eBook - ePub

Performance Analysis

An Introductory Coursebook

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Performance Analysis

An Introductory Coursebook

About this book

This revolutionary introductory performance studies coursebook brings together classic texts in critical theory and shows how these texts can be used in the analysis of performance.

The editors put their texts to work in examining such key topics as:

* decoding the sign

* the politics of performance

* the politics of gender and sexual identity

* performing ethnicity

* the performing body

* the space of performance

* audience and spectatorship

* the borders of performance.

Each reading is clearly introduced, making often complex critical texts accessible at an introductory level and immediately applicavble to the field of performance. The ideas explored within these readings are further clarified through innovative, carefully tested exercises and activities.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part one

Decoding the artefact

If there is any common ground to the theories which dominated twentieth-century thought, it is their collective recognition of the distance separating the material world from our perceptions of it. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) highlighted the role of the unconscious and of psychic experiences in shaping actions and perceptions, while Marxism stressed the capacity of ideology to determine our view of the real. For Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913) the individual never encountered the real world, only a version of it already mediated by sign systems, whereas Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) saw reality as an unknowable void, all attempts to know it being merely projections. Albert Einstein (1879–1955) demonstrated that views of macro-physical phenomena are determined by our position relative to them, just as Werner Heisenberg (1901–76) showed how, on the scale of micro-physics, the act of perceiving inevitably alters the perceived. Phenomenology and various strands of existentialism focused on consciousness’s construction of reality, while the theorists on whose work modern sociological thought was to be founded – Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), Max Weber (1864–1920) and Karl Marx (1818–83) – all stressed the social origins of conceptions of the real. Albeit that they are very different, all these theories and theorists acknowledge that our perceptions of the world and its objects, the meanings we ascribe to them, are made, produced in the gaze of the perceiver. This general recognition developed in the second half of the century into a focus on the cultural processes involved in the manufacture of meaning, with structuralism and post-structuralism, semiotics, writings in psychoanalysis and feminism, and theories of ideology and postmodernism, exploring how ‘reality’ is constructed. Across the range of these later perspectives two key assumptions are shared. The first is that meaning does not exist in some abstract realm of thought but always involves the concrete. It is not simply that physical images, actions or words are necessary to communicate meaning; rather, meaning itself is born in the marriage of material object or action and immaterial concept – in the sign. The second is that meaning is always social in origin. The word ‘cat’ has no innate quality of cat-ness, its significance is conventional, the product of an implicit agreement between members of a given interpretative community.

The excerpts in this section introduce concepts which are fundamental to the reading of cultural artefacts in general, and which may be used alongside most of the writings reproduced in the rest of the volume. The pieces are organized developmentally, each establishing foundations that are built upon in the next. Saussure and Charles S. Peirce (1839–1914) outline their own, very different theories of the sign. Roland Barthes (1915–80) elaborates on the vantage offered by Saussure, showing how individual signs draw upon or are implicated in wider sign systems, the text reaching beyond its own confines in its generation of meaning. Claude Lévi-Strauss (b. 1908) broadens the perspective further, situating elements of narrative within the systematic organization of culture as a whole. Erving Goffman (1922–88) examines the mechanism by which the acts and objects of this culture are isolated as meaningful.

Further reading: Belsey 1980, Culler 1981 and Eagleton 1983 provide good, accessible introductions to the kinds of theoretical positions examined in this part of the reader; Carlson 1990, Fortier 1997 and Whitmore 1994 survey theories particularly useful in the analysis of performance, while Counsell 1996, Pavis 1982 and Reinelt and Roach (eds) 1992 offer working analyses of actual productions or practices; Barthes 1977, Berger 1972, Bignell 1997 and Williamson 1978 are comparable approaches to other disciplines and, as well as being interesting in themselves, provide ideas and insights relevant to performance analysis.

1.1 The sign

Ferdinand de Saussure, from Course in General Linguistics, trans. Wade Baskin, London: Fontana, 1974 [originally published 1916], and Charles S. Peirce, first published in Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, eds Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1964

[Semiotics or semiology, the terms used by Peirce and Saussure respectively, involves addressing physical objects in terms of their ability to convey meaning: as signs. For Saussure, the sign is more than a means of communication, it comprises the basic fabric of culture. Saussurean signs do not merely express existing meanings, they are the mechanisms by which meaning is created, for in fixing abstract concepts (signifieds) to material objects (signifiers), sign systems provide the structures in which thought occurs, shaping our perceptions and experiences. Born out of the US philosophical tradition of pragmatism, with its focus on the practical function of ideas, Peirce’s theory is less concerned with the constructive power of signs than with how they work. In distinguishing between the various forms, his three-part scheme of icon, index and symbol reflects the different kinds of connection that can exist between signs and their referents, the means by which one is able to signify the other. The influence of Saussurean semiology is vast, underpinning the broad movement of structuralism and, as an antagonist, post-structuralism (see Barthes, Lévi-Strauss, Foucault), and evident in work in a range of areas from psychoanalysis and feminism to theories of ideology. Peircean semiotics is less pervasive, and is most often encountered today in writing on performance.]

Ferdinand de Saussure, from Course in General Linguistics

Sign, signifier, signified

Some people regard language, when reduced to its elements, as a namingprocess only – a list of words, each corresponding to the thing that it names.

This conception is open to criticism at several points. It assumes that ready-made ideas exist before words; it does not tell us whether a name is vocal or psychological in nature (arbor, for instance, can be considered from either viewpoint); finally, it lets us assume that the linking of a name and a thing is a very simple operation – an assumption that is anything but true. But this rather naive approach can bring us near the truth by showing us that the linguistic unit is a double entity, one formed by the association of two terms.

We have seen in considering the speech-circuit that both terms involved in the linguistic sign are psychological and are united in the brain by an associative bond. This point must be emphasized.

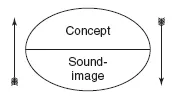

The linguistic sign unites, not a thing and a name, but a concept and a sound-image. The latter is not the material sound, a purely physical thing, but the psychological imprint of the sound, the impression that it makes on our senses. The sound-image is sensory, and if I happen to call it ‘material’, it is only in that sense, and by way of opposing it to the other term of the association, the concept, which is generally more abstract. [. . .]

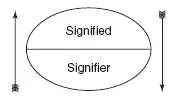

The linguistic sign is then a two-sided psychological entity that can be represented in Figure 1. The two elements are intimately united, and each recalls the other. Whether we try to find the meaning of the Latin word arbor or the word that Latin uses to designate the concept ‘tree’, it is clear that only the associations sanctioned by that language appear to us to conform to reality, and we disregard whatever others might be imagined.

Figure 1

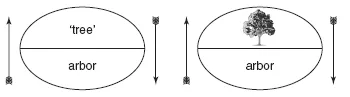

Our definition of the linguistic sign poses an important question of terminology. I call the combination of a concept and a sound-image a sign, but in current usage the term generally designates only a sound-image, a word, for example (arbor, etc.). One tends to forget that arbor is called a sign only because it carries the concept ‘tree’, with the result that the idea of the sensory part implies the idea of the whole (Figure 2). Ambiguity would disappear if the three notions involved here were designated by three names, each suggesting and opposing the others. I propose to retain the word sign (signe) to designate the whole and to replace concept and sound-image respectively by signified (signifié) and signifier (signifiant); the last two terms have the advantage of indicating the opposition that separates them from each other and from the whole of which they are parts. [. . .]

Figure 2

The arbitrary nature of the sign

The bond between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary. Since I mean by sign the whole that results from the associating of the signifier with the signified, I can simply say: the linguistic sign is arbitrary.

The idea of ‘sister’ is not linked by any inner relationship to the succession of sounds s-ö-r which serves as its signifier in French; that it could be represented equally by just any other sequence is proved by differences among languages and by the very existence of different languages: the signified ‘ox’ has as its signifier b-ö-f on one side of the border and o-k-s (Ochs) on the other. [. . .]

The word arbitrary also calls for comment. The term should not imply that the choice of the signifier is left entirely to the speaker (we shall see below that the individual does not have the power to change a sign in any way once it has become established in the linguistic community); I mean that it is unmotivated, i.e. arbitrary in that it actually has no natural connection with the signified. [. . .]

Language as organized thought coupled with sound

To prove that language is only a system of pure values, it is enough to consider the two elements involved in its functioning: ideas and sounds.

Psychologically our thought – apart from its expression in words – is only a shapeless and indistinct mass. Philosophers and linguists have always agreed in recognizing that without the help of signs we would be unable to make a clear-cut, consistent distinction between two ideas. Without language, thought is a vague, uncharted nebula. There are no pre-existing ideas, and nothing is distinct before the appearance of language.

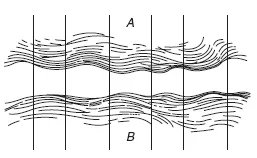

Against the floating realm of thought, would sounds by themselves yield predelimited entries? No more so than ideas. Phonic substance is neither more fixed nor more rigid than thought; it is not a mold into which thought must of necessity fit but a plastic substance divided in turn into distinct parts to furnish the signifiers needed by thought. The linguistic fact can therefore be pictured in its totality – i.e. language – as a series of contiguous subdivisions marked off on both the indefinite plane of jumbled ideas (A) and the equally vague plane of sounds (B). Figure 3 gives a rough idea of it. The characteristic role of language with respect to thought is not to create a material phonic means for expressing ideas but to serve as a link between thought and sound, under conditions that of necessity bring about the reciprocal delimitations of units. Thought, chaotic by nature, has to become ordered in the process of its decomposition. Neither are thoughts given material form nor are sounds transformed into mental entities; the somewhat mysterious fact is rather that ‘thought-sound’ implies division, and that language works out its units while taking shape between two shapeless masses. Visualize the air in contact with a sheet of water; if the atmospheric pressure changes, the surface of the water will be broken up into a series of divisions, waves; the waves resemble the union or coupling of thought with phonic substance.

Figure 3

Language might be called the domain of articulations, using the word as it was defined earlier. Each linguistic term is a member, an articulus in which an idea is fixed in a sound and a sound becomes the sign of an idea.

Language can also be compared with a sheet of paper: thought is the front and the sound the back; one cannot cut the front without cutting the back at the same time; likewise in language, one can neither divide sound from thought nor thought from sound; the division could be accomplished only abstractedly, and the result would be either pure psychology or pure phonology.

Linguistics then works in the borderland where the elements of sound and thought combine; their combination produces a form, not a substance.

These views give a better understanding of what was said before about the arbitrariness of signs. Not only are the two domains that are linked by the linguistic fact shapeless and confused, but the choice of a given slice of sound to name a given idea is completely arbitrary. If this were not true, the notion of value would be compromised, for it would include an externally imposed element. But actually values remain entirely relative, and that is why the bond between the sound and the idea is radically arbitrary.

The arbitrary nature of the sign explains in turn why the social fact alone can create a linguistic system. The community is necessary if values that owe their existence solely to usage and general acceptance are to be set up; by himself the individual is incapable of fixing a single value.

In addition, the idea of value, as defined, shows that to consider a term as simply the union of a certain sound with a certain concept is grossly misleading. To define it in this way would isolate the term from its system; it would mean assuming that one can start from the terms and construct the system by adding them together when, on the contrary, it is from the interdependent whole that one must start and through analysis obtain its elements. [. . .]

Linguistic value from a conceptual viewpoint

When we speak of the value of a word, we generally think first of its property of standing for an idea, and this is in fact one side of linguistic value. But if this is true, how does value differ from signification? Might the two words be synonyms? I think not, although it is easy to confuse them, since the confusion results not so much from their similarity as from the subtlety of the distinction that they mark.

From a conceptual viewpoint, value is doubtless one element in signification, and it is difficult to see how signification can be dependent upon value and still be distinct from it. But we must clear up the issue or risk reducing language to a simple naming-process.

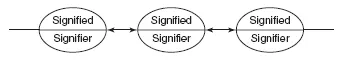

Let us first take signification as it is generally understood and as it was pictured in Figure 2. As the arrows in the drawing show, it is only the counterpart of the sound-image. Everything that occurs concerns only the sound-image and the concept when we look upon the word as independent and self-contained (Figure 4). But here is the paradox: on the one hand the concept seems to be the counterpart of the sound-image, and on the other hand the sign itself is in turn the counterpart of the other signs of language.

Figure 4

Language is a system of interdependent terms in which the value of each term results solely from the simultaneous presence of the others, as in Figure 5. How, then, can value be confused with signification, i.e. the counterpart of the sound-image? It seems impossible to liken the relations represented here by horizontal arrows to those represented above by vertical arrows. Putting it another way – and again taking up the example of the sheet of paper that is cut in two – it is clear that the observable relation between the different pieces A, B, C, D, etc., is distinct from the relation between the front and back of the same piece as in A/A′, B/B′, etc.

Figure 5

To resolve the issue, let us observe from the outset that even outside language all values are apparently governed by the same paradoxical principle. They are always composed:

- of a dissimilar thing that can be exchanged for the thing of which the value is to be determined; and

- of similar things that can be compared with the thing of which the value is to be determined.

Both factors are necessary for the existence of a value. To determine what a five-franc piece is worth one must therefore know: (1) that it can be exchanged for a fixed quantity of a different thing, e.g. bread; and (2) that it can be compared with a similar value of the same system, e.g. a one-franc piece, or with coins of another system (a dollar, etc.). In the same way a word can be exchanged for something dissimilar, an idea; besides, it can be compared with something of the same nature, another word. Its value is therefore not fixed so long as one simply states that it can be ‘exchanged’ for a given concept, i.e. that it has this or that signification: one must also compare it with similar values, with other words that stand in opposition to it. Its content is really fixed only by the concurrence of everything that exists outside it. Being part of a system, it is endowed not only with a signification but also and especially with a value, and this is something quite different. [. . .]

The sign considered in its totality

Everything that has been said up to this point boils down to this: in language there are only differences. Even more important: a difference generally implies positive terms between which the difference is set up; but in language there are only differences without positive terms. Whether we take the signified or the signifier, language has neither ideas nor sounds that existed before the linguistic system, but only conceptual and phonic differences that have issued from the system. The idea or phonic substance that a sign contains is of less importance than the other signs that surround it...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part one: Decoding the artefact

- Part two: The politics of performance

- Part three: Performing gender and sexual identity

- Part four: Performing ethnicity

- Part five: The performing body

- Part six: The space of performance

- Part seven: Spectator and audience

- Part eight: At the borders of performance

- Part nine: Analysing performance

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Performance Analysis by Colin Counsell, Laurie Wolf, Colin Counsell,Laurie Wolf in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.