![]()

1

Prelude

![]()

World Music, World Food

Sean Williams

If music be the food of love, play on.

Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

This cookbook comes to you from over forty contributors from around the world, almost all of whom are academics in music (ethnomusicologists in particular) or attached in one way or another to music and musicians. We have created this book as a way of celebrating the delicious and enduring connection between music and food.

I had been living in West Java, Indonesia, for about two months when Gugum Gumbira, the patriarch of my host family, paused between bites of fried rice one morning. “Soni!” he burst out. “You can already eat rice!” I tried to keep the shadow of a frown from my forehead, having heard this expression so many times and always with a tone of utter amazement. I had learned to use chopsticks at about the same time I learned to use a knife and fork as a toddler, so rice had always been an important part of my West Coast American upbringing. But Mr. Gumbira wasn’t finished. “If you keep eating this rice,” he said, “you’ll become completely Sundanese. It doesn’t matter how long you spend studying our music. You could be here for a lifetime if you want, and become the finest kacapi player in the country. You could be fluent in speaking Sundanese. You could dance jaipongan like a deer. But if you can’t eat the food we eat—and love every bite of it—you will never understand what it means to be Sundanese.” At the time I was still learning to tolerate the brilliant red spicy sambal sauce on my fried rice every morning, and to simply scoop out the dead ants that had discovered the sweetened condensed milk and coffee grounds in the bottom of my cup only to meet their doom in the form of boiling water. When he made that statement, I confess to having had a momentary longing for cornflakes, strawberries, and fresh milk in the bright sunshine (emotional and physical) of my parents’ kitchen. But he had a point.

In Indonesia (and in some other parts of the world), rice is food. Rice is what ascribes humanity to its consumers: when you eat rice, you become human. In other areas of the world, it might be kasha, or quinoa, or oats, or corn that makes you belong, locally. I recall my Sundanese friends being astonished to learn that Americans do not have a particular staple defining who we are, and that we do not expect foreigners to “learn” to eat what we eat in order to absorb American-ness. Yet people everywhere (including in North America) seem proud and delighted when an outsider grasps what it means to thoroughly enjoy local food. The need of a group of people to “claim” music (“This is what tells us—and you—who we are”) is at least as strong as their need to “claim” food-ways (“This is what tells us—and you —who we are”).

Ethnomusicologists (those of us who study music in cultural context) will tell you that we enjoy listening to music, playing music, thinking about music, and talking about music. Our connection to food, however, might be less obvious. On no fewer than five separate occasions in the past ten years, I have overheard ethnomusicologists jokingly say that they selected a particular area of the world to do research based on the compatibility and overall deliciousness of the local food. Many models of fieldwork hold sway in ethnomusicology, from our roots among the people running colonial empires to more contemporary efforts involving the Internet and electronic media. For years, however, ethnomusicologists have attempted to get close to music and the musicians who play it by living in situ, working frequently with one or several individuals or groups, learning the language(s) of the area, and practicing the classic fieldwork methodology of participant observation. While conducting fieldwork, some of us can easily purchase food imported (expensively) from our home nations, but many of us choose not to; local food is often all that is available, and local food is often absolutely delicious. Many of us, therefore, spend at least part of our lives in the role of musician-researcher-student of cooking.

The links between music and food are quite strong in many areas of the world; for some people, both are a vaguely threatening or sinful form of “entertainment.” For others, food and music must be “consumed” together for fulfillment. The parallels between learning to cook and learning music are often startlingly obvious: one person might be told to “watch what I do [on this instrument/with this whisk] and then try this on your own,” while a researcher in another part of the world might be told “put your hands right here [on this instrument/on this whisk] and I’ll help you make them do the right things.” Similarly, in one place it is appropriate to have absolute silence and solemnity during a meal and during a concert. In another place, uproarious laughter and ribald jokes are essentially healthy for both eating and listening. It is the rare ethnography that explores foodways in addition to music; this volume, therefore, represents a small step in the direction of what might be called gastromusicology.

The search for authenticity—in the field of ethnomusicology and in related fields of folklore and anthropology—has led directly to contested territory. Who gets to proclaim one musical style or language or political system or foodway as any more authentic than any other? Many ethnomusicologists (including several of this volume’s contributors) were born and raised in the “host country” from which these recipes originate. Others were not (myself included). For those born and raised in the country from which the recipes originate, these recipes might well represent some kind of national dish or must-have meal, or be a reflection of the creativity of members of that individual’s family. They might also represent a new creation as a result of being part of an immigrant or diasporic community. But we all have important ideas in common: a deep respect for the musicians with whom we work, a recognition that food and music are often conjoined in live context, and an understanding that we have much to learn from understanding food as a signifier of identity. As is the case with music, one could go blithely through this cookbook sampling bits of this and that cuisine, never extending below the surface. But I and the other contributors invite you to explore much more deeply: make a whole meal with all its constituent parts, listen to several CDs, ponder the included proverb, read the essay, talk to each other, and dig further for more information.

Perhaps the question should be whether we are all culinary and musical tourists in disguise, using food and music to explore, satisfy our curiosity, and redefine ourselves in our observations of the culinary and musical ways of others. I refer readers interested in this subject to Lucy Long’s excellent edited volume, Culinary Tourism (2004), which covers wide ranging issues in the arenas of tourism, foodways, and authenticity. In cautioning us against automatically championing the notion of authenticity, Arjun Appadurai claims that authenticity “measures the degree to which something is more or less what it ought to be” (Appadurai 1986, 25). He also points out that authenticity depends to a great degree on who is making the claim. It would be easy for any of the contributors to claim authenticity for themselves or their recipes, but you can rest assured that for every recipe or decision made about the contents of this book, a hundred others would rise to dispute it with great passion, all in the name of authenticity.

It might be useful to remember that you can’t have an “authentic” experience without a hefty dose of reality, often in the form of some negative experience involving, for example, extremely loud motorcycles, exhaust fumes from buses and trucks, startlingly large flying cockroaches, or hordes of ants. Sometimes “authenticity” includes food poisoning, more chili peppers than you might think humans could possibly eat, or items that the people of one’s home country do not necessarily think of as consumable. Americans rarely think twice about drinking water “purified” by chlorine, a known carcinogen, but some visitors to America are surprised and nauseated by its smell and taste, and can instantly detect its effect on the flavor of coffee and tea. Conversely, some Americans are somewhat challenged by the idea of eating entrails and profoundly challenged by the idea of eating bugs. I shouldn’t have to point out the physical similarities between the large exoskeletal creatures that Americans treat as delicacies (lobster, crab) and small, equally edible, ones (spider, locust).

I used to fret at my students’ fond attachment to Irish-American hit songs like “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” until I realized that it gave them firm emotional ground on which to stand, as Irish-Americans, while they began to explore the much more difficult musical territory of Irishlanguage sean-nós (old-style) songs. At the time I was dismissive of the entire Irish-American repertoire, failing to recognize its uniquely liminal authenticity for my students and its exploration of Irish-American experiences. For my students and for many Irish-Americans, that whole body of songs references for them an experience they need and understand; one that feels “just about right.” Of course you are, to some extent, attempting to stage an authentic event when you cook a meal and play CDs for your guests. Just be mindful that any attempt at authenticity is (and possibly should be, in this context) idealized.

Even as melodies or timbres of sound can take you back to your childhood, it is another sense—smell—that can have an even deeper effect. Knowing the impact of sounds and scents (and, by extension, tastes) on our deepest feelings can help us to recognize our vulnerabilities in determining what foods and sounds to trust. The sense of trust, of “just about right,” is part of what allows us to be adventurous. So although you won’t be instantly transported to Thailand, Tonga, or Tokyo by these meals and essays and CDs, they can at least start you on a fascinating and enjoyable path toward further exploration.

A good recipe is closer to a musical notation than to a blueprint. As a musician, I learned that the notes on the page represent what the composer intended but cannot possibly convey all of the nuances. Ultimately, the performer should decide just how loud ff is, just how short a staccato sequence should sound, or just how bouncy those triplets should be. One can recognize every performance as Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, but each will reveal a different interpretation. In the same way, ten cooks can make a classic Burgundian Coq au Vin from the same recipe. Each recipe will taste like Coq au Vin, but likely no two will taste the same.

Harvey Steinman, quoted in The Recipe Writer’s Handbook, 1997, 179

The intent of this volume is to offer sets of recipes from specific areas of the world. Each set of recipes makes enough food to feed six people, sometimes more. The recipes for these meals are intended to help you to create an entire meal, whatever the local definition of that meal is. In some areas of the world, one makes the main meal at noon and the family simply enjoys leftovers all the rest of the day and evening. For others, the food must be eaten at night. Sometimes men and women eat separately, or the children are fed elsewhere. Some people eat first while others wait their turns. Some people use only their right hand for eating, while others use chopsticks, a fork, a folded piece of bread, or an elaborate set of rules governing which fork or spoon serves a particular purpose. Each detail reveals much about the people in a community, just as the details of musical concepts/behaviors/sounds illuminate values, histories, and relationships.

Not one of the recipes in this book is exotic; each one is local, familiar, and just right to somebody. Exoticism is a matter of what we ourselves bring to the table or to the musical experience. After all, you (I’m talking to you: the one holding this book) are impossibly exotic to someone. Your manner of dress, idiomatic speech, choice of snack food, bathing habits, and tunes that you hum in the shower are funny, strange, frightening, and possibly even dangerous. The recipes for this book are different, in some cases, from what you might see in a standard cookbook from your region of the world, but they’re also just about irresistible. The contributors deliberately wanted to strike a balance between what is interesting and fun to try on the one hand, and too difficult to find or simply too far outside the “gotta try this” sensibility for large portions of the world. So we left out the grubs, dogs and horses, whole roasted kangaroos, fish head soup, and water buffalo lung chips that are nonetheless prized delicacies in parts of the world. Remember what I said about “exotic” foods; these, too, are just right.

Representation of world cultures is not uniform in this book. Instead, contributions have been welcomed from everywhere. For each set of recipes you will see a basic estimate of the amount of time it would take to complete the preparation of an entire meal. You will also find a translation of a pithy food-related proverb for each area represented, suggested recordings to listen to during the meal, and a list of resources for further exploration.1 In addition, each contributor offers an essay discussing food and music locally, with the individual emphasis that each area required. In requesting these essays, I deliberately asked the contributors to use their normal “voices” in a reflection of the ways in which we actually speak to each other and to other musicians. Many ethnomusicologists enjoy hanging out with musicians, spending late nights hearing “just one more song” or enjoying yet another encore. We rarely try to impress musicians with the brilliance of our postmodern academic discourse (although it can happen). Instead, we listen and talk naturally about food and politics and spirituality and sex and history…and music. We often eat while we talk, and many of us eat while we listen to music. Some people eat while they play music. It is the inherently interdisciplinary nature of ethnomusicologists and what we do that enables us to get excited about the many cultural products that extend beyond music.

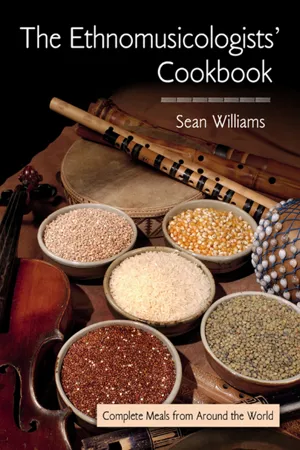

The cover photograph of this book combines the rich flavors and textures of essential foods from around the world: rice, corn, quinoa, kasha, and lentils, together with a variety of essential musical instruments from every continent. Like the grains, some of the instruments are specific to one region, while others (like the fiddle) have found a home nearly everywhere.

My thanks go to Martin Kane of the Evergreen State College for his outstanding artistry in arranging and capturing my rough idea with his camera. Piper Heisig gave me the unforgettable tagline for the back cover of this book, and our mutual friend Joe Vinikow offered other options from the world of Indian food: “My Pappadum Told Me,” “Oh, You Beautiful Dal,” and “Paperback Raita.” I would like to express my gratitude to Margaret Sarkissian for (literally) dreaming up the idea for this volume, to the Board of Directors of the Society for Ethnomusicology for agreeing to the project, and to the many contributors from around the world. Rebecca Ungpiyakul was my office assistant, and deserves my gratitude for keeping track of the many different contributions and permissions forms through the development of a handy spreadsheet. My husband Cary Black and daughter Morgan gamely sat through multiple meals—both successes and failures—as I tested them out. In addition, Richard Carlin, former music acquisitions editor of Routledge, was instrumental, so to speak, in supporting this book’s development. I would also like to thank Khrysti Nazzaro for deftly shepherding the project through to completion. The many ethnomusicologists (and their families and friends) who volunteered to test out these recipes had much to do with the overall ease of use and readability of the recipes. All these people—contributors, testers, editors, and people who like to eat—know that in many parts of the world, food and music are closely entwined. It is one of our many joys as working ethnomusicologists to bring the richness of our fieldwork experiences—including the wonderful food we eat—to our current lives and to the lives of others. Thank you for giving us the opportunity to bring some of that richness to you.

![]()

How to Use this Book

All these meals are designed to serve six people. While it would be delightful to always have six people at the table, few of us regularly invite five of our closest friends over for a meal. According to my tests, however, every one of these meals works extremely well as leftovers the next day. I have created a website [http://academic.evergreen.edu/w/williams/cookbook.htm] for more information about the meals, including photographs of many dishes, and a printable shopping list for each meal, which should enable you to avoid trekking back and forth through a store or from bakery to butchery and back by listing the ingredients in logical groupings (meat, dairy, produce, grains, miscellaneous). No one should have to be thinking, “What? I have to go back to produce for another onion?” Should you choose not to cook the entire meal, a quick scan of any individual recipe will tell you precisely which ingredients you need and in what quantities and what order.

Because this book is being published in the United States, all measurements conform to American standards. We understand that most of the world uses the metric system, and we hope that our metrically inclined readers wil...