eBook - ePub

The New Economic Criticism

Studies at the interface of literature and economics

This is a test

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The New Economic Criticism

Studies at the interface of literature and economics

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection brings together twenty-seven essays by influential literary and cultural historians, as well as representatives of the vanguard of postmodernist economics. Contributors include: Jean-Joseph Goux, Marc Shell. This is a pathbreaking work which develops a new form of economic analysis. It will appeal to economists and literary theorists with an interest beyond the narrower confines of their subject.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The New Economic Criticism by Martha Woodmansee,Mark Osteen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

LANGUAGE AND MONEY

2

THE ISSUE OF REPRESENTATION

Marc Shell

A descriptive analysis of bank notes is needed. The unlimited satirical force of such a book would be equaled only by its objectivity. For nowhere more naively than in these documents does capitalism display itself in solemn earnest.

(Benjamin 1979b:96)

The United States, the first place in the Western world where paper money was widely used,1 is an interesting locale for the study of representation and exchange in art. This is not only because the United States sometimes presents itself as a “secular”—hence supposedly non-Christian—state. It is also because in nineteenth-century America there raged an extensive debate about paper money that, like the discussion of coinage in “religious” Byzantium, had aesthetic as well as political implications.

In the American debate, which blended the self-interested struggle between “hard money” creditors and “soft money” debtors with various disputes about the issue of representation, “paper money men” (as advocates of paper money were called) were set against “gold bugs” (advocates of gold).2 It was shadowy art against golden substance. The zealous backers of solid specie associated gold with the substance of value and disparaged all paper as the “insubstantial” sign. A piece of paper counted for relatively little as a commodity and thus, they said, was “insensitive” in the system of economic exchange. Over the first half of the century, paper issued by banks (and supposedly backed by gold) was their primary focus. During the Civil War, controversy swirled over the government-issued “greenbacks”—monetary paper backed by no metal at all. Monometallists, at the end of the century, grew alarmed when some politicians wanted the government to declare silver to be money and to issue banks notes on this augmented monetary “base.”

Credit, or belief, involves the ground of aesthetic experience, and the same medium that confers belief in fiduciary money (bank notes) and in scriptural money (accounting records and money of account, created by the process of bookkeeping) also seems to confer it in art. So the “interplay of money and mere [drawing or writing] to a point where,” as Braudel says, “the two be[come] confused” involved the tendency of paper money to play upon the everyday understanding of the relation between symbols and things.3 The sign of the monetary diabolus, which Americans said was like the sign impressed in Cain’s forehead,4 became the principal icon of America.

The American debates, viewed historically, were a plank in a cultural bridge to the contemporary world of electronic credits and transfers and government money unbacked by metal or other material substance. The shift from substance to inscription in the monetary sphere began early, with the first appearance of coins. Coins as such were fiduciary ingots that passed for the values inscribed—values to which the metallic purity and weight of the coins themselves might be inadequate—thanks to a general forbearance and acceptance of the issuing authority on the part of buyers and sellers. Whether or not this workaday tolerance of political authority came on the heels of traders customarily overlooking the clips and wear and tear in old-fashioned ingots, the first appearance of coins precipitated a quandary over the relation between face value and substantial value—between, as it were, intellectual currency and material currency. As early as Heraclitus and Plato, idealist thinkers had wondered about the link of monetary hypothesizing with logical hypothesizing, or monetary change making with dialectical division. But awareness of the specific difference between inscription and thing exploded with the introduction of paper money.

For Americans the value of paper—the material substance on which monetary engravings were now printed—clearly had next to nothing to do with paper notes’ value as money. Bank notes were backed by land; or by gold in a vault somewhere; or by silver; or by loans; or perhaps by actual or potential government power. (Exitus in dubio est, “the issue is in doubt,” read the “continental” notes of the American Revolution.) But the precise connection between gold and paper seemed the stuff of mystery. Paper money thus regenerated a cultural disturbance that extended beyond money per se to include the artistic experience.

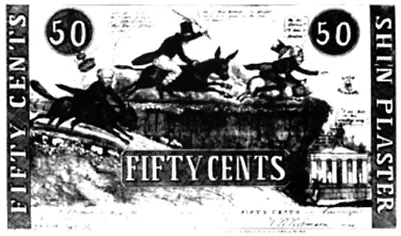

In Poe’s famous story “The Gold-Bug,” the treasure-hunting protagonist cashes in a devilishly “ideal” cryptographic drawing for “real” gold. The link between the economic and aesthetic realms that drives Poe’s protagonist, with his golden bug and his bug for gold, is expressed inadvertently in Gold Humbug, H.R.Robinson’s “joke” note depicting a devilish treasure hunt for the gold that “real” notes (“gold humbug”) are supposed to represent (Plate 2.1). He and Napolean Sarony represented themselves as sellers of artful joke notes in much the same way that they represented bankers and legislators as sellers of genuine or counterfeit notes.5 (Likewise, Johnson, in his joke note Great Locofoco Juggernaut, made the usual association of gold deposits, which back up paper money, with fecal deposits, which issue from the backside.)6

These American cartoonists worked within a tradition that includes France in the 1790s and Germany in the 1920s. “Bombario” of eighteenth-century Europe, who is named on the idealist Don Quixote’s saddles in cartoons from the John Law paper money fiasco (Plate 2.2), became the gold humbug of nineteenth-century America.

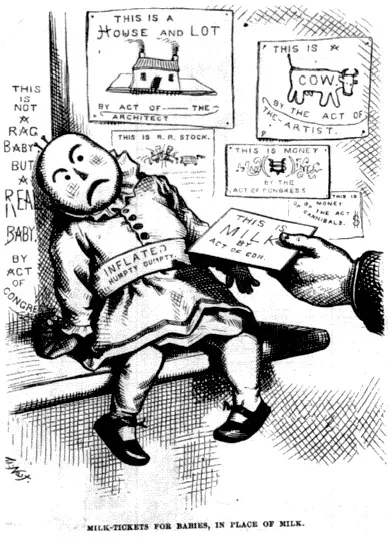

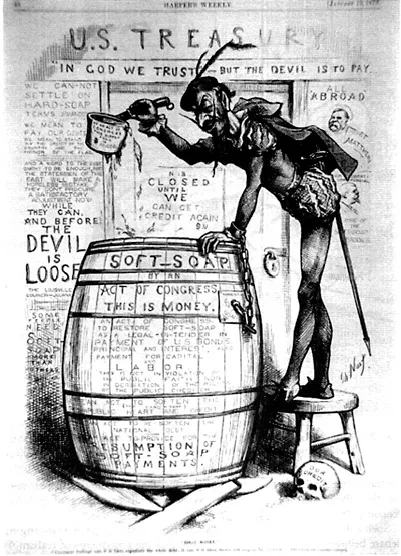

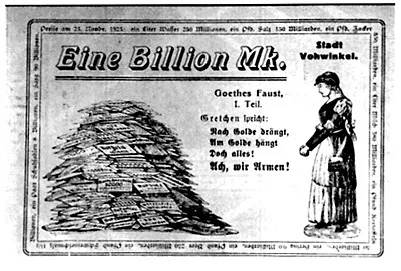

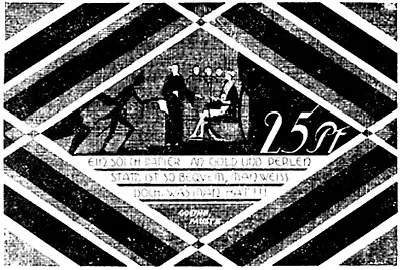

Thomas Nast’s cartoon A Shadow is Not a Substance (Plate 2.3), which appears in Wells’s Robinson Crusoe’s Money (1876), depicts the relation between reality and idealist appearance as both monetary and aesthetic; and it helps to explain many American artists’ and economists’ association of paper money with spiritualness, or ghostliness,7 and their understanding of how an artistic appearance is taken for the real thing by a devilish suspension of disbelief. Congress, it was said, could turn paper into gold by an “act of Congress,” like the devilish Tat (deed) at issue in the paper money scene orchestrated by Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust. Why could not a Faustian artist turn paper with a design or story on it into gold? Thus Nast’s cartoon Milk Tickets for Babies, in Place of Milk (Plate 2.4), also from Wells’s book, shows one paper bearing the design of a milk cow and the inscription “This is a cow by the act of the artist,” and another paper that reads “This is money by the act of Congress”; his Ideal Money has similar inscriptions reading “Soft-Soap/by an /Act of Congress/This is Money” and “By an Act of Congress this Dipper Full is $10,000” (Plate 2.5). (Some Notgeld, or “emergency money,” from Germany of the inflationary 1920s quotes Faust and includes the inscription: “One liter of milk for 550 billion German marks” (Plate 2.6). Other German emergency bank notes ironically quote passages from Faust like “Such currency…bears its value on its face” (Plate 2.7).)

Plate 2.1 H.R. Robinson, Gold Humbug, caricature of a shinplaster, United States, 1837. At the right, Andrew Jackson chases the “gold humbug.” Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Plate 2.2 opposite: Cartoon, John Law as Don Quixote, Netherlands, 1720. “Law, als een tweede Don-Quichot, op Sanches Graauwtje zit ten Spot” [Law, like another Don Quixote, sits on Sancho’s ass, being everyone’s fool]. The engraving shows John Law riding an ass. On the flag is “lk koom. Ik koom Dulcinea” [I come, I come Dulcinea]. A coffer filled with bags of money is inscribed “Bombarioos Geld kist 1720” [Bombario’s (humbug’s) money box, 1720]. Behind Law is a devil, the “Henry” of the text; he holds up the tail of the ass. The ass voids papers inscribed 1000,0,00, and so on. From Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid (Amsterdam, 1720) Buffalo and Erie County Library, Buffalo, New York.

The American debate about paper money was concerned with symbolization in general, hence with both money and aesthetics. Symbolization in this context concerns the relation between the substantial thing and its sign. Solid gold was conventionally associated with the substance of value. Whether or not one regarded paper as an inappropriate and downright misleading “sign,” that sign was “insubstantial” insofar as the paper counted for nothing as a commodity and was thus “insensible” in the economic system of exchange. (The French symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who was much interested in the international Panama financial scandal—during the decade of the 1890s when Americans were focusing on the Cross of Gold presidential campaigns—wrote in this context that “everything is taken up in Aesthetics and in Political Economy.”8)

Plate 2.3 Thomas Nast, A Shadow Is Not a Substance, 1876. From Wells,Robinson Crusoe’s Money. Harvard College Library.

The American debate about aesthetics and economics connected the study of the essence of money with the philosophy and iconology of art. Joseph G.Baldwin thus explored how paper money asserts the spiritual over the material;9 and Albert Brisbane, in his midcentury Philosophy of Money, provided an “ontology,” as he called it, for the study of monetary signs. Clinton Roosevelt, a prominent member of the Locofocos (a political party of the period), argued in his Paradox of Political Economy in 1859, when the “gold bug” Van Buren had lost the presidency, that the American Association for the Advancement of Science should establish an “ontological department for the discussion and establishment of general principles of political economy.”10

Such a discussion already existed in Germany in the shape of a far-ranging debate between the proponents of idealism and the proponents of realism. It was this debate that Thomas Nast brought to American newspaper and book readers in the second half of the century in such Germanic cartoons as his devilish Ideal Money (Plate 2.5). For Nast and his collaborator Wells—as for many Americans living during the heyday of paper money controversies and trompe l’oeil art—paper could no more be money than “a shadow could be the substance, or the picture of a horse a horse.”11

The problem, from the viewpoint of aesthetics, involves representation as exchange. A painting of grapes, a painting of a pipe, or a monetary inscription generally stands for something else—it makes the implicit claim: “I am edible grapes,” “I am a pipe,” or “I am ten coins.” Sometimes observers are trumped into taking the imitation for the real. For example, birds are said to have pecked themselves to death on the grapes painted by the ancient Greek artist Zeuxis. (He was the first artist known to become very rich.)12 People who read the inscription under Magritte’s trompe l’oeil (trumping, or fooling the eye) pipe may never roll up the canvas and smoke it like a cigar (Plate 2.8),13 but Magritte here plays with our “commonsense” suspension of disbelief when we approach an artistic representation. We take the painting for a pipe on some level. But pipes and grapes, however much they are representable artworks, are also more or less “original” objects.14 Money, on the other hand, is not. A piece of paper money is almost always a representation, a symbol that claims to stand for something else or to be something else. It is not that paper depicts and represents coins, but that paper, coins, and money, generally, all stand in the place of something else.

Plate 2.4 Thomas Nast, Milk-Tickets for Babies, in Place of Milk, 1876. From Wells, Robinson Crusoe’s Money. Harvard College Library.

Ptate 2.5 Thomas Nast, Ideal Money, From Harper’s Weekly 48 (19 January 1878). Beneath the title, Ideal Money, in small script: “‘Universal Suffrage can, if it likes, repudiate the whole debt; it can, if it likes, decree soft-soap to be currency.’—The Louisville Courier-Journal”. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Plate 2.6 Emergency money (Notgeld), bank note, Eine Billion Mk. (American, one trillion German marks; British, one billion German marks), Stadt Vohwinkel, November 1923. Quoting Goethe’s Faust, 2802–4: “For gold contend,/On gold depend/All things and men… Poor us!” In right border, beginning at top: “550 Milliarden, ein Liter Milch” (American, one liter of milk for 550 billion German marks) Money Museum of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt.

Plate 2.7 Emergency money (Notgeld), bank note, Schleswig-Holstein, 1920s. Quoting the paper money scene from Goethe’s Faust, 6119–20: “Such currency, in gold and jewels’ place,/Is neat, it bears its value on its face” (trans. Arndt). Money Museum of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt.

(Just as bank notes sometimes visually suggest that they represent or are coins, as do the American bank notes in Plate 2.9 [Hessler 1974:17] and various Chinese bills that depict rolls of coins,15 so postage stamps often depict monetary tokens, as do those in Plate 2.10, and issuing postal authorities frequently claim the banker’s prerogative to issue regular currency.16 Similarly, some playing cards suggest visually that they represent or are coins, much as the coins they represent suggest specie: examples would include the round coinlike cards from the “suit of coins” in Plate 2.11 and the tarot knight holding a coin in Plate 2.12.17 Playing cards as such are linked with the historical beginnings of paper money, and even in the modern era playing-card money has been issued during periods of financial crisis.18 In gambling card games, moreover, the relation between what is played with and what is played for—the playing card as numeric marker and as money—is like that in such coin games as “heads or tails” (croix et piles). Blaise Pascal used this game to help explain why it is best to bet on the existence of God and the true croix, or cross; and probability theorists and econometricians generally have used this game to exp...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- PLATES

- NOTES ON THE CONTRIBUTORS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: LANGUAGE AND MONEY

- PART II: CRITICAL ECONOMICS

- PART III: ECONOMICS OF THE IRRATIONAL

- PART IV: ECONOMIC ETHICS: DEBTS AND BONDAGE

- PART V: ECONOMIES OF AUTHORSHIP

- PART VI: MODERNISM AND MARKETS

- PART VII: CRITICAL EXCHANGES