, where elements of human failure or specific negligence may come into question. History has seen mass death through conflict, war, or even genocide and through recent acts of terrorism such as September 11, the bombings in Madrid and London, or the Beslan, Chechnya school siege. These multiple scenarios concerning violent death have implications for the bereavement, for the reactive processes of grieving, and for outcomes. They are also contexts that require careful consideration in terms of the nature of care provided to those bereaved.

There is now burgeoning literature on bereavement with a wide range of theoretical constructs to inform understanding and practice. Given these diverse methodologies, the focus on bereavement through the lens of PTSD, and seminal events such as September 11, it is important to determine some key principles and guidelines that can inform interventions. There is also a need to further explore the opportunities that may exist to prevent adverse mental health and other outcomes associated with such losses.

It is widely acknowledged that grief and bereavement are a normal part of life experience. In Engel's (1961) influential model, for example, grief is not a "disease." Nevertheless the need to delineate and understand these normal phenomena is critical because such phenomena, and their psychophysiolog-ical correlates, can provide a baseline against which changed patterns can be assessed and measured. Key variations, for instance, may indicate pathological processes or be predictive of poorer outcomes. With regard to the specific clinical theories and orientations, Middleton, Moylan, Raphael, Burnett, and Martinek (1993) surveyed the theoretical constructs that informed bereavement research to that time, and found that attachment theory predominated as a conceptual basis. Other models included cognitive, assumptive models, and traumatic stress frameworks. For instance Horowitz (1976) described bereavement as a stressor that could lead to a traumatic stress syndrome.

Social structures and roles are profoundly impacted by bereavement, particularly in the aftermath of violent death, and clinical theories must be informed by these social and systemic dimensions. These events and processes affect the social identities involved, such as moving from identity of wife to that of widow; the possible changes in socioeconomic status; ongoing social and stressor impact of the consequences of the loss of the person; the presence, absence, perceived helpfulness or unhelpfulness of those attempting to comfort, console, or support the bereaved. All of these factors may significantly affect ongoing adaptation. Furthermore, the practices of ritual behaviors prescribed by culture, religion, or society contribute additional processes to be recognized in any systems of response and understanding. Broader community recognition of the loss may also provide a level of support. Alternatively, its absence, its specific form, may constitute a further stressor impact.

What is considered "normal" may be defined not only in psychological, but also in sociocultural terms. For instance although weeping and distress were once considered "unmanly" in some Western cultures, these are psychologically normal processes. Work such as that of Bowlby (1980), Byrne and Raphael (1994), Jacobs (1993), Parkes and Markus (1998), and Middleton,Burnett, Raphael, and Martinek (1996), have shown that common sets of phenomena occur. These include shock, numbness, and disbelief as frequent initial responses; yearning, longing, protest, and searching behaviors; psychological mourning processes that involve preoccupation with images of the deceased and review of the lost relationship; and progressive relinquishment of bonds to the deceased. Associated affects include sadness, anger, guilt, and longing as it is increasingly accepted that the person will not return, that life, which involved this person, is permanently changed. Measures such as the Core Bereavement Items Measure (Burnett, Middleton, Raphael, & Martinek, 1997) and those of Middleton, Burnett, et al. (1996), attempt to identify and track such normal bereavement over time. Numerous other scales and measures have evolved for such purposes. The importance of measures such as the CBI, and also those such as Jacobs, Kasl, Ostfeld, et al. (1986), is that they can be used to track the phenomena as expressed by the bereaved person, rather than the risk factors or pathological items per se, which are also useful factors in themselves. Studies using these measures have shown the progressive attenuation of the acute grieving process in the early months, which occurs for the majority of those bereaved. A similar pattern is also observed regarding ongoing grief during the first year.

The review by Middleton, Moylan, Raphael, Burnett, and Martinek (1993) showed that, at that time, there was little conceptual agreement amongst researchers about the definition or nature of pathological grief, which was also variously called "absent grief" and "delayed grief." There was agreement to a greater degree about longer-term or "chronic grief." Many workers had commented about the overlap of grief and depression, while others had focused on factors that might correlate with poorer health outcomes, as measured a year or more following bereavement. Importantly, researchers began to define diagnostic criteria for pathological, complicated, or other anomalies of grieving. Prigerson et al. (1999) identified important patterns in a model of "complicated grief" for which a specific measure has now come into common use. These phenomena reflect a pattern of heightened anxiety, including separation anxiety, which follows the loss of a highly dependent relationship. These reflected phenomena are similar to those identified by Raphael (1977) and Parkes and Weiss (1983), and which these latter authors found to be predictive of poorer bereavement outcomes. Prigerson's work has been particularly valuable in furthering understanding within the field, notably through her empirically sound studies, use of tools to provide a basis for research, and for the subsequent improvement in the quality of intervention (Gray, Prigerson, & Litz, 2004). This work was somewhat complicated by the fact that for a period of time it was called "traumatic grief," and overlapped with different constructs that will be discussed below. Nevertheless complicated grief is now a central construct guiding work in this field.

Horowitz et al. (1997) developed a similar conceptual framework for complicated grief, which similarly reflected the findings of Prigerson's group, that complicated grief was distinct from depression (Prigerson & Jacobs, 2001; Prigerson, Maciejewski, et al., 1995). Many of the phenomena described as elevated or prolonged with complicated grief were similar to those that were found to persist as potential chronic grief in the work of Byrne and Raphael (1994) and Middleton et al. (1996). These latter studies involving two separate, well-selected community samples both found that approximately 9% had persisting levels of such grief when assessed at follow-up (Raphael & Minkov, 1999).

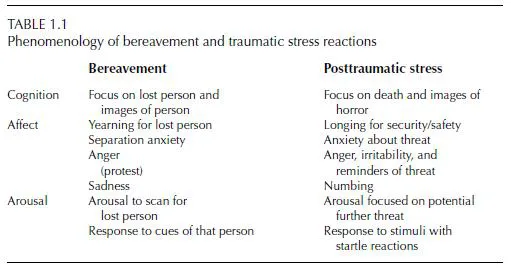

Although the term traumatic bereavements has been widely applied, including to the complicated grief model noted above, it will be used in this chapter to denote the complex interaction that may occur between traumatic stress phenomena and bereavement phenomena. This may particularly arise where the circumstances of the death also evoke personal life threat and confrontation with death in gruesome, mutilating, and horrific forms, as with violent death (Raphael & Martinek, 1997; Raphael, Martinek, & Wooding, 2004; Raphael & Wooding, 2004). The distinct cognitive, affective, and psy-chophysiological aspects of bereavement and posttraumatic phenomena are outlined in Table 1.1. The former are characterized by distress, yearning, and an orientation "toward" the absent person; the latter by heightened fear and arousal, vigilance and a reactive orientation "away from" the feared event or its reminders. This delineation provides a useful basis for clinical assessment and intervention.

More recently there has been work such as that of Katherine Shear, which has emphasized the importance of intervention tailored to meet these specific needs (Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005). These interventions will be discussed further below.

Pynoos also highlighted these separate phenomena and their potential interactions in his work with children (Pynoos, Nader, Frederick, Gonda, & Studer, 1987). He demonstrated traumatic stress reactions following death-threatening exposures, grief reactions following loss, and specific reactions to caregiver separation in children affected by a school sniper attack. More recently Judith Cohen has extended these concepts in her studies of traumatic grief in children (e.g., Cohen, 2004). All these studies highlight that the traumatic circumstances of these deaths is a critical factor affecting outcomes.

An increasing number of studies have tried to conceptualize what happens after violent deaths, even though the impact of violence per se is not consistently and specifically addressed. An exception to this has been Rynearson's work with those bereaved by homicide deaths. His early reports (e.g., Rynearson, 1987; Rynearson & McCreery, 1993) and later therapy models (Rynearson, 2005; Rynearson & Sinnema, 1999) highlighted the particular significance of the violent intent of perpetrators as well as the distressing images of the circumstances of death. As noted above, violence may be associated with both natural events and accidental circumstances. These may lead to traumatic stress as well as bereavement reactions. However, when there is malevolent intent, as with homicide or the mass violence of terrorism, then there are additional stressor impacts to be addressed: those of coming to terms with what others have done to loved ones; that survivors themselves may have felt directly threatened; and that the threat itself may be ongoing or uncertain. These all add an extra dimension of distress. In these circumstances, as Rynearson has discussed, there may also be legal imperatives shaping the environment in which the bereavement continues, and which will bring their own concerns and uncertainties. These may include the Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) process, the medical examiner's requirements, crime scene demands, ongoing investigations, security, and other constraints.

Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Those Bereaved

To deal with grief, to grieve for a loved one, may require certain conditions. Some environmental factors, personal experience, and individual characteristics will make some people vulnerable to difficulties. Other factors in these same domains may contribute to more positive grieving trajectories and outcomes. As noted previously, both practical and emotional support from others through this process may be helpful. For both psychological trauma and grief processes, perceptions of the available support as helpful is associated with better coping and outcomes (Maddison &Walker, 1967; Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe, & Schut, 2001). Past losses may leave some people vulnerable, particularly if the overall impact of disadvantage or loss has left little in the way of family or social networks. Earlier losses, for instance of a parent in childhood, may in some circumstances make attachments less secure, thus making the bereavement more complicated. Specific past trauma, such as child abuse, has also been associated with vulnerabilities affecting the course of bereavement (Silverman, Johnson, & Prigerson, 2001). However, grief and trauma in early life or previously may also have been associated with personal growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995, 2004; Vaillant, 1988) such that the individual may have developed strengths to deal with the circumstances of the death and loss. A preexisting psychiatric disorder may also influence the capacity to handle these major stressors, particularly when they are multiple and combined. Nevertheless, as Bonnano (2004) and others have highlighted, many show great personal strengths in the face of major losses. Other disabilities, such as physical illness and incapacity and other life changes at the time of the death may add substantial stressors that place an extra demand on those attempting to move on from this experience.

Rituals around the traumatic or violent death may significantly affect adjustment. The bereaved may be "blamed" or suffer survivor guilt, blaming themselves. There may be an inability to meet religious requirements, which are important to the ...