![]()

1

The Challenge of Reforming Policy on Services

Trade policy used to be about tariffs—whether to raise them or to lower them. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when government involvement in the economy was minimal, the purpose of the tariff was either to raise revenuex or to further strategic and mercantilist objectives. Once economists were convinced that free trade was the optimum policy, it became relatively easy to prescribe the appropriate course of action. Governments were advised to reduce their tariffs and allow goods to be traded unobstructedly.

Trade policy today has little to do with tariffs. For one thing, most tariffs have been either reduced or bound as a result of successive rounds of multilateral trade negotiations under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). For another, governments have been ingenious in devising new policy measures for discriminating in favour of their own national firms. Their motives for intervention in the economy have also multiplied. Most unsettling for the old prescription of free trade, there are now many theoretically sound reasons why governments may have to intervene to restrict trade.

The process by which trade policy is determined in most western countries is much more complex today than it used to be only a few decades ago. Because governments have assumed a more active role in managing their own economies, they also have to monitor and assess the ever-increasing interaction among economies, especially because foreign and domestic public policies have a significant effect on trade. Not only is this interaction intensifying, but it is also diversifying. Of course, international exchange has never been only about goods. Movement of capital and people has always been an essential part of entrepreneurial and colonial commerce. Since capital and people offer services, trade in services is not a new phenomenon. What makes it qualitatively new is the way in which it is taking place. Physical movement by capital or people is rapidly being displaced by other forms of trade. Technological progress is making possible the trade of services without those who provide them or those who consume them ever having to leave their countries. Technological advancement is also making possible the provision of new and more sophisticated services which were unavailable only a few years ago (e.g. simultaneous dealing of shares in different stock exchanges).

Many governments are now actively considering how to respond to the increasing amount and diversity of services that cross their borders. And they have to reconsider their policy on services because services are an essential component of any economic activity. Their importance has been obscured by the fact that the term ‘services’ comprises many, very diverse activities. Chapter 2 reviews the various meanings and definitions of the term and proposes a way of looking at services which can help in understanding the problems of liberalizing trade in services.

An aspect of services which has prompted governments to begin reconsidering their policy is the variety of ways by which services can be traded. Despite technological advancement, some services can be supplied only through personal contact between the client and the person who performs the service. Satellite television may provide you with entertainment from any place on earth but you still have to visit your barber or hairdresser. Movement of either the provider or the client may, therefore, be necessary. But, if the provider moves to another country, can this movement still be classified as trade or is it an act of foreign investment? Chapter 3 uses the definition proposed in Chapter 2 to examine the extent to which trade of services can be logically differentiated from investment. It is argued that there is no need to distinguish between the two if the purpose is to facilitate transactions in services between residents and foreigners. The mode of transaction should not be a cause for preventing that transaction from taking place.

Yet many governments obstruct such transactions on the grounds that foreigners offer services of allegedly lower quality than that expected from domestic providers. Trade is tightly controlled in the name of consumer protection. This objective does not necessarily mean that the invisible hand of the market should be amputated. But regulation to protect consumers is often used as a pretext to justify measures that reduce competition and exclude foreign firms from domestic markets. Chapter 4 examines how a distinction can be made between legitimate, or appropriate, regulations and discriminatory regulations that prevent foreign firms from operating in domestic markets. That chapter also defines, in broad terms, the ‘zero-tariff equivalent’ for services: i.e. the yardstick by which ‘free’ trade in services can be measured.

This paper concentrates primarily on restrictions on foreign service-providers, rather than on the appropriate level or strictness of regulation in a market, since its main objective is to examine how discriminatory policies against foreign providers can be identified and eliminated. Nevertheless, as explained in Chapter 4, elimination of trade barriers may also have to be accompanied by some relaxation of the strictness of regulatory control or some modification of the method by which regulation is administered. The invisible hand could work better if regulators were a little less visible.

The problem of distinguishing between appropriate and discriminatory regulation has been one of the chief difficulties encountered by countries which have been attempting to open up their trade either unilaterally or multilaterally. Chapter 5 reviews the experience of the European Community (EC) as it proceeds towards unification of its internal market by 1992. The Community’s experience highlights the difficulty of removing trade impediments which are deeply embedded in a country’s economic system and institutions. The EC was faced with two polar options. Either it could replace national regulations with Community regulations, or it could allow member countries to retain their own, and in many respects disparate, regulations. In the event, it has chosen a combination of these two opposites. The process of harmonizing all the diverse national rules would have been interminable and very acrimonious. On the other hand, liberalization without some harmonization would have resulted in ‘competition among rules’. Each member country would have an incentive to adjust its own rules to attract footloose service industries by undercutting the rules of other countries.

The question which arises is whether the EC’s approach of a mixture of harmonization and liberalization can be successfully replicated by other countries. Chapter 6, which examines the progress of the current GATT negotiations on services, suggests that GATT cannot realistically be expected to adopt the EC’s model. GATT lacks the political cohesion and the institutions to implement that model effectively. Because it is unlikely that all GATT members will sign an agreement on services, it becomes imperative that an eventual agreement is prevented from degenerating into an exclusive club of a few countries. At the same time, however, a country would have an incentive to join that agreement only if it cannot derive the benefits while remaining outside it. Therefore, given that membership of the agreement is unlikely to be universal, the challenge for GATT is to encourage membership while preventing the agreement from becoming an exclusive club that undermines the multilateral foundation of the postwar trading system.

The treatment of non-members is not the only challenge. Another, already divisive, issue is the treatment of members who would demand special status. Many developing countries have opposed a GATT agreement on services. But, to the extent that they might concede to such an agreement, they have made it clear that they expect ‘special and differential’ treatment. Chapter 7 asks what form this special and differential treatment could take.

There is one major theme that runs throughout this paper: a liberal trade policy for services requires reliance on non-discriminatory rules. As elaborated in the following chapter, services are processes which in many respects are inseparable from those who provide them and their activities. Ultimately a policy that regulates the provision of services is a set of rules on ‘who does what and how’. But safeguarding the quality of services does not necessarily imply exclusion of foreign providers. It is sufficient to require them to comply with the same rules that apply to domestic firms.

Because of the EC’s 1992 initiative and the current GATT talks on services, there has been much reference to the meaning of reciprocity in services liberalization. The only kind of reciprocal concession that makes economic sense and provides for true and irreversible liberalization is an agreement to extend to foreign firms which operate in the domestic market the same treatment as that accorded to other domestic firms: i.e. non-discriminatory application of domestic regulations. The traditional liberalizing approach of reciprocally reducing particular trade restrictions cannot be applied as effectively in services as was applied in goods. The majority of goods are treated as other national goods as soon as they are allowed to cross a country’s frontier. Since the concept of a frontier is not well defined in services, liberalization that proceeds on the basis of reciprocal concessions on particular policy measures implies that foreign service-providers would still be treated differently even after they cross a country’s physical frontier. Removal of physical border barriers would not eliminate discrimination. As long as an element of discrimination remained in the system, governments would have an incentive to change the rules in favour of their national firms even after they agree to open up their markets to foreign competition. Liberalization will take hold only if governments commit themselves to the rule of equal treatment of all firms under their jurisdiction.

Of course, it may be argued that things cannot get worse than the existing state of rife discrimination and trade obstruction. Although this view is in some respects understandable, it fails to recognize the important element of expectation of ‘fair play’ in trade diplomacy. If for some reason the process of multilateral liberalization is reversed, bilateral games of one-upmanship will almost certainly fill the void. Those countries whose expectations of forthcoming benefits are disappointed because other countries do not honour their commitments would come under pressure by domestic groups to retaliate. A series of retaliatory and counter-retaliatory moves would severely dislocate and reduce world trade. There is more at stake in a failed bid to liberalize than in continuing with existing protectionism.

![]()

2

The Nature of Services

In order to be able to study services we must know what they are. They can be defined in two ways. The first method, which is ad hoc, simply groups together certain activities and calls them services. This method would be adequate if businessmen were to stop innovating. Once firms engage in new activities there is the question of where they can be classified. It becomes necessary to define criteria for distinguishing in a consistent manner what might be a service. Hence, the second method is systematic, defining services on the basis of certain criteria.

There is another reason why the ad-hoc method is not satisfactory. There can be many possible ways of grouping together different economic activities, not all of which are equally useful. A definition is useful if it helps towards better understanding of the effects, implications or consequences of what is being defined. The objective of this chapter is to define services in a systematic and useful way. For the purpose of this study, a useful way is one which helps us to understand how trade in services may be liberalized and how services may be regulated if need be.

The chapter reviews the various definitions of services that have been proposed and also examines how services are measured and classified in national accounting systems. There exists no precise method for measuring services. In consequence, the traditional approach to trade liberalization, which matches concessions of equivalent magnitude, is unlikely to be appropriate for services. Moreover, if, as suggested in this chapter, services are activities or processes, then a more suitable method of liberalization would involve the adoption of rules that apply to the operations of service-providers. The exchange of equivalent concessions would be more relevant for goods, which can be more easily identified.

Defining Services

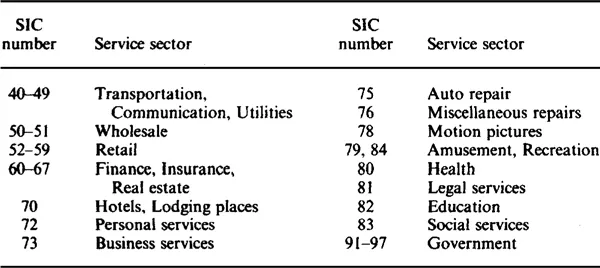

In a paradoxical way, the more intensively services are studied, the less certainty there is about how they can be defined and classified. According to Gershuny and Miles (1983), the term ‘services’ has four distinct uses. It may refer to industry (the firms that produce services), products (which are not exclusively produced by service firms), occupations (classification of labour markets) or functions (classification of activities). This chapter reviews the various definitions of the term services as used to describe particular functions or activities. Table 2.1 shows those economic activities which are classified as services in national accounting systems.

Most definitions attempt to convey the essence of services by identifying how they differ from goods, which, in this respect, provide a benchmark. By using goods as a benchmark of comparison, these definitions are systematic but, as argued below, they are not very useful because they do not explain what purpose they serve by perceiving services as something different from goods. Goods are defined as ‘tangible’, ‘visible’ and ‘storable’ or ‘permanent’. Conversely, services are defined as ‘intangible’, ‘invisible’ and ‘non-storable’ or ‘transient’. Goods can be exchanged, whereas services are produced by one economic agent for another and are consumed simultaneously with production. (For an exhaustive review of definitions of services, see Feketekuty, 1988.)

Table 2.1 The Standard Industrial Classification (SIC)

Source: Singelmann (1978).

These features, however, cannot describe all of what are conventionally understood as services. For example, insurance is intangible and invisible but is not transient. A haircut is visible and does have some permanence, whereas a live musical performance is also visible but transient. Definitions which are based on the characteristics of intangibility and transience seem to obscure rather than clarify the meaning of services.

This problem arises partly because these definitions do not specify what the identified characteristics refer to. Do they refer to the production (i.e. performance) of a service or to its output (i.e. intended effects)? The act of performing a service may be temporary but the effects need not be. For example, some professors claim that their lectures have lifelong effects on their students.

An adequate definition must, inter alia, make a distinction between the process of production and the product of a service. It must also clarify the meaning of ‘transience’. Does it refer to a specific length of time? Is it a relative term, simply indicating that goods are more permanent than services? But how can it accommodate the fact that a lecture, or occasionally a bank transaction, is longer than the lifetime of an ice-cream? Or does it mean that production and consumption of services must take place at the same time? As argued later, not only is this ‘simultaneity’ requirement not applicable to many services (e.g. pension management, investment analysis) but it also depends on the way the intended output of a service is given to consumers (e.g. one may ‘consume’ a doctor’s prescription at one’s discretion).

In attempting to differentiate between the performance and effects of services, Hill (1977, p. 318) has defined a service as ‘a change in the condition of a person, or of a good belonging to some economic unit, which is brought about as the result of the activity of some other economic unit, with prior agreement of the former person or economic unit’. A haircut is certainly a service. But how should insurance or investment advice be classified? When insurance brokers write a policy, the last thing they want is for the policy to induce a change in the condition or behaviour of the insured person. Is insurance a service only after a claim is filed? In the case of any kind of professional advice there need not be any automatic change in the condition of anybody. Professional consultation may actually result in no change, or may be intended to prevent change.

The term ‘change’ requires clarification. By emphasizing ‘change’, which is the end-result or effect of a service, Hill’s definition cannot really distinguish between services, goods and other effects of economic activities. The acquisition of a good does change somebody’s endowment. Intuitively we know that a good is an object, whereas a service is a process. A definition of services, therefore, should focus on the process aspect of a service rather than its effect.

According to Riddle (1986), ‘services are economic activities that provide time, place and form utility while bringing about a change in or for the recipient of the service. Services are produced by (a) the producer acting for the recipient; (b) the recipient providing part of the labour; and/or (c) the recipient and the producer creating the service in interaction’. Riddle’s definition is more comprehensive than others. It accounts for the time element in the intended or expected effects of services. It also recognizes that many services are ‘co-produced’ by the provider and the client. A management consultant, for example, would hardly be able to provide a service unless he/she were guided with respect to the client’s intentions, strengths and weaknesses. A lesson would hardly be worth having unless the student (or client) made an effort together with the instructor (or provider).

It is interesting to note how definitions of s...