eBook - ePub

Spelling, Handwriting and Dyslexia

Overcoming Barriers to Learning

Diane Montgomery

This is a test

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Spelling, Handwriting and Dyslexia

Overcoming Barriers to Learning

Diane Montgomery

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This ground-breaking book argues that spelling and writing need to be given more consideration in teaching and remedial settings especially if dyslexic pupils are to be helped back up to grade level, and other pupils are to make more effective, quicker progress. Helping teachers and student-teachers to understand the valuable contribution spelling and handwriting makes to literacy development in primary and secondary schools, this book shows them how to overcome existing barriers to learning. Chapters cover key topics such as:

- the nature of spelling and the impact of the National Literacy Strategy

- the strengths and weaknesses of existing schemes for handwriting

- the definitions of dyslexia and how common spelling errors by dyslexics are made

- making effective links between strategic assessment and strategic interventions in schools

- problem-based learning, underpinned by plenty of casestudies and real life classroom examples.

Written by a well-known author in the field of literacy and dyslexia, this is a core text that will interest teachers, teacher educators, and undergraduate and postgraduate students in education and inclusion.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Spelling, Handwriting and Dyslexia by Diane Montgomery in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Bildung & Bildung Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Introduction

Introduction

The first three chapters in this book examine the nature of spelling, handwriting and dyslexia and their relationship to becoming literate and to each other. The key theme which links them is how can an understanding of each of them help us design and develop interventions which will work better and faster so that children become literate more easily and earlier. In the meantime we have to recognise that some will take more time and effort and we need to cater for this.

Teachers are daily confronted with the problem of deciding if, for those with slowly developing or poor literacy skills, they should:

- teach to strengths or weaknesses?

- make compensatory or remedial provision or both?

- take account of learning styles?

- offer individual or small group provision?

Each response has had a period when it has been in fashion, and cost has had a significant influence. Training and trainers have to deal with these issues and too often advice has occurred in a piecemeal fashion such as how to develop worksheets for the less literate, how to cater for different learning styles, if indeed they exist (Coffield 2005), and whether ‘mind mapping’, visual training or neurolinguistic programming will make a difference.

Looking at the needs of underachievers across the ability range we find that their major areas of difficulty lie in an inability to cope with all the written work that schools require them to do. Whatever the reasons for their difficulties there are enough of such pupils for us to thoroughly review the general teaching and learning needs of children. This has led me in a number of researches and publications to propose that education in schools is over didactic and teacher dominated, a methodology which has been promoted by successive governments and their agencies. It involves much teacher talk and pupil writing but these forms of teaching and learning need to be questioned for efficacy with school pupils.

Although the ultimate aim of education may well be to develop the potential of each individual to the full, simply telling children information and practising responses is not the only way to do this. My view of a ‘good’ education is one which enables children to think efficiently and to communicate those thoughts succinctly in whatever subject area is under consideration and whatever the age the pupil.

To promote such learning objectives modest changes in the curriculum are needed. By this I mean that we should reframe the provision in mainstream education by developing in every curriculum subject: a cognitive curriculum; a talking curriculum; a positive supportive behaviour policy; and a developmental writing and recording policy. These would not involve a change in curriculum content but small changes in the ways in which we teach it and the ways in which we enable children to learn.

The cognitive curriculum

This consists of:

- developmental positive cognitive intervention (PCI, see below)

- cognitively challenging questioning – open and problem posing

- deliberate teaching of thinking skills and protocols

- reflective teaching and learning

- creativity training

- cognitive process teaching methods e.g. cognitive study and research skills, investigative learning and real problem solving, experiential learning, games and simulations, language experience approaches, collaborative learning.

What was clear from using these methods was that intrinsic motivation was developed and children’s time on–task extended in their enjoyment long after the lessons ended. Disaffected children remained at school and more able students recorded such things as ‘This is much better than the usual boring stuff we get’. They all began to spend extended periods of time on, instead of off–task. The quality of their work frequently exceeded all expectations, as did that of the most modest of learners and there were sometimes the most surprisingly interesting and creative responses from unsuspected sources. The collaborative nature of many of the tasks meant that mixed ability groups could easily access the work and all could be included in the same tasks with no diminution of the achievements of any.

The talking curriculum

This is intimately related to the cognitive curriculum. It consists of the following techniques:

- TPS think – pair – share

- circle time

- small group work

- group problem solving

- collaborative learning

- reciprocal teaching

- peer tutoring

- thinkback (Lockhead 2001)

- role play, games and drama

- debates and ‘book clubs’ (Godinho and Clements 2002)

- presentations and ‘teach-ins’

- poster presentations

- exhibitions and demonstrations

- organised meetings.

Underachievers in particular need to talk things through before they are set to writing them down. In fact all young learners need such opportunities for often we do not know what we think until we try to explain it to someone else. Where such children come from disadvantaged cultural and linguistic environments the talking approaches are essential. This not only helps vocabulary learning and comprehension but also develops organisational skills in composition. To support the organisational abilities, direct teaching of ‘scaffolds’ can be especially helpful and is the logical extension of the developmental writing curriculum.

When the talking approach to the cognitive curriculum was used with pupils, their feedback showed that enjoyment and legitimised social interaction were not often connected in their minds with school learning. This meant that at each stage they had to be shown in explicit ways that this was real school work, how much they had learned and how their work was improving. This was done by giving detailed comments on their work and their learning processes, both verbally and in writing, couched in constructive terms.

A positive approach to behaviour management in classrooms

Positive behaviour management and classroom control were extensively researched in the observation and feedback to teachers in over 1250 lessons. During this research four interrelated strategies for improving teaching and reducing behaviour problems were evolved, as described below.

C.B.G: ‘Catch them being good’

The C.B.G. strategy requires that the teacher positively reinforces any pupil’s correct social and on-task responses with nods, smiles, and by paraphrasing correct responses and statements and supporting their on-task academic responses with such phrases as, ‘Yes, good’ and ‘Well done’. Incorrect responses should not be negated but the pupil should be encouraged to have another try, or watch a model, and the teacher prompts with, ‘Yes, nearly’, ‘Yes, and what else ...’, and ‘Good so far, can anyone help [him or her] out?’ and so on.

3 Ms: management, monitoring and maintenance

The 3Ms represent a series of tactics which effective teachers use to gain and maintain pupils’ attention whatever teaching method or style they subsequently use. When teachers with classroom management disciplining problems were taught to use these strategies in observation and feedback sessions they became effective teachers.

PCI: positive cognitive intervention

During the steady move round the room the teacher should look at the work with the pupil and offer developmental PCI advice in which a positive statement about progress thus far is made and then ideas and suggestions for extension are offered. Alternatively, through constructive questioning the pupils are helped to see how to make the work better or achieve the goals they have set themselves. When the work has been completed again there should be further written or spoken constructive and positive comments and further ideas suggested.

Tactical lesson planning (TLP)

Lesson plans need to be structured into timed phases for pupil learning not teacher talk; e.g. title/lesson objective or focus; introduction (teacher talk, Q/A); phase 1 (pupils reading); phase 2 (pupils doing practical work); phase 3 (pupils speaking – sharing experiences); phase 4 (pupils writing and recording work and ideas); concluding activity (Q/A reporting back to the class). Getting the TLP right improves the pace of the lesson and increases pupil time on-task.

A developmental writing and recording policy

Writing and recording are not the same. Recording may take place in writing or in a range of other forms such as cartoons, maps, diagrams, pictures, videos and audio tapes. Each of these options should be available at some point in the curriculum as well as considering if recording is needed at all. For example, why should every subject require pupils to write their own textbooks? Are there better methods of learning and consolidation?

The rest of this book will offer an analysis of writing and writing difficulties, because these seem to be a neglected area of study, and so that a developmental writing policy may be developed. The evidence and the methods associated with the above may be found in the following books by the author: Reversing Lower Attainment (2003); Able Underachievers (2000a); and Helping Teachers Develop through Classroom Observation (2002).

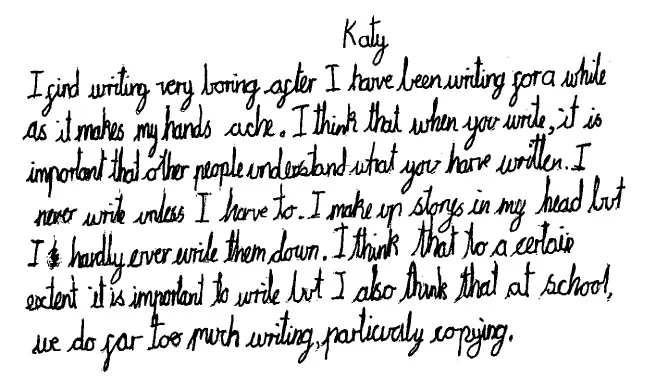

Figure 0.1 Views on writing of Katy, aged seven

Chapter 1

Spelling

Learning and teaching

Introduction

At the simplest level, spelling is the association of alphabetic symbols called graphemes with speech sounds called phonemes, the smallest identifiable sounds in speech. In English we use 44 distinct phonemes out of a possible 70 or so including clicks which have been identified in human speech worldwide. The association of speech sounds with the alphabet symbols is called ‘sound–symbol correspondence’ or systematic ‘phonics’. Phonics permits simple regular spellings such as d-o-g for ‘dog’, and b-e-d for ‘bed’ and so on. It is thought that when the alphabet was first invented several centuries BC, most words could be transcribed thus, but over time this simple correspondence between sound and symbol called one-to-one correspondence has, in many languages, gradually slipped. In this respect Turkish and Italian are more regular than Greek which is more regular than English. In earlier centuries English was more ‘regular’ but this correspondence slipped for a variety of reasons, some of which will have been the ‘freezing’ of the spelling convention at the time of the introduction of the printing press and then again following the publication of Johnson’s dictionary of the English language in the eighteenth century, plus the nature of English itself.

In addition, pronunciation and dialects of the English speaking peoples have changed and developed over time. For example the words ‘class’, ‘path’ and ‘bath’ are now pronounced with a longer ‘a’ sound as in ‘clarss’, ‘parth’ and ‘barth’ in the southern counties of England whilst in the North the older, original form with the short vowel sound is preserved. This also makes it easier for beginning spellers in the North to spell the word correctly without the intrusive ‘r’.

Before the Puritans were forced to leave the country to settle in America we must have pronounced words such as ‘shone’ with the long vowel sound. Now we only hear this form in certain North American dialects and here in England we say ‘shon’. They also tend to preserve the old form of ‘dove’ for ‘dived’ just as you may occasionally still hear ‘dove’, ‘snew’ for snowed, and ‘tret’ for treated in East Anglia. It has become necessary for all members of a modern society to become able to communicate in writing by committing spelling patterns to paper or screen. This is a more difficult task than recognising all the letters when they are present in context in a book. Spelling requires the recall of spellings from the memory in exactly the correct order or the construction of such spellings if they are not already stored in the word memory store or lexicon.

A controversy exists between most teachers and researchers who contend that spelling is a natural extension of reading and others such as Chomsky (1971) and Clay (1975, 1989), who argue that writing is a more concrete task, and developmentally occurs first. Nevertheless, agreement does exist that spelling is a more difficult task than reading (Frith 1980; Mastropieri and Scruggs 1995). ‘It requires production of an exact sequence of letters, offers no contextual clues, and requires greater numbers of grapheme-to-phoneme decisions’ (Fulk and Stormont-Spurgin 1995: 488).

Prior to the introduction of the printing press and even for some while afterwards spelling by scribes and clerks was much more variable than it is now and such variations were accepted. Today only correct spelling is acceptable and poor spelling is regarded, often quite wrongly, as indicative of poor intellectual ability or carelessness and such applicants for jobs are often screened out. Word processor spell checkers can now be used to conceal most poor spelling but as soon as we send emails or handwrite notes and exam essays it is revealed. Employers now often insist on job applications being handwritten to discover spelling difficulties and other personal characteristics.

English spelling also reflects its complex history, making it more difficult than many other languages to spell. Our modern alphabet has only 26 letters to accommodate the 44 English phonemes. Thus double vowels (r-oa-d, b-ea-d), diphthongs (r-ou-nd; c-ow) and six consonant digraphs (ch-, sh-, ph-, wh- and th- (voiced and unvoiced)) supplement them to preserve sound–symbol correspondence with graphemes.

In English, morphemes are also as significant as phonemes and the language itself can be said to be morphological in structure. Morphemes such as cat, -ing, I, a, -ed are the smallest elements of meaningful speech sound and can be single letters which when in isolation or added to a word are meaningful or change the meaning. There is thus a conflict between phonemic representation – writing the spoken language directly as it sounds now – and morphemics – representing the meaning and often the historical origins of the language, showing where the words have come from and how they sounded then. It is the convention in English to preserve the history over the current sound, thus sheep herder is spelt as shepherd rather than sheperd or shepperd. In the evolution of this spelling we may have pronounced sheep as shep, or we may have transcribed sheep as shep as some poor or beginning spellers might today.

English spelling is rich in history of this kind and so methods of teaching which offer an understanding of both the origins of the language through morphemics as well as its phonemic structure are important; however, they are rare.

The origins of the alphabet writing system

Writing systems first appeared about the same time some 5000 years ago in several different locations: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Hyrapus in Pakistan, and China. These writing systems evolved throughout history ranging from hieroglyphs – sacred characters used in ancient Egyptian picture writing and picture writing in general, to logographs – the use of single signs or symbols in Chinese representing words, to syllabaries – a set of characters representing syllables, to rebus – an enigmatic representation of a word or part of a word by pictures. It is maintained however that the alphabet system was only ever invented once (Delpire and Monory 1962; Gelb 1963).

Phoenician traders were believed to have invented the first alphabet in about the seventh century BC for their commercial needs as a maritime trading nation. The Greeks are thought to have experimented with its use and added vowel symbols to adapt it to their Indo-European language, and by the fourth century BC a common Hellenic alphabet and language were constructed. The Romans appeared to have acquired this alphabet from the Greeks (Delpire and Monory 1962) and disseminated it through their conquests to the Roman Empire. The medieval Christians then added the definitive distinction between ‘i’ and ‘j’ and ‘u’ and ‘v’.

What is of interest and significance is that the alphabet was only invented once, presumably by some stroke of genius. A second important feature in its developm...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Foreword

- Part 1 Introduction

- Part II Intervention Techniques

- Appendix

- Epilogue

- References