This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Sea Voyage Narrative

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From The Odyssey to Moby Dick to The Old Man and the Sea, the long tradition of sea voyage narratives is comprehensively explained here supported by discussions of key texts.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Sea Voyage Narrative by Robert Foulke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Literaturkritik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Nature of Voyaging

It is best to begin with human attitudes toward the sea because they spawn the prolific outpouring of sea writing and generate the most striking features of sea voyage narratives. Such attitudes may at first appear to be nothing but the romantic wanderlust of John Masefield’s most famous lyric, “Sea Fever”:

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face and a grey dawn breaking.

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face and a grey dawn breaking.

In spite of such exuberant stanzas, Masefield also recognized the ironic dichotomies of life at sea, noting that beautiful sailing ships were filled with battered and degraded human beings:

A barquentine was being towed out by a dirty little tug; and very far away, shining in the sun, an island rose from the sea, whitish, like a swimmer’s shoulder. It was a beautiful sight that anchorage with the ships lying there so lovely, all their troubles at an end. But I knew that aboard each ship there were young men going to the devil, and mature men wasted, and old men wrecked; and I wondered at the misery and sin which went to make each ship so perfect an image of beauty.1

For seamen, even novices like Masefield, attitudes toward the sea and seafaring are usually quite complex and contradictory, built around polarities of awe and fear, ennui and anxiety, exaltation and despair, and they often embody—simultaneously—the literary forms of romance and irony.

The sea both attracts and repels, calling us to high adventure and threatening to destroy us through its indifferent power. In The Mirror of the Sea Conrad untangles the intertwined bundle of human attitudes generated by the sea:

For all that has been said of the love that certain natures (on shore) have professed to feel for it, for all the celebrations it had been the object of in prose and song, the sea has never been friendly to man. At most it has been the accomplice of human restlessness, and playing the part of dangerous abettor of world-wide ambitions. Faithful to no race after the manner of the kindly earth, receiving no impress from valour and toil and self-sacrifice, recognizing no finality of dominion, the sea has never adopted the cause of its masters like those lands where the victorious nations of mankind have taken root, rocking their cradles and setting up their gravestones. He—man or people—who, putting his trust in the friendship of the sea, neglects the strength and cunning of his right hand, is a fool! As if it were too great, too mighty for common virtues, the ocean has no compassion, no faith, no law, no memory. Its fickleness is to be held true to men’s purposes only by an undaunted resolution and by a sleepless, armed, jealous vigilance, in which, perhaps, there has always been more hate than love. Odi et amo may well be the confession of those who consciously or blindly have surrendered their existence to the fascination of the sea…. Indeed, I suspect that, leaving aside the protestations and tributes of writers who, one is safe in saying, care for little else in the world than the rhythm of their lines and the cadence of their phrase, the love of the sea, to which some men and nations confess so readily, is a complex sentiment wherein pride enters for much, necessity for not a little, and the love of ships—the untiring servants of our hopes and our self-esteem—for the best and most genuine part.2

In this passage Conrad the writer surely heeds the rhythm of his lines and the cadence of his phrases, but he had been a seaman for nearly a quarter of a century and had serious business at

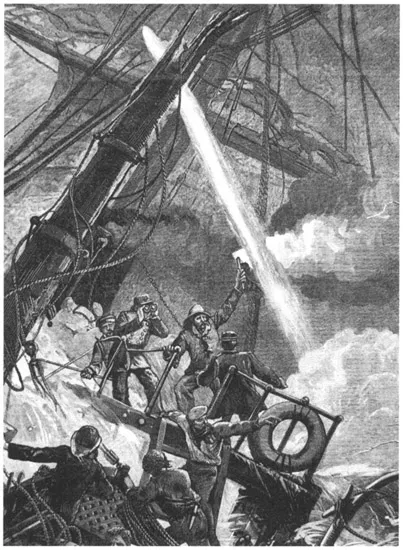

”Disabled in mid-ocean—firing signals of distress.” Drawn by J. O. Davidson for Harper’s Weekly, 10 December 1881.

Courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum.

Courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum.

hand. In The Mirror of the Sea, the narrative that follows this passage—not fiction—tells of coming upon a dismasted sailing ship on a pleasant day at sea and snatching the exhausted and beaten crew off the deck just before the ship sinks. Conrad’s anthropomorphic theme in introducing this narrative, the “unfathomable cruelty” of the sea, is by no means dated, as anyone who has followed seafaring disasters in the last few years knows—an English Channel ferry, a Baltic ferry, a Greek cruise ship off South Africa, with graphic television footage of its final plunge, and countless sinkings of supertankers, container ships, and yachts that do not make the news. In John McPhee’s Looking for a Ship, Captain Washburn tells a truth of contemporary seafaring succinctly: “Every day, somewhere someone is getting it from the weather. They’re running aground. They’re hitting each other. They’re disappearing without a trace.”3 (Indeed they are. During the writing of this chapter, the 450-foot Ukrainian cargo ship Salvador Allende, en route from Texas to Helsinki with a cargo of rice, sank in a North Atlantic gale with 65-knot winds and 35-foot seas; in this case there was a trace: two survivors out of 31 persons on board.) In the era before radio communications at sea, sinkings were more often than not mysterious disappearances. In another section of The Mirror of the Sea, Conrad captures the ominous uncertainty surrounding ships that simply vanish; at first they are reported overdue and then posted missing:

How did she do it? In the word “missing” there is a horrible depth of doubt and speculation. Did she go quickly from under the men’s feet, or did she resist to the end, letting the sea batter her to pieces, start her butts, wrench her frame, load her with increasing weight of salt water, and dismasted, unmanageable, rolling heavily, her boats gone, her decks swept, had she wearied her men half to death with unceasing labor at the pumps before she sank with them like a stone? (Mirror, 59)

The booming industry of making films about the Titanic reminds us of the metaphoric power of sinkings, some of which are taken to be emblematic of whole eras in history or the fragility of human enterprise.

One of the oldest emblems in sea literature is Odysseus’s oar, symbolizing the unnaturalness of treading the “sea-road,” as the Homeric formula is often translated, and introducing the motif of leaving the sea forever. To complete his penance for offending Poseidon, Odysseus is told to

go forth once more, you must…

carry your well-planed oar until you come

to a race of people who know nothing of the sea,

whose food is never seasoned with salt, strangers all

to ships with their crimson prows and long slim oars,

wings that make ships fly. And here is your sign—

unmistakeable, clear, so clear you cannot miss it:

When another traveler falls in with you and calls

that weight across your shoulder a fan to winnow grain,

then plant your bladed, balanced oar in the earth

and sacrifice fine beasts to the lord god of the sea,

Poseidon—4

carry your well-planed oar until you come

to a race of people who know nothing of the sea,

whose food is never seasoned with salt, strangers all

to ships with their crimson prows and long slim oars,

wings that make ships fly. And here is your sign—

unmistakeable, clear, so clear you cannot miss it:

When another traveler falls in with you and calls

that weight across your shoulder a fan to winnow grain,

then plant your bladed, balanced oar in the earth

and sacrifice fine beasts to the lord god of the sea,

Poseidon—4

The theme of escaping bondage to the sea and living out of sight of it persists throughout sea literature from Homer to Conrad and is often associated with Odysseus’s emblematic oar. That oar surfaces again in the refrain of “Marching Inland,” a sea ballad from the Canadian Maritimes:

I’m marching inland from the shore,

Over me shoulder I’m carrying an oar,

When someone asks me “What is that funny thing you’ve got,”

Then I know I’ll never go to sea no more, no more,

Then I know I’ll never go to sea no more.5

Over me shoulder I’m carrying an oar,

When someone asks me “What is that funny thing you’ve got,”

Then I know I’ll never go to sea no more, no more,

Then I know I’ll never go to sea no more.5

Among the reasons for going ashore and staying there, the ballad suggests it as Lord Nelson’s cure for seasickness, reminds us that Columbus ran aground on the New World while trying to reach the Far East, remembers the fate of Drake and Grenville, famous sailors who never came home, and concludes with the admonition never to cast one’s anchor less than 90 miles from shore.

Settling any closer might tempt one to return to the sea-road. This is precisely what Tennyson does to an older Ulysses, reversing the polarity of desire during the long and difficult voyage home. His restive Ulysses, stuck with an aging Penelope and an unimaginative Telemachus, cannot wait to quit the Ithaca he sought for a full decade:

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail;

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toiled, and wrought, and thought with me,—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honor and his toil.

Death closes all; but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks;

The long day wanes; the slow moon climbs; the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

’Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.6

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toiled, and wrought, and thought with me,—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honor and his toil.

Death closes all; but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks;

The long day wanes; the slow moon climbs; the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

’Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.6

This Victorian Ulysses strikes out on a new voyage of discovery, while one of his twentieth-century successors, the hero of Nikos Kazantzakis’s Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, also leaves Ithaca to create new havoc in the aftermath of the Trojan War and embark on a symbolic dark journey through ancient Egypt and primordial Africa toward death. These reworked heroes, one romantic and the other thoroughly ironic, reflect both the tenor of their ages and the radically different possibilities inherent in voyaging. Tennyson and Kazantzakis did not misread the Odyssey but simply pulled out of it the burning curiosity that launches Odysseus’s adventures and usually gets him in desperate trouble.

The polarity between the urge to explore unknown seas and the longing to return home emerges most directly and poignantly in an anonymous Anglo-Saxon lyric, “The Seafarer”:

Little the landlubber, safe on shore,

Knows what I’ve suffered in icy seas

Wretched and worn by the winter storms,

Hung with icicles, stung by hail,

Lonely and friendless and far from home.

In my ears no sound but the roar of the sea,

The icy combers, the cry of the swan;

In place of the mead-hall and laughter of men

My only singing the sea-mew’s call,

The scream of the gannet, the shriek of the gull;

Through the wail of the wild gale beating the bluffs

The piercing cry of the ice-coated petrel,

The storm-drenched eagle’s echoing scream.

In all my wretchedness, weary and lone,

I had no comfort of comrade or kin

Yet still, even now, my spirit within me

Drives me seaward to sail the deep,

To ride the long swell of the salt sea-wave.

Never a day but my heart’s desire

Would launch me forth on the long sea-path,

Fain of fair harbors and foreign shores.

Yet lives no man so lordly of mood,

So eager in giving, so ardent in youth,

So bold in his deeds, or so dear to his lord,

Who is free from dread in his far sea-travel,

Or fear of God’s purpose and plan for his fate.

Knows what I’ve suffered in icy seas

Wretched and worn by the winter storms,

Hung with icicles, stung by hail,

Lonely and friendless and far from home.

In my ears no sound but the roar of the sea,

The icy combers, the cry of the swan;

In place of the mead-hall and laughter of men

My only singing the sea-mew’s call,

The scream of the gannet, the shriek of the gull;

Through the wail of the wild gale beating the bluffs

The piercing cry of the ice-coated petrel,

The storm-drenched eagle’s echoing scream.

In all my wretchedness, weary and lone,

I had no comfort of comrade or kin

Yet still, even now, my spirit within me

Drives me seaward to sail the deep,

To ride the long swell of the salt sea-wave.

Never a day but my heart’s desire

Would launch me forth on the long sea-path,

Fain of fair harbors and foreign shores.

Yet lives no man so lordly of mood,

So eager in giving, so ardent in youth,

So bold in his deeds, or so dear to his lord,

Who is free from dread in his far sea-travel,

Or fear of God’s purpose and plan for his fate.

(Moods, 27-28)

Here we have it all in simple contiguity—cold, misery, and loneliness in an environment devoid of human comfort set against renewed wanderlust and the urge to sail, tempered by justifiable fear. A few lines later the word haunted appears, and that is perhaps the most appropriate summary of the combined lure and dread, love and hate, that characterizes seafarers’ attitudes toward the unstable ocean that mirrors an equally mutable sky. Living at this interface always holds out the possibility of extraordinary experience. Thus it is not surprising to find Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner haunted by his extraordinary tale, one that he must tell to an unwilling but mesmerized wedding guest ashore, or to understand the overpowering obsession that corrupts Captain Ahab’s imagination.

All of these continuities of attitude, and many more, suggest that unique qualities in sea experience may, in part, account for the shape and persistent themes of voyage narratives. Such possibilities are best approached through questions. For example, in narratives so closely related to fact, to the tedium of daily routine on board ships at sea, and in a profession that constantly demands hardheaded realism and attention to detail, why are nostalgia, romance, and meditation so prevalent? To what extent does the linearity and episodic nature of voyaging determine patterns of narration? Are there any fundamental psychological elements present in all voyage experience, and if so, what are they? Some answers emerge from my own sea experience over forty years, buttressed by wide reading in the genre.

The environment of long sea passages promotes reflection in thoughtful seafarers. Once committed to the open sea, human beings are enclosed irrevocably by the minute world of the vessel in a vast surround. That world reverses many physical and social realities. Ashore, healthy human beings desire bodily movement and gain a sense of freedom and power through it; at sea, motion is imposed upon them, with temporary but debilitating effects. Again, many individuals ashore can join and leave groups at will, but at sea all are compressed within a single, unchanging society, and one traditionally marked by a rigid hierarchy at that. It is often possible to choose a solitary life ashore, or at least regulate contact with others, but at sea the absolute isolation of the ship makes adapting to the fixed society on board unavoidable. In this fragmentary but self-contained world, seafarers have time on

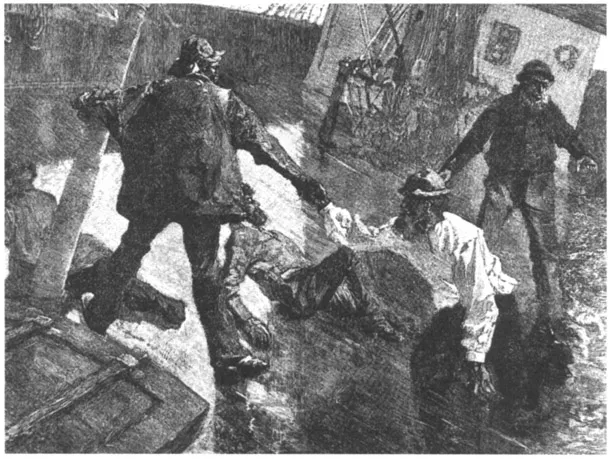

“In a heavy sea.” Century Magazine, June 1882.

Courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum.

Courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum.

their hands, and they spend much of it standing watch—literally watching the interaction of ship, wind, and sea while waiting for something, or nothing, to happen. Their world demands keen senses because they live on an unstable element that keeps their home in constant motion, sometimes soothing them with a false sense of security, sometimes threatening to destroy them.

Although the vision of those at sea is bounded by a horizon and contains a seascape of monotonous regularity, what is seen can change rapidly and unpredictably. Unlike the land, the sea never retains the impress of human civilization, so seafarers find their sense of space suggesting infinity and solitude on the one hand and prisonlike confinement on the other. That environment contains in its restless motion lurking possibilities of total disorientation: In a knockdown walls become floors, doors become hatches. In Conrad’s magnificent novella Typhoon, an obtuse but orderly Captain MacWhirr first realizes that he may lose his ship not by watching the furious seas that engulf her but by going below and finding his cabin in total disarray.

The seafarer’s sense of time is equally complex. It is both linear and cyclical: Time is linear in the sense that voyages have beginnings and endings, departures and landfalls, starting and stopping points in the unfolding of chronological time; yet time is also cyclical, just as the rhythm of waves is cyclical, because the pattern of a ship’s daily routine, watch on and watch off, highlights endless recurrence. Space and time have always merged more obviously at sea than they do in much of human experience. The simple act of laying out a ship’s track on a chart by using positions determined on successive days connects time and space visibly. The nautical mile, spatially equivalent to one minute of latitude, is also the basis of the knot, a measure of speed in elapsed time. Until late in the eighteenth century European navigators calculated their position by deduced reckoning, measuring the number of miles they had sailed a particular course by combining time and speed. The invention of reliable chronometers made more precise celestial navigation possible by interlocking measurements of time and space in a more sophisticated way. Before the era of electronic global positioning systems, to find longitude one had to have a precise reading of the time at Greenwich, England. Then to get an accurate fix of the ship’s position, one added a spatial measurement by taking the altitude of the sun at noon or of a star at dawn or dusk. What wonder that mariners tended to be reflective when they had to deal with abstract time and celestial space just to find out where they were in the watery world? Control of such world-encompassing dimensions can lead to delusions, too, when it lures seafarers into manipulating navigational reality. Like one of the competitors in a single-handed race around the world in the 1960s, Owen Browne, protagonist of Robert Stone’s Outerbridge Reach, fabricates false positions; when Browne can no longer “pursue the fiction of lines” and is weary “of pretending to locate himself in space and time,” he jumps overboard.7

Voyages also suggest larger patterns of orientation because they have built-in directionality and purpose, an innate teleology. We embark on voyages not only to get somewhere but also to accomplish something and, in Western culture, often to discover more about the ways human beings can expect to fare in the world. The epic voyages of Odysseus, Jason, and Aeneas were freighted with metaphor as well as adventure, and that characteri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- General Editor’s Statement

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Chapter 1 The Nature of Voyaging

- Chapter 2 Navigation and the Oral Tradition: The Odyssey

- Chapter 3 Voyages of Discovery: Columbus and Cook

- Chapter 4 The Sea Quest: Moby-Dick and The Old Man and the Sea

- Chapter 5 Voyages of Endurance: The Nigger of the “Narcissus”

- Chapter 6 Postscript: Voyage Narratives in the Twentieth Century

- Notes and References

- Bibliographic Essay

- Recommended Reading

- Index