![]()

1

The Human Body as the Foundation for Wearable Product Design

The human figure serves as the foundation for wearable product development. An understanding of human structure (anatomy), human function (physiology), and the actions of natural mechanical forces and energy in and on the body (biomechanics) can generate products that are compatible with complex bodies. Wearable product designers identify questions of “Who, What, Why, When, Where, and How” and apply product component knowledge to find a solution—a wearable product—that serves an individual’s needs.

Enrich and expand the design process by learning anatomical, physiological, and biomechanical terms. As terms (anatomical and product) are introduced in this book, they are italicized. Italicized terms, with definitions, are collected in the glossary. As you design a wearable product, use anatomical terms to reference (a) specific body structures, (b) sections of the body, (c) body processes, (d) relationships between body parts, and (e) body/product/environment interactions.

Anatomical knowledge can help you look at your user group or target market from a new perspective, see design problems in a new frame of reference, modify where and how you place your product on the body, and create innovative designs. Build anatomical, physiological, and biomechanical knowledge to set the stage for successful relationships between the human body and products and for advantageous interactions of the body and product with the environment.

Key points:

• The human body is the basis for wearable product design.

• The human body is wonderfully complex and variable.

• Anatomical terms can help visualize body structures and relationships.

• Anatomical terms provide a standard for team communication in the design process.

• Environments influence wearable product designs.

• The body can be characterized by its structure, function, and response to natural mechanical forces.

• Wearable products serve as buffers between the body and the environment.

• Wearable products must move with the body.

• Wearable product materials and structures influence body function.

• Variations in body structure complicate wearable product fit and sizing.

Words matter! Anatomists, professionals who study the human body, use an international language of terms defined by the structures of the body (Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology, 1998). FCAT terms, some including links to illustrations, are available online (http://terminologia-anatomica.org/en/Terms).

For purposes of this book, a wearable product is defined as anything that surrounds, is suspended from, or is attached to the human body. In some cases, wearable products are inserted into the body. Many products fit this definition—from fashion apparel to medical devices. While external medical devices like wearable blood pressure monitors and heart event monitors may be placed by a professional, they are included because they are worn for significant periods—a day or longer. Products like hearing aids and birth control diaphragms are placed in the body by the wearer.

When designers incorporate knowledge of body shape, form, and size in their design thinking, they can improve everyday wearable products like apparel. Shape is the two-dimensional outline (silhouette) of the three-dimensional body (form), viewed from the front, back, or side. Each person’s body has characteristic curves, planes, and angles. Product size reflects an individual person’s body dimensions.

Designers often plan a wearable product by looking at the body in a static pose. However, understanding the body in motion, the dynamic body, is important too. Gemperle, Kasabach, Stivoric, Bauer, and Martin (1998) developed design guidelines for best placement of wearable forms on the static and dynamic three-dimensional body. As you work on a design, accommodate body movement.

The designer’s job becomes more challenging as wearer demographics change and product categories expand. Population age shifts call for modification of product sizes, shapes, and forms to meet wearers’ changing needs. Global markets demand careful study of cultural differences in body ideals and of real body forms that influence wearable product designs. Wearable products for hazardous environments and medical and healthcare settings require in-depth knowledge of the human body. Understanding anatomy, physiology, and biomechanics prepares designers to meet new design challenges.

1.1 Body/Wearable Product/Environment

Two givens, the body and the environment, influence wearable product designs. Where do you begin in order to deal with the complexity of the body in the environment?

• Gather knowledge of human body form, function, and movement.

• Evaluate the environment. What are the environmental conditions? Are any of them hazardous?

• Manipulate wearable product components—structure, materials, and fit—to meet the needs of the body and the demands of the environment.

• Relate the structure and placement of the wearable product to the body and environment.

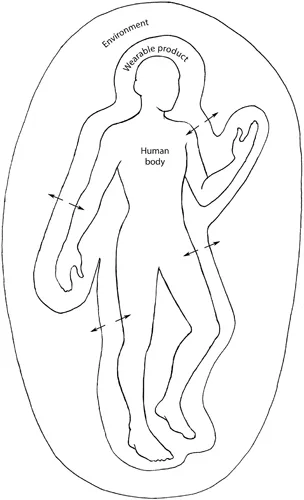

See Figure 1.1 for a simple illustration of the human body within the environment; the wearable product is the mediating variable. Understanding these factors is essential for the wearable product designer.

FIGURE 1.1

Human body/Wearable product/Environment interactions.

Anatomy is defined as “the study of structure” (McKinley & O’Loughlin, 2006, p. 2). The root of the word anatomy comes from Greek, meaning to “cut up” or “cut open,” harking back to the early pioneers in human body discovery as they dissected human remains to discover the mysteries of the body. Anatomists, medical students, and scientists use dissection today to study the parts of the body and the relationships of the parts. Understanding body structure is crucial when planning and implementing how a wearable product will be placed, attached, and work with the body.

Body structures suggest function; however, a separate scientific field, physiology, focuses on body functions and activities. Although this book does not provide in-depth explanations of physiological functions, basic body functions that affect design choices are covered as body systems in Chapter 2. Wearable products can hinder, enhance, or protect physiological functions. Laing and Sleivert (2002) delve into the effects of clothing and textiles on human performance (including physiology) in a comprehensive, thoughtful, and extensively referenced critical review. They specifically look at wearable product ergonomic requirements, design, fit, and material issues.

Over-heating in a hot and humid atmosphere illustrates how complicated body/product/environment interactions can be. Clothing might inhibit the body’s evaporative cooling by limiting air flow that could evaporate perspiration from the body surface. Clothing may reflect or shield the body from the sun’s heat. And wicking fibers may help cool the body by moving moisture away from the skin. The process of body thermoregulation involves the circulatory system, respiratory system, and the skin, part of the integumentary system—all discussed in Chapter 2. For a more detailed discussion of wearable products and thermoregulation see Laing and Sleivert (2002).

Body structures move in the environment and in relationship to each other according to the laws of mechanics. Biomechanics helps explain (a) the forces acting on the body, (b) the body’s center of gravity and base of support, (c) muscle work and power, and in summary (d) movements of the body in the environment (Everett & Kell, 2010). The mechanical nature of the body is most evident in the skeletal system and the muscular system, the body systems providing a body’s frame and motion. The human body is not well-suited to carrying loads. Bipedal mobility (upright walking), alone, produces significant stresses to the skeleton. Designing a backpack to suspend weight on a moving body requires applying biomechanical principles. Chapter 4 discusses some of the challenges of backpack design.

1.1.1 Environment

Designers consider where, when, and how their products will be used. A major focus of this book is the body’s relationship to physical environments. However, the social/psychological environment—expectations for personal appearance in a social/cultural setting—affects product acceptance. Physical environments can be non-threatening everyday surroundings, the situations most of us encounter every day. Environments can also be challenging; temperature extremes require wearable products that protect body functions. Extremely hazardous environments, like sites that have been contaminated with hazardous chemicals or nuclear waste, or areas where infectious disease is out of control, call for full body protection. Whatever the environment, understanding the human body is essential when designing wearable products.

Everyday Environments

Clothing that most people wear every day is designed to meet mass market needs and often falls into the fashion apparel category. In these settings, physical environments are not extreme, but understanding the social environment is important. All types of apparel, as well as accessories like hats, gloves, and shoes, are used in everyday-wear environments. See Chapter 3 for specifics on designing for the head and neck, Chapter 7 for information on hands and wrists, and Chapter 8 for details on feet and ankles.

The fashion industry uses an ideal image of the human body based on selected body measurements, a standardized company manikin, or a live fit model believed to represent the target market. Wearable products based on the standards can lead to consumer dissatisfaction, especially for those who do not fit the ideal. Mass market demands are blamed for these problems. Companies want to sell as much product as possible with the least cost, so product shapes are simplified and numbers of sizes are reduced. With an emphasis on simplification for economy, manufacturers do not incorporate information about forms, functions, and sizes of real bodies.

Sports and Athletic Environments

Designing apparel and equipment for sports and athletic activities requires comprehensive knowledge of body structure, function, and movement in the sport-specific environment. The requirements of the sport or athletic activity, characteristics of the playing environment, and interactions with other athletes who are part of the environment need to be addressed. Consider the similarities and differences in wearable requirements of swimmers and downhill skiers. Each activity is typically performed in a specialized setting and the athletes, amateur and professional, perform specific and often difficult physical feats. Profession...