eBook - ePub

The New Doctor, Patient, Illness Model

Restoring the Authority of the GP Consultation

This is a test

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

"Peter's thoughtful model will hopefully enable future practitioners of medicine to argue against any retrograde move towards paternalism and authoritarianism."- Jonathan Silverman, author of Skills for Communicating with Patients, from the Foreword. This inspirational guide provides an innovative framework for understanding the consultation. It is concise, easy-to-read and highly accessible, presenting a simple and easily remembered non-linear diagram which facilitates the understanding of this richly complex process.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The New Doctor, Patient, Illness Model by Peter Bailey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Synoptic View of

the Consultation

INTRODUCTION

It is a precious jewel to be plain

Sometimes in shell the Orient’s pearls we find:-

Of others take a sheaf, of me a grain, of me a grain.

John Dowland, ‘Fine Knacks for Ladies’

Lute song from the Second Book of Airs1

Lute song from the Second Book of Airs1

Synoptic: Pertaining to or forming a synopsis; furnishing a general view of some subject

Oxford English Dictionary2

The consultation model presented in this book could be likened to the picture on the box of a difficult jigsaw puzzle. The consultation is endlessly complex and humans are very difficult to understand. Each of us lives our life in the centre of our own private universe of thought and feeling. Reaching out from that privacy and connecting with others is what gives our lives meaning. Our lives are enriched when we communicate and impoverished when we are unable to do so.

SCIENCE, ART AND TRUTH

In General Practice, all the information about the patient and the illness which the doctor is prepared to recognise has to be accepted as a communication with many meanings. On the other hand, the interpretation of this information, the process of testing hypotheses and solving problems, demands the intellectual discipline of the scientific method. Much therefore will be demanded of the future GP. He will need to acquire the approach to man which stems from science – both biological and behavioural – as well as the flair, imagination and compassion, the sense of tragedy and comedy, which characterize the arts.

Working Party of the Royal College of General Practitioners3

THE DOCTOR AS HEALER

It is curious that our power, and what we do as individual doctors to make people better – which is what many people value most in us – seem to get left out of our study of the consultation . . . At times of illness, crisis, loss or threat we all need attention, sympathy and support – indeed, a bit of loving approval. To be assured we have value and worth, that things may not be quite so awful as they feel, that there are features that are positive in what seems like an overwhelmingly negative situation, to have our intrinsic qualities objectively affirmed – these are universal human needs which fall to us as doctors to fulfil. Whether we like it or not, and find it embarrassing to talk about it ourselves, a primary task for us as doctors is to provide this: we are the healers, and society, and its individual members, need us.

Richard Westcott4

The hospital model was the foundation of my medical training, but I had already been inspired by the example of my own family’s general practitioner. I had seen at first hand the way in which he managed my mother’s anxiety when she called him to see my feverish sister. I knew that how you talk to patients is at least as important as what you say to them. I knew that there was much more to learn about communication than what I was seeing on consultant ward rounds. As a medical student I decided to look for a different approach and was fortunate to meet Dr Max Meyer, a GP who worked in Islington. His surgeries were filled with people who did not seem to have any disease or illness that I could recognise. They came to share their lives with him, the heartache of the human predicament of birth, love, loss, betrayal, courage and suffering – everything. He listened to them and thought about them. He would tell me stories about them after they had left and it was clear to me that they felt less alone having been met and understood a little. Of course, he would treat hypertension and diabetes and chest infections as well, but here was healing, in action.

CHAPTER 1

The Puzzle and the Picture:

Introducing the Synoptic View

The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.

William Shakespeare, As You Like It (act 5, scene 1)5

Since I qualified in 1979, I have participated in more than 200 000 consultations. I would like to offer a fresh perspective of what happens in a consultation – a general overview or ‘synoptic’ view. Consultation is not a linear process. It does not have a clear beginning, middle and end. Many of the elements are present even before the patient enters the room. The consultation is better thought of as recursive, or perhaps as a spiral, working towards meeting a patient’s needs.

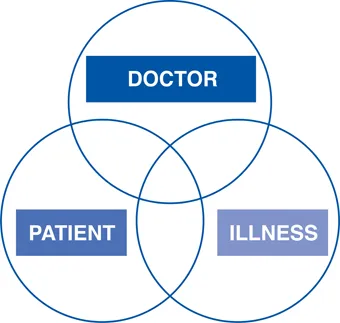

Here, then, is a new way of looking at the consultation. I have devised a simple and easily remembered diagram (as outlined in Figures 1, 2 and 3 in this chapter) that illuminates the richly complex process.

My starting point was the title of Michael Balint’s book The Doctor, His Patient and the Illness6 – a title taken from Hippocrates.7 This title outlines the three main protagonists in the consultation, although each plays a different role in the consulting room – each has an independent existence, separate from the other contributors. The narrative that emerges as the three interact is the stuff of the consultation. The deepest purpose of the consultation is meeting the patient’s needs, and I would argue that that is nearly always achieved by seeking to enhance the patient’s autonomy. With this as my guiding principle, I looked at the consultation from a storytelling perspective to see how the process can be facilitated and understood.

Box 1

The key to success lies in the creative activity of making new maps, not in the imitative following and refining of existing ones.

Ralph Stacey, Managing the Unknowable8

In the quotation shown in Box 1, Ralph Stacey9 makes it clear that the story of the consultation cannot be written in advance. That it why the Synoptic View of the consultation can help to orientate us in the dizzying turns and the blind alleys of the consultation. It is a guide to the nature of the unfolding narratives rather than any sort of prediction of what will be in them. Therefore, it is not prescriptive of tasks for the doctor, since these must necessarily emerge from the stories.

Drawing the protagonists as overlapping circles produces a diagram as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 The doctor, the patient and the illness

The overlaps between the three domains represent three quite distinct narratives. Each represents a story waiting to unfold. Each story needs time and attention spent on it if the goal of the consultation is to be achieved.

The three domains are:

- the patient’s story of the illness (which often focuses on subjective symptoms, thoughts and observations)

- the doctor’s story of the illness illness (which often focuses on diseases and organs, pathology and function)

- the doctor–patient relationship.

The central overlap where all three circles intersect represents the holy grail of consulting. Herein lies the right diagnosis, the best treatment, the patient with improved autonomy, shared understanding and all the other outcomes sought by GP gurus over the years. We are familiar with the idea of patient-centred medicine and doctor-centred medicine. What I am arguing for is consultation-centred medicine. A good consultation leads to outcomes that match need. These outcomes are authoritative because they respect the realities of the three protagonists. I am proposing a model that establishes the authority of the consultation.

The diagram now looks like that shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2 The stories within the consultation

The consultation does not occur in isolation, in a social vacuum. Both the doctor and the patient know their social roles. Their interactions are patterned and constrained by expectation, habit and fashion. Additionally, disease and illness themselves are not free of social meaning and significance.

There is a social boundary around the consultation and this can be represented by a triangle around the protagonists. Each aspect – illness, doctor and patient – has a unique social context, but all share in society. The conclusion reached in the shared understanding at the close of the consultation will reflect the mores and customs of that context. Now the diagram looks like that shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3 The Synoptic View of the consultation

This is the ‘picture on the jigsaw puzzle box’ that I have called the Synoptic View of the consultation.

Every consultation is a unique opportunity for meeting a person in his or her predicament, for making a difference. No map or diagram can encompass the complexity of the journey that results, but perhaps the model presented can steady the nerves and help to orientate the physician as the process unfolds. Just like the picture on the box of a fiendishly difficult jigsaw puzzle, this model can help you to see where the pieces fit. We find it almost impossible to perceive what we are not looking for, to observe what we do not expect to find. The consultation model can help you to perceive more in your consultations, to allocate what you notice correctly and to get closer to the right diagnosis and management. Using this model can enhance the authority of your consultations.

CHAPTER 2

The Doctor

FIGURE 4 The doctor

My thoughts about why I am a doctor have matured over the years, but my early experiences set my path and prompted me into general practice – the coalface of medicine. It is in general practice that unnamed illness and complexity seek to be understood. In 1972 a Royal College of General Practitioners document asked:

A woman of 30 presents to her GP with her three year old daughter. The child is irritable and badly behaved. She is crying constantly during the night and keeping the parents awake. Her elderly mother is due to visit, an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Part One: The Synoptic View of the Consultation

- Part Two: Consultations That Go Wrong: Using the Synoptic View as a Diagnostic Aid

- Part Three: Personal Reflections on Other Models of the Consultation

- References

- Index