eBook - ePub

Feline Infectious Diseases

Self-Assessment Color Review

Katrin Hartmann, Julie Levy

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Feline Infectious Diseases

Self-Assessment Color Review

Katrin Hartmann, Julie Levy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book covers all types of feline infectious diseases, including infections caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungi. 199 clinical cases are presented randomly, as in practice, but the wide range of cases cover infectious diseases which affect all the organ systems of the cat. The illustrated clinical cases contain integrated questions a

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Feline Infectious Diseases an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Feline Infectious Diseases by Katrin Hartmann, Julie Levy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Veterinary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Self-Assessment Color Review: Feline Infectious Diseases

1, 2: Questions

1 A 4-year-old castrated male domestic shorthair cat was seen because of a 7-day history of rigidity of the left thoracic limb (1). Sometimes, episodes of severe muscle spasm were superimposed. Forelimb rigidity had developed over a 72-hour period, but was subsequently nonprogressive. Otherwise, the cat had seemed quite well. It was eating and drinking normally, and could move around the house. Apart from the affected limb, the general physical and neurologic examinations were unremarkable. There was a small scab below the left elbow. The limb had markedly increased muscle tone and an increased triceps reflex, and there was normal sensation in the left front paw.

i. What are the differential diagnoses?

ii. What additional evaluation is indicated?

iii. Are radiographs of the spine and a myelogram likely to be helpful in this situation?

iv. Are electrodiagnostic studies likely to be useful?

2 A 2-year-old castrated male domestic shorthaired cat (2) was seen because of acute vomiting for 3 days. The cat had been obtained from a shelter 1 month previously and lived both indoors and outdoors. At presentation, the only preventative care the cat had received was one vaccination against rabies. Physical examination revealed depression, lethargy, hypersalivation, about 7% dehydration and pain on abdominal palpation. The body temperature was 40.9°C.

Blood profile | Results |

RBC | 10.4 × 1012/l |

Platelets | 156 × 109/l |

WBC | 0.40 × 109/l |

Mature neutrophils | 0.12 × 109/l |

Lymphocytes | 0.12 × 109/l |

i. What is the most likely diagnosis in this cat?

ii. What tests should be done next?

1, 2: Answers

1 i. The only likely diagnosis in a cat with this presentation is localized (or local) tetanus.

ii. Local tetanus is a clinical diagnosis, and tetanus is the only infectious disease that is usually diagnosed just based on the clinical findings. In most cases, there is insufficient tetanus toxin present in the circulation for mouse inoculation studies. In early cases it may be possible to culture Clostridium tetani from the wound using meticulous anerobic culture techniques. The presence of a wound also lends strong support to a diagnosis of local tetanus, but not all affected animals have a detectable wound. Localized tetanus occurs in cases of minimal toxin elaboration, such that when the toxin is transported retrograde up the peripheral nerves, there is only enough to interfere with inhibitory neurotransmitter release in the motor neuron pools of the affected limb.

iii. Radiographs of the spine and myelography are unlikely to provide any useful diagnostic information in this cat.

iv. Electromyography shows persistent motor unit discharges even under deep anesthesia, confirming the clinical observation of increased activity in motor nerve axons subserving the affected limb, but is usually not necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

2 i. In young animals with inadequate vaccination and worming histories, the most common causes of gastrointestinal disease are: (1) infectious, (2) parasitic, and (3) dietary (food intolerance, ingestion of noxious substances and gastrointestinal foreign bodies).

In this young cat with fever and severe leukopenia, feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) infection is the most likely differential diagnosis. The presence of a fever and leukopenia make inflammatory bowel disease unlikely. A foreign body and peritonitis should also be considered, but peritonitis seems less likely in the absence of an inflammatory leukogram. Extra-gastrointestinal disorders are less likely in a young previously healthy animal and could be ruled out with a serum biochemical panel.

ii. Further tests should include: (1) testing for FPV (fecal antigen test), and (2) fecal examination (flotation, direct smear).

If the FPV antigen test is negative, abdominal imaging studies could be performed. A serum biochemical profile is indicated to rule out metabolic causes of vomiting and to guide fluid therapy. Fecal antigen testing for giardiasis and culture for salmonellosis should be considered. An upper gastrointestinal radiographic contrast study should be considered only if foreign body or mechanical obstruction is strongly suspected. However, this carries a risk of vomiting and aspiration. Biopsy (via upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or exploratory laparotomy) should only be considered if the cat does not respond to medical care.

3, 4: Questions

3 Case 3 is the same cat as case 2. A fecal antigen test for parvovirus is negative (3).

i. Does this rule out FPV infection?

ii. What causes feline parvovirosis and how else may it be diagnosed?

4 A 7-year-old spayed female domestic shorthair cat was seen because of a 3-month history of chronic mucopurulent nasal discharge (4). The cat had received two 10-day courses of antibiotics (amoxicillin and enrofloxacin). During antibiotic treatment nasal discharge became less severe, but it relapsed afterwards. A sample of the nasal discharge had been submitted for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing, and heavy growth of Pasteurella multocida was found. Sensitivity testing indicated resistance to amoxicillin and cephalexin. The cat lived indoors, and vaccines were current. Besides the clinical signs related to the nose, the cat was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed purulent nasal discharge from both nares, a slight inspiratory nasal stridor, and slightly enlarged mandibular lymph nodes.

i. What is the most likely reason for nasal discharge?

ii. How useful is a bacterial culture of nasal discharge?

iii. What further tests could be performed?

iv. What are the possible treatment options?

3, 4: Answers

3 i. A negative fecal antigen test result does not rule out FPV infection. Viral shedding is brief and intermittent, and negative results may occur if the test is performed after more than 5–7 days of illness. Viremia occurs before fecal shedding, but negative results are also possible if fecal antigen tests are performed early during clinical illness (e.g. before the onset of diarrhea). Also, positive results are possible following MLV vaccination in healthy animals.

ii. Cats may be infected by FPV or canine parvoviruses (CPV-2a and CPV-2b). Both may cause clinical signs of panleukopenia. Kits that test for fecal canine parvovirus antigen may detect both wild and vaccine strains of both viruses. PCR testing of blood or bone marrow during early infection (viremic phase) may be positive for FPV prior to fecal antigen tests. Parvoviral infection may also be diagnosed via fecal electron microscopy, virus isolation, or immunofluorescence staining. Histopathologic examination and immunofluorescence testing are usually carried out in animals that have died. Intestinal biopsies are rarely obtained in acute parvoviral gastroenteritis, as cats are not stable enough to undergo biopsy initially, and later recover with supportive care. Antibody tests are usually negative when the animals are presented, due to the short incubation period. In this case, parvovirus infection was diagnosed by electron microscopy. The cat was treated symptomatically and recovered within a week.

4 i. Diseases that have to be considered are: (1) neoplasia, (2) lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis, (3) trauma, (4) foreign body, (5) dental problems, (6) nasopharyngeal polyps, (7) infectious diseases (e.g. FHV, FCV, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis), and (8) secondary bacterial infections.

ii. Bacterial cultures of nasal discharge are not helpful in establishing a diagnosis. Multiple bacterial organisms can be cultured from the nose of healthy cats; these usually cause secondary infection in chronic nasal diseases. To treat the problem successfully, diagnosis and treatment of the underlying primary disease should be attempted.

iii. The oral cavity should be examined for signs of dental disease, masses deviating the hard or soft palate, or polyps protruding into the nasopharynx. A complete blood count, biochemistry profile, and urinalysis should be performed to detect systemic disease causing immunosuppression or organ dysfunction. Nasal cytology could be performed to look for Cryptococcus spp., and a cryptococcal antigen titer could be obtained. To localize the disease process, involvement of the lower airways and sinuses should be investigated. CT or radiographs of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses should be followed by rhinoscopy to visualize the disease process and to obtain biopsy samples for histopathology and fungal culture.

iv. Firstly, the underlying disease process should be addressed. If this problem can be treated, secondary bacterial infection should resolve with a broad-spectrum antibiotic given for 2–3 weeks. If the underlying problem cannot be treated successfully, antibiotic pulse therapy or long-term treatment with an antibiotic may be helpful.

5, 6: Questions

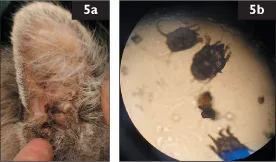

5 A 3-year-old spayed female domestic shorthair cat was seen because of scratching her ears and shaking her head. On physical examination, brown crusty debris was seen in both ears (5a). There were excoriations of the skin behind one ear and miliary dermatitis in the dorsal lumbosacral area, as well as extensive excoriation on the ventral aspect of the neck. An organism was seen on microscopic examination (5b).

i. What is the organism shown in the image?

ii. How is it transmitted?

iii. Is this organism specific to cats?

iv. How should the cat be treated?

v. Is the miliary dermatitis related to this organism?

6 A 7-year-old spayed female domestic shorthair cat was seen because of an acute onset of left-sided head tilt and Horner’s syndrome (6) 5 days ago. The cat lived indoors and outdoors. It had been vaccinated against FPV, FHV and FCV. It had a lifelong history of chronic nasal discharge and was treated intermittently with antibiotics; the last treatment was 6 months previously. On examination, there was mucopurulent nasal ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Self-Assessment Color Review: Feline Infectious Diseases

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Editor and contributor profiles

- Classification of cases

- Abbreviations

- Self-Assessment Color Review: Feline Infectious Diseases

- Table of reference ranges

- Index