![]() Part I

Part I

Who’s Afraid of Mr Jinnah?![]()

CHAPTER 1

Understanding Jinnah

God cannot alter the past, but historians can.

(Samuel Butler)

Islam gave the Muslims of India a sense of identity; dynasties like the Mughals gave them territory; poets like Allama Iqbal gave them a sense of destiny. Jinnah’s towering stature derives from the fact that, by leading the Pakistan movement and creating the state of Pakistan, he gave them all three. For the Pakistanis he is simply the Quaid-i-Azam or the Great Leader. Whatever their political affiliation, they believe there is no one quite like him.

Jinnah: a life

Mohammed Ali Jinnah was born to an ordinary if comfortable household in Karachi, not far from where Islam first came to the Indian subcontinent in AD 711 in the person of the young Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim. However, Jinnah’s date of birth—25 December 1876—and place of birth are presently under academic dispute.

Just before Jinnah’s birth his father, Jinnahbhai Poonja, had moved from Gujarat to Karachi. Significantly, Jinnah’s father was born in 1857—at the end of one kind of Muslim history, with the failed uprisings in Delhi—and died in 1901 (F.Jinnah 1987:vii).

Jinnah’s family traced its descent from Iran and reflected Shia, Sunni and Ismaili influences; some of the family names—Valji, Manbai and Nathoo—were even ‘akin to Hindu names’ (F.Jinnah 1987:50). Such things mattered in a Muslim society conscious of underlining its non-Indian origins, a society where people gained status through family names such as Sayyed and Qureshi (suggesting Arab descent), Ispahani (Iran) and Durrani (Afghanistan). Another source has a different explanation of Jinnah’s origins. Mr Jinnah, according to a Pakistani author, said that his male ancestor was a Rajput from Sahiwal in the Punjab who had married into the Ismaili Khojas and settled in Kathiawar (Beg 1986:888). Although born into a Khoja (from khwaja or ‘noble’) family who were disciples of the Ismaili Aga Khan, Jinnah moved towards the Sunni sect early in life. There is evidence later, given by his relatives and associates in court, to establish that he was firmly a Sunni Muslim by the end of his life (Merchant 1990).

One of eight children, young Jinnah was educated in the Sind Madrasatul Islam and the Christian Missionary Society High School in Karachi. Shortly before he was sent to London in 1893 to join Graham’s Shipping and Trading Company, which did business with Jinnah’s father in Karachi, he was married to Emibai, a distant relative (F.Jinnah 1987:61). It could be described as a traditional Asian marriage—the groom barely 16 years old and the bride a mere child. Emibai died shortly after Jinnah left for London; Jinnah barely knew her. But another death, that of his beloved mother, devastated him (ibid.).

Jinnah asserted his independence by making two important personal decisions. Within months of his arrival he left the business firm to join Lincoln’s Inn and study law. In 1894 he changed his name by deed poll, dropping the ‘bhai’ from his surname. Not yet 20 years old, in 1896 he became the youngest Indian to pass. As a barrister, in his bearing, dress and delivery Jinnah cultivated a sense of theatre which would stand him in good stead in the future.

It has been said that Jinnah chose Lincoln’s Inn because he saw the Prophet’s name at the entrance. I went to Lincoln’s Inn looking for the name on the gate, but there is no such gate nor any names. There is, however, a gigantic mural covering one entire wall in the main dining hall of Lincoln’s Inn. Painted on it are some of the most influential lawgivers of history, like Moses and, indeed, the holy Prophet of Islam, who is shown in a green turban and green robes. A key at the bottom of the painting matches the names to the persons in the picture. Jinnah, I suspect, was not deliberately concealing the memory of his youth but recalling an association with the Inn of Court half a century after it had taken place. He had remembered there was a link, a genuine appreciation of Islam. Had those who have written about Jinnah’s recollection bothered to visit Lincoln’s Inn the mystery would have been solved. However, knowledge of the pictorial depiction of the holy Prophet would certainly spark protests; demands from the active British Muslim community for the removal of the painting would be heard in the UK.

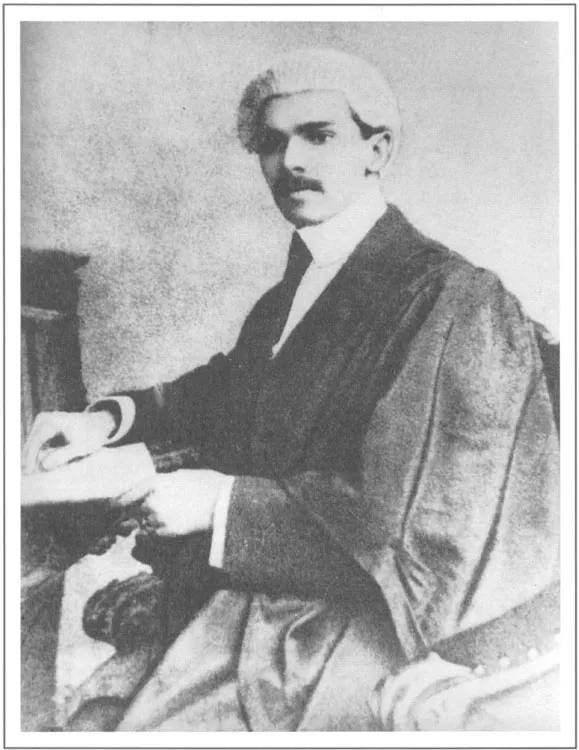

In London Jinnah had discovered a passion for nationalist politics and had assisted Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian Member of Parliament. During the campaign he became acutely aware of racial prejudice, but he returned to India to practise law at the Bombay Bar in 1896 after a brief stopover in Karachi. He was then the only Muslim barrister in Bombay (see plate 1).

Plate 1 Jinnah as a young barrister

Jinnah was a typical Indian nationalist at the turn of the century, aiming to get rid of the British from the subcontinent as fast as possible. He adopted two strategies: one was to try to operate within the British system; the other was to work for a united front of Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Parsees against the British. He succeeded to an extent in both.

Jinnah’s conduct reflected the prickly Indian expression of independence. On one occasion in Bombay, when Jinnah was arguing a case in court, the British presiding judge interrupted him several times, exclaiming, ‘Rubbish.’ Jinnah responded: ‘Your honour, nothing but rubbish has passed your mouth all morning.’ Sir Charles Ollivant, judicial member of the Bombay provincial government, was so impressed by Jinnah that in 1901 he offered him permanent employment at 1,500 rupees a month. Jinnah declined, saying he would soon earn that amount in a day. Not too long afterwards he proved himself correct.

Stories like these added to Jinnah’s reputation as an arrogant nationalist. His attitude towards the British may be explained culturally as well as temperamentally. He was not part of the cultural tradition of the United Provinces (UP) which had revolved around the imperial Mughal court based in Delhi and which smoothly transferred to the British after they moved up from Calcutta. Exaggerated courtesy, hyperbole, dissimulation, long and low bows, salaams that touched the forehead repeatedly—these marked the deference of courtiers to imperial authority. Even Sir Sayyed Ahmad Khan, one of the most illustrious champions of the Muslim renaissance in the late nineteenth century, came from a family that had served the Mughals, but had readily transferred his loyalties to the British.

Jinnah often antagonized his British superiors. Yet he was clever enough consciously to remain within the boundaries, pushing as far as he could but not allowing his opponents to penalize him on a point of law. In short he learned to use British law skilfully against the British.

At several points in his long career, Jinnah was threatened by the British with imprisonment on sedition charges for speaking in favour of Indian home rule or rights. He was frozen out by those British officials who wished their natives to be more deferential. For example, Lord Willingdon, Viceroy of India in 1931–6, did not take to him, and even the gruff but kindly Lord Wavell, Viceroy in 1943–7, was made to feel uncomfortable by Jinnah’s clear-minded advocacy of the Muslims, even though he recognized the justice of Jinnah’s arguments. The last Viceroy, however, Lord Mountbatten, could not cope with what he regarded as Jinnah’s arrogance and haughtiness, preferring the natives to be more friendly and pliant.

Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity

On his return from England in 1896, Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress. In 1906 he attended the Calcutta session as secretary to Dadabhai Naoroji, who was now president of Congress. One of his patrons and supporters, G.K.Gokhale, a distinguished Brahmin, called him ‘the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’. He was correct. When Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the Hindu nationalist, was being tried by the British on sedition charges in 1908 he asked Jinnah to represent him.

On 25 January 1910 Jinnah took his seat as the ‘Muslim member from Bombay’ on the sixty-man Legislative Council of India in Delhi. Any illusions the Viceroy, Lord Minto, may have harboured about the young Westernized lawyer as a potential ally were soon laid to rest. When Minto reprimanded Jinnah for using the words ‘harsh and cruel’ in describing the treatment of the Indians in South Africa, Jinnah replied: ‘My Lord! I should feel much inclined to use much stronger language. But I am fully aware of the constitution of this Council, and I do not wish to trespass for one single moment. But I do say that the treatment meted out to Indians is the harshest and the feeling in this country is unanimous’ (Wolpert 1984:33).

Jinnah was an active and successful member of the (mainly Hindu) Indian Congress from the start and had resisted joining the Muslim League until 1913, seven years after its foundation. None the less, Jinnah stood up for Muslim rights. In 1913, for example, he piloted the Muslim Wakfs (Trust) Bill through the Viceroy’s Legislative Council, and it won widespread praise. Muslims saw in him a heavy weight on their side. For his part, Jinnah thought the Muslim League was ‘rapidly growing into a powerful factor for the birth of a United India’ and maintained that the charge of ‘separation’ sometimes levelled at Muslims was extremely wide of the mark. On the death of his mentor, Gokhale, in 1915, Jinnah was struck with ‘sorrow and grief’ (Bolitho 1954:62), and in May 1915 he proposed that a memorial to Gokhale be constructed. A few weeks later in a letter to The Times of India he argued that the Congress and League should meet to discuss the future of India, appealing to Muslim leaders to keep pace with their Hindu ‘friends’.

Jinnah was elected president of the Lucknow Muslim League session in 1916 (from now he would be one of its main leaders, becoming president of the League itself from 1920 to 1930 and again from 1937 to 1947 until after the creation of Pakistan). Jinnah’s political philosophy was revealed in the Lucknow conference in the same year when he helped bring the Congress and the League on to one platform to agree on a common scheme of reforms. Muslims were promised 30 per cent representation in provincial councils. A common front was constructed against British imperialism. The Lucknow Pact between the two parties resulted. Presiding over the extraordinary session, he described himself as ‘a staunch Congressman’ who had ‘no love for sectarian cries’ (Afzal 1966:56–62).

This was the high point of his career as ambassador of the two communities and the closest the Congress and the Muslim League came. About this time, he fell in love with a Parsee girl, Rattanbai (Ruttie) Petit, known as ‘the flower of Bombay’. Sir Dinshaw Petit, her father and a successful businessman, was furious, since Jinnah was not only of a different faith but more than twice her age, and he refused his consent to the marriage. As Ruttie was under-age, she and Jinnah waited until she was 18, in 1918, and then got married. Shortly before the ceremony Ruttie converted to Islam. In 1919 their daughter Dina was born.

By this time even the British recognized Jinnah’s abilities. Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, wrote of him in 1917: ‘Jinnah is a very clever man, and it is, of course, an outrage that such a man should have no chance of running the affairs of his own country’ (Sayeed 1968:86).

Jinnah cut a handsome figure at this time, as described in a standard biography by an American professor: ‘Raven-haired with a moustache almost as full as Kitchener’s and lean as a rapier, he sounded like Ronald Coleman, dressed like Anthony Eden, and was adored by most women at first sight, and admired or envied by most men’ (Wolpert 1984:40). A British general’s wife met him at a viceregal dinner in Simla and wrote to her mother in England:

After dinner, I had Mr. Jinnah to talk to. He is a great personality. He talks the most beautiful English. He models his manners and clothes on Du Maurier, the actor, and his English on Burke’s speeches. He is a future Viceroy, if the present system of gradually Indianizing all the services continues. I have always wanted to meet him, and now I have had my wish.

(Raza 1982:34)

Mrs Sarojini Naidu, the nationalist poet, was infatuated: to her, Jinnah was the man of the future (see her ‘Mohammad Ali Jinnah—ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’, in J.Ahmed 1966). He symbolized everything attractive about modern India. Although her love remained unrequited she wrote him passionate poems; she also wrote about him in purple prose worthy of a Mills and Boon romance:

Tall and stately, but thin to the point of emaciation, languid and luxurious of habit, Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s attenuated form is a deceptive sheath of a spirit of exceptional vitality and endurance. Somewhat formal and fastidious, and a little aloof and imperious of manner, the calm hauteur of his accustomed reserve but masks, for those who know him, a naïve and eager humanity, an intuition quick and tender as a woman’s, a humour gay and winning as a child’s. Pre-eminently rational and practical, discreet and dispassionate in his estimate and acceptance of life, the obvious sanity and serenity of his worldly wisdom effectually disguise a shy and splendid idealism which is of the very essence of the man.

(Bolitho 1954:21–2)

However, Gandhi’s emergence in the 1920s—and the radically different style of politics he introduced which drew in the masses—marginalized Jinnah. The increasing emphasis on Hinduism and the concomitant growth in communal violence worried Jinnah. Throughout the decade he remained president of the Muslim League but the party was virtually non-existent. The Congress had little time for him now, and his unrelenting opposition to British imperialism did not win him favour with the authorities. As we shall see in later chapters, he was a hero in search of a cause.

In 1929, while Jinnah was vainly attempting to make sense of the uncertain political landscape, Ruttie died. Jinnah felt the loss grievously. He moved to London with his daughter Dina and his sister Fatima, and returned to his career as a successful lawyer. At this point, Jinnah’s story appeared to have concluded as far as the Indian side was concerned.

Securing a financial base

Jinnah had successfully resolved the dilemma of all those who wished to challenge British colonialism. He had secured himself financially. Sir Sayyed Ahmad Khan had to compromise; Jinnah did not. This difference was made possible by developments in the early part of the century: Indians could now enter professions which gave them financial and social security irrespective of their political opinions. Earlier, Indians had been seen as either friendly or hostile natives. The former were encouraged, the latter were victimized, often losing their lands and official positions.

Jinnah’s lifestyle resembled that of the upper-class English professional. Jinnah prided himself on his appearance. He was said never to wear the same silk tie twice and had about 200 hand-tailored suits in his wardrobe. His clothes made him one of the best-dressed men in the world, rivalled in India perhaps only by Motilal Nehru, the father of Jawaharlal. Jinnah’s daughter called him a ‘dandy’, ‘a very attractive man’. Expensive clothes, perhaps an essential accessory of a successful lawyer in British India, were Jinnah’s main indulgence. In spite of his extravagant taste in dress Jinnah remained careful with money throughout his life (he rebuked his ADC for over-tipping the servants at the Governor’s house in Lahore in 1947—G.H.Khan 1993:81). Dina recounts her father commenting on the two communities: ‘If Muslims got ten rupees they would buy a pretty scarf and eat a biriani whereas Hindus would save the money.’

In the early 1930s Jinnah lived in a large house in Hampstead, London, had an English chauffeur who drove his Bentley and an English staff to serve him. There were two cooks, Indian and Irish, and Jinnah’s favourite food was curry and rice, recalls Dina. He enjoyed playing billiards. Dina remembers her father taking her to the theatre, pantomimes and circuses.

In the last years of his life, as the Quaid-i-Azam, Jinnah increasingly adopted Muslim dress, rhetoric and thinking. Most significant from the Muslim point of view is the fact that the obvious affluence was self-created. Jinnah had not exploited peasants as the feudal lords had done, nor had he made money like corrupt politicians through underhand deals, nor had he been bribed by any government into selling his conscience. What he owned was made legally, out of his skills as a lawyer and a private investor. By the early 1930s he was reportedly earning 40,000 rupees a month at the Bar alone (Wolpert 1984:138)—at that time an enormous income. Jinnah was considered, even by his opponents like Gandhi, one of the top lawyers of the subcontinent and therefore one of the most highly paid. He also had a sharp eye for a good investment, successfully dabbling in property. His houses were palatial: in Hampstead in London, on Malabar Hill in Bombay and at 10 Aurangzeb Road in New De...