![]()

1

C.C.V. – CHIEF CREATIVE VISIONARY

What is an Animation Director?

At family gatherings, church activities or at a party the dreaded question arises after I tell a stranger what I do for a living. “An Animation Director? How do you direct a cartoon?” The alchemy of how animation is made is such a mystery to people outside the entertainment industry that they cannot fathom why an animated project would even require direction. After all, presumably there are no “real actors.” My trite answer: “Well, you know how a live action director oversees the creative process of a film – from script, casting, production design and costumes to developing the scenes, editing, and score? Well, I do all of that, except I do it one frame at a time!” Usually that leaves them with an even more confused look on their faces. In a nutshell, that is one of the reasons I decided to write this book. To help others understand what a director or supervisor in charge of a creative team does to make the magic happen.

“A director must be a policeman, a midwife, a psychoanalyst, a sycophant and a bastard.”

– Billy Wilder

The Love Affair Begins …

“In a galaxy far, far, away …” that’s where it all started for me. We all have those defining moments in our lives where we realize what we want to do in life. I was 10 years old in 1977 when my brother and I rode our bikes to the local theatre and bought our tickets for Star Wars. My mother had seen it already and told us it was too scary for us to see. After a week of hearing gushing reviews from every 10 year old in the neighborhood, we begged our mom on bended knee and she finally conceded to let us go see the movie. By the time the lights came up in the theatre my life was changed. My brother and I talked about Star Wars all the time and created our own stories and characters to help Lucas expand upon the legend (as if he needed our help). That summer we became film buffs and went to the theatre as much as our allowance would allow. The Academy Awards became a staple on our family TV every year and we collected all manner of toys, bed sheets and apparel from whatever new film character craze we were into. I was mesmerized by the magic of movies.

The stars and filmmakers of our first Super 8 movie, Blind Date: Tom and Tony Bancroft. Surprisingly, Tom agreed to wear the dress.

Names like Spielberg and Lucas were regulars in our house. They weren’t actually at our dinner table but they certainly were talked about around it. The 1980s were when directors like Coppola, Spielberg, Lucas and Scorsese became household names. I didn’t fully understand what a director did back then but I knew I wanted to be one. My brother and I dreamed of directing our own movies and by the time we were in college we were shooting our own Super 8mm film productions. We crafted fine cinematic masterpieces such as “Fly Boy” about a boy who wished he could fly like Superman and then does (not a lot of plot development on that one) and “Blind Date” about a boy who has everything go wrong as he is excitedly preparing for his big date to the point that when he shows up at the girl’s door he is a bruised and battered mess with green hair (for some reason that I can’t remember). Of course to his happy surprise, the door swings open to reveal a girl (my brother dressed in drag) who looks exactly like him having gone through all of the same experiences preparing for the evening out. And the list cinematic genius went on from there. But, while the Bancroft Brother’s film library was not long in story development there was no denying – we were making films! My brother and I were the writers, actors, make-up, costumes, special effects department and editors all wrapped up in two scrawny twin teens but more than that we were directors!

Disney directing team: John Musker and Ron Clements.

It was soon after that my brother and I discovered our talent for drawing comic strips could be combined with our love of movies in the form of animation. After some time at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) studying character animation, Tom and I were asked to join the Walt Disney Studios in their Feature Animation division. It was here at Disney that I learned the difference between a live action director and a director on an animated movie. What’s the difference? In short, not much. The live action director is in charge of the story, writers, actors, set designers, costumers, lighting, cinematography, sound effects, music, visual effects, and final color of the film. Basically, all creative elements involved with a movie. The director of an animated feature is involved with all of those elements also but has control of them at 24 frames a second. It’s like directing in slow motion.

Disney directing team: Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise.

At my college, CalArts, there were no courses in directing in the animation department and no discussion about how to become one either. Everything I learned about directing came after working as an animator at Disney on classics such as Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, and The Lion King working under some of the best animation directors in the industry. Ron Clements and John Musker, Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, and Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff (respectively) became my teachers. It was by their example, that I discovered what they don’t teach in art school about directing or supervising a crew could fill a book. This book in fact. Case in point: I was a young first-time supervising animator on The Lion King when my production manager told me that I had to write a review on each animator that I supervised on my team on the character Pumbaa. My review of their work did not stop at my opinion of their artistic merits (did they squash when they were supposed to stretch?) but also their professional behavior, how well they took direction, their time management skills and so on. My review would help determine if my colleagues got considered for promotion, salary raises or worse case, fired. These were managerial pressures I didn’t read about in the animation bible The Illusion of Life. This was real life!

Disney directing team: Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff.

From The Lion King. © 1994 Disney.

While much of my focus on the job of directing will be from the perspective of an animated feature film director, the elements I discuss through the course of this book will also be helpful to the visual effects supervisor, director of animation on a commercial or video game, a director of a television series, or director of a short film. They all have one important thing in common; they all have to share and enforce their vision to a crew of not-so-like-minded artists. The thing that makes directing difficult and wonderful at the same time is working with all of the unique personalities in your creative team AND getting them focused in one direction. There are numerous skill sets that will come into play while directing that go well beyond the obvious artistic principals on cinema taught in school. At some point or another you will be a: coach, cheerleader, politician, negotiator, diplomat, parent, salesman, executive, and servant to your crew. That’s a lot of hats to wear! This directing thing is not for the faint of heart.

In the next several chapters I will explore what it means to be an animation director and helpful hints on playing well with others while creating great art.

Terms and Titles Defined

In the entertainment industry you will come across a lot of different titles for the role you play on a project. When I first started at Disney as a matter of fact, I was an assistant animator but I didn’t assist an animator at all. I was a glorified clean-up artist in a crew of clean-up artists doing the final line drawing on a 2D animated film. Then I was promoted to a beginning animator who worked closely with a senior animator. My new title: animating assistant. Confusing? You bet. Two very similar titles could be two totally different jobs.

In supervising and directing for animation it can be confusing too. I would say that titles don’t matter but that would be a lie. Even if it’s not a big deal to you, it will be to studio executives, producers, unions and your attorney negotiating your deal. Contracts are fought over, offices are changed and salaries increased because of them. And yes, blame is pointed and respect is given based on your title. Titles change from studio to studio for the same job. One studio may call you an animation supervisor while another, the animation director. Both jobs could have the exact same responsibilities.

When I was negotiating my title credit with Sony Pictures for Stuart Little 2, I was told that the title promised me of “animation director” was not possible because of the DGA contract. The DGA is the Director’s Guild of America – the negotiating union working on behalf of live action directors. Basically, they had negotiated with all the studios a bylaw of their contract that said that there could only be one “director” title on a live action film and Stuart Little 2 was considered “a live action movie with post production visual effects.” That is, the animation of the title character that I oversaw and represented 70 percent of the film was considered a visual effect in the live action world. The film’s overall director was Robert Minkoff and since I was hired by Rob to oversee all aspects of the character animation I certainly didn’t want to take anything away from him so I settled on my credited title of Animation Supervisor. But, come to find out, Sony Pictures Imageworks already had their own Animation Supervisor title for someone working on the film so he had to become “Animation Supervisor – Sony Pictures Imageworks” in the final credits. It’s all so crazy. I was just happy to have worked on the film and would have taken Animation Dude if I thought it would make life simpler.

As the Animation Supervisor on Stuart Little 2, I also over saw the story team shown here.

Below I will define some of the more common titles in the world of animation and visual effects.

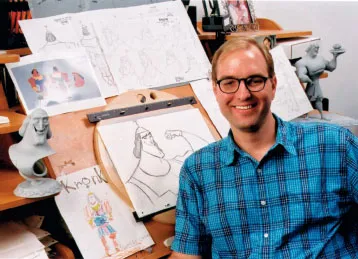

Supervising Animator

A senior or lead animator who has proven himself experienced enough in his or her work to shepherd a crew of animators under his or her supervision. This is the title I had at Disney Feature Animation on films such as The Lion King and The Emperor’s New Groove where I supervised the characters of Pumbaa and Kronk respectively. Of course the characters didn’t need any supervising but it meant that I had 3–4 other animators who worked under me on those characters. I was in charge of making sure those characters where consistent in look and performance throughout the entire film – not only in my work but my crew’s also.

Tony Bancroft Animation Supervisor of Kronk, Disney’s Emperor’s New Groove.

Animation Supervisor

This tends to be a senior animator that is in charge of all aspects of animation on a project, not just a character or a sequence. Oftentimes this is the title a person may have on a special effects project that is an animation/live action hybrid film. The Animation Supervisor would oversee the character animation crew working under the film’s overall live action director. This can be a difficult role as it can be an uncomfortable position being between the animators you supervise and the director who is your boss.

Animation Director

This term is used more in Japanese animation these days and refers to a senior animator who is in charge of entire sequences of the film. There would be multiple animation directors on one production with an overall director as their creative boss.

It has been used sparingly in the US because of the Director’s Guild of America agreement that I mentioned above.

From The Emperor’s New Groove. © 2000 Disney.

Director of an Animated Film

This is really the same as just plain old director. The rest of the title is how live action executives delineate for themselves who they are talking about when they speak of the director of an completely animated feature. Historically, most animated features have had more than one director. Mostly two directors (and in some cases four – whew!) that split the work load. For example, on Mulan I directed the film with my partner Barry Cook. In our case we split the directorial responsibilities by departments. Since Barry came from a background of effects animation and painting, it naturally fell to him to be in charge of layout, backgrounds and effects animation. While I came from a clean-up and character animation background so I was in charge of the clean-up and computer animation (used in the “Hun Charge” sequence mostly) departments. Then we shared the all important departments of story, character animation, editorial, ink and paint and all of postproduction. Making these responsibility splits helped the project become easier to control through the demanding and time-consuming phase of production.

Auteur Directing vs. Corporate “Brain Trust” Directing

Since a director is often times hired by a studio to direct an animated feature, it is important to understand the two totally different styles of directing that are coming out of the studios these days. There is the auteur style of directing and the corporate style of directing.

From Coraline. Courtesy of Laika, Inc. Henry Selick is an example of a director who uses auteur style direction.

Auteur style means the film reflects the director’s personal creative vision, as if they were the primary “auteur” (the French word for “author”). In spite of the production of the film being part of an industrial process, the author’s creative voice is distinct enough to shine through all kinds of studio interference and through the collective process. In recent years the best example of auteur-style animation directors are Hayao Miyazaki, Henry Selick, Nick Park, and even Chris Sanders. I say “even” Chris Sanders because unlike the other three mentioned he has developed his films in the highly corporate realm of a major studio which is unique for an auteur style of directing to exist. In the films directed by all of these individuals the viewer can clearly see the artist’s specific touch when it comes to the styling of the film, storytelling style, humor and quirky tone. The auteur-style director is afforded more control over his or her choices without interference for reasons unknown or as common as the producer’s faith in his or her direction. This style of directing is usually the luxury of an independent film company that is on the fringe of the major studios and therefore can take more chances with the content of their film canon.

The opposite is the corporate style of directing which has been popularized more recently by many studios’ mandate that none of their films will be developed outside of their own corporate “brain trust” group. The brain trust is made up of the company’s top directors and story people that give constant input into all features and shorts produced at the studio. This corporate style is often called directing by committee for the obvious reason that all substantial story decisions are reached through consensus of a group. Many major animation studios work under the committee system. They are the commercial films that don’t particularly feel personal but do connect with the widest possible audience. Why? Because they are pure entertainment! And that is why most movie watchers go to theatres – to be entertained. But with so many ou...