Chapter 1: Between Materiality and Representation

Framing an Architectural Critique of Colonial South Asia

Peter Scriver and Vikramaditya Prakash

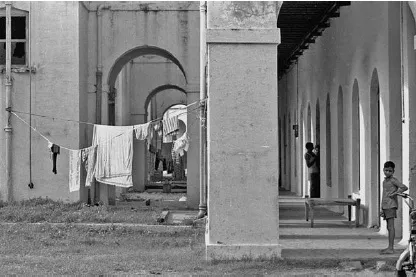

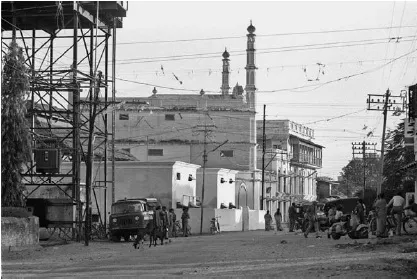

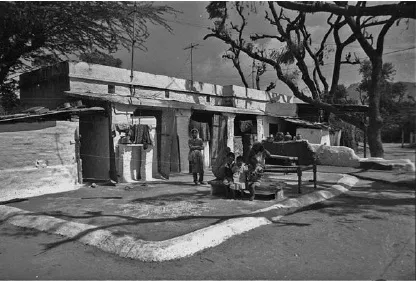

Along with the English language, and the colonial legal and administrative institutions in which it has remained enshrined, the buildings of British India and Ceylon are arguably among the most tangible and enduring legacies of the European colonization of South Asia. The material evidence of this is ubiquitous. At one end of the architectural spectrum there are the bungalows, barracks, institutional and technical infrastructure originally built to accommodate the everyday operations of the colonial administration and the droves of both “native” and “European” employees that served in its civilian and military branches. Countless examples of these humble structures are still in use today, particularly in smaller towns and settlements, where time and familiarity have woven them into the local fabric as if they had emerged from vernacular building traditions (Figures 1.1–1.5).

Figure 1.1

Bungalow, Civil Lines, Allahabad

Figure 1.2

Barracks, Fort George, Madras (Chennai).

Figure 1.3

General Hospital, Benares (Varanasi).

At the other end of the spectrum are the monumental architectural and urban legacies of imperialism, none so conspicuous as the capitol complex and ceremonial vistas designed by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker for Imperial New Delhi (Figure 1.6). Prized by politicians and preservationists alike, the spectacular stone structures of “Lutyens’ Delhi” continue to be the seat of government, and to represent the ideology of a paternalistic power embodied in centralized authority as intended by the former colonial regime.

In recent scholarship, the export to colonial India of the architectural forms and debates of “modern” Britain, and its ideological economy, have been relatively well studied. However, the actual building of this colonial architecture and its reception and inhabitation in the colonial-modern context have not received the equivalent attention required to fully appreciate the significance of this built legacy. Indeed, as the essays collected in the present volume explore, the building scene of colonial South Asia was not just a provincial theatre for the playing out of metropolitan ideas and fashions. It was a particularly distant stage on which representations of the modernity associated with the European imperial core – no matter how stilted a caricature – could assume a self-important authenticity merely by contrast to local practice. But imperial ideals of stability and purpose belied the progressively shifting social and political realities of colonial-modernity. In complex and often contradictory ways, the architectural and engineering hubris of modern Britain was engaged in and mediated by the peculiar theatrics of the colonial-modern situation. In the process, the cultural norms, aspirations and delusions of both the colonizers and the colonized were materially and symbolically embodied in the walls and spaces of their buildings. In turn these buildings framed their inhabitants in specific ways. In other words, the buildings – and, therefore, “the building” – of British India and Ceylon are not only critical parts of their respective colonial histories, but also particularly felicitous frames of inquiry through which those histories can be interpreted critically.

Figure 1.4

Police substation, Mhow, Madya Pradesh.

Figure 1.5

Peon quarters, Ajmer, Rajasthan.

Figure 1.6

Central Secretariat Blocks and Viceroy’s House (Rashtrapati Bhavan, today), from Central Vista, Kingsway (Rajpath), New Delhi.

Whilst interpreting the roles of building and dwelling in processes of cultural construction and re-production, the present essays also underscore the creative implications of architecture within colonial social histories. The walls and fences of the built environment were among the most concrete and explicit means by which colonial administrations attempted to divide and rule. But buildings also served to define and frame “in-between” spaces within the colonial social field – places of cultural contact and intersection where hybridity and innovation were enabled. Colonial architecture and building comprised a framework in which the values and identities of the new colonial-modern social classes that emerged under colonial rule found form.

THE IN-BETWEEN-NESS OF THE ARCHITECTURAL FRAME

A brief look at the way architecture is engaged in a tragicomic novel about cross-cultural hybridity in colonial-modern India will help illuminate the inventiveness inherent in the schizoid nature of “in-between” spaces. Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh begins in the early years of the twentieth century in what is described as a “grand old mansion in the traditional style … set in a rich man’s paradise of tropical foliage.”1 This is the estate of the da Gama clan, the wealthy South Indian Christian spice merchants who are the protagonists of the tale. With Rushdie’s fleeting description of the syncretistic building style of the steamy coconut-lined coast of tropical South India we are drawn into the world of colonial nostalgia and cross-cultural invention. Sequestered on a private island in the balmy harbor of colonial Cochin, the labyrinthine house and gardens are an Edenic microcosm of invented traditions and hybrid constructions, a lost world of colonial cultural miscegenation. One imagines Tagore’s Shantiniketan, or the Shahibaug estate of the Sarabhais of Ahmedabad. The Cinnamon Gardens mansions of colonial Colombo that Anoma Pieris explores in her contribution to the present volume offer another image, stylistically and climatically closer to Rushdie’s South Indian setting – a colonial-modern idiom derived and elaborated, as Pieris describes, from the same hybrid distillation of Portuguese, Dutch and indigenous vernacular building forms that would later inspire the romantic regionalist designs of architects in post-independence Sri Lanka.

Early in the story the rhetorical function of the old da Gama house and its grounds is brilliantly exploited in an incidental vignette in which Rushdie teases the architecturally informed reader with an apocryphal episode in the hagiography of modern architecture:

Francisco da Gama came home one day with an impossibly young and suspiciously winsome Frenchman, a certain M. Charles Jeanneret, who put on the airs of an architectural genius even though he was barely twenty years old. Before [Francisco’s wife] could blink, her gullible husband had commissioned the jackanapes to build not one but two new houses in her precious gardens. And what crazy structures they turned out to be! – The one a strange angular slabby affair in which the garden penetrated the interior space so thoroughly that it was often hard to say whether one was in or out of doors, and the furniture looked like something made for a hospital or a geometry class…; the other a wood and paper house of cards – “after the style Japanese,” he told [her] – a flimsy fire-trap whose walls were sliding parchment screens … Worse still [she] soon discovered that once these madhouses were ready her husband frequently tired of their beautiful home, would smack his hand on the breakfast table and announce they were “moving East” or “going West”; whereupon the whole household had no choice but to move lock, stock and barrel into one of the Frenchman’s follies…And after a few weeks, they moved again.2

This vignette provides a wonderfully wry example of how architecture might have “performed,” so to speak, in the process of colonial-modern cultural construction. Through contrasting architectures, Rushdie represents the binary opposition that is perceived to be inherent in the characters’ cross-cultural pedigree. The architectural follies are caricatures of “East” and “West” that represent entire cultural worlds. Through the narrative juxtaposition of these absurd but materially and symbolically tangible frames of reference, the reader is able to understand something of the cross-cultural predicament. Framed in this way it is, quite literally, an existential quandary. The characters remain schizophrenically unsettled in these alternative architectures, perennially shuttling from folly to folly, with periodic retreats back to the more accommodating and comfortable ambiguities of the hybrid main house to ponder their discontent.

Figure 1.7

Hybridity in the domestic space of the colonial-modern bourgeoisie. Furnished veranda, Colombo, ca. 1900.

Rushdie’s fictional “constructions” are an intriguing conjecture on the agency of architecture in the awakening of a colonized society into postcolonial consciousness. They underscore not only the obvious relevance of the designed environment within the wider ambit of social production, but also its particularity and its significance for the critical interpretation of social development and change in colonial contexts. Specifically, the pavilion vignette presents us with playfully exaggerated distinctions between (1) essentialist, ethnographic framings (the “Eastern” folly), (2) formalistically skewed historicist framings (the “Western”/“Modernist” folly), and (3) the hybrid ambiguity of a colonial-modern synthesis (the old mansion). These alternative dwellings foreground and critically expose both the material and the representational registers through which architecture operates to frame cultural norms and practices. The binary oppositions between the two follies also characterize the problematic dichotomies that pervade much of the scholarship to date on the architectures of colonial and contemporary South Asia. But it is the hybrid dwelling – the one that is relatively ambiguous with respect to its materiality and symbolic function – that holds our attention and proves the most robust and realistic of the three. Primarily a spatial phenomenon, rich in both texture and meaning but irreducible to either, the old colonial mansion embodies a “space” of everyday life in which different worlds can intersect: a place of cultural and historical in-between-ness (Figure 1.7).3

For interpreters of the distinctive vernacular and contemporary building patterns of South Asia, the “in-between spaces” of architecture – what the pioneering documenter of the Rajasthani vernacular, Kulbhushan Jain, has called “realms of transition” – have had a particular and long-standing resonance, largely independent of the wider topicality of this notion in contemporary architectural discourse.4 The “in-between” has also been a focus of much recent inquiry across a variety of other disciplines concerned with colonial pasts and presents. Postcolonial cultural theorists have addressed the problematic but equally liberating ambiguities of identity arising from the hybridity and (dis)location of culture in the world today. Departing from Edward Said’s seminal critique of the constructed opposition of “East” and “West” in the Orientalist discourses of colonial literature and scholarship, this work has explored the critical relationships between the spatial and conceptual frameworks of this “globalized” contemporary world and the historical experience of colonial imperialism that substantially prefigured it.5 For their part, critical historians of colonialism have directed increasing attention to the tensions of empire that were vested in the in-between position of the subordinate rank and file of colonial administrations – “native” and “European” – and to the ambiguous intersections that blurred distinctions between colony and metropole.6 As the historians Ann Stoler and Frederic Cooper describe, there has been a shift in the predominant focus of their field, from a unilateral concern with the coercive determinism of metropolitan power and desires in the colonial situation to the examination of how both the colonial and the metropolitan spheres of empire participated in the dialectics of inclusion and exclusion.Within the in-between space of this imperial exchange, postcolonial historians examine how hierarchies of production, power and knowledge emerged in tension with the colonial extension of modern European notions such as universal reason, liberty, market economics, and citizenship.7

Not unexpectedly, some of the most compelling critical scholarship on colonial space and society has been characterized by its interdisciplinary approaches. Building on sociologist Anthony King’s seminal early studies of colonial urban development and the material culture of domestic space in British India, such work has explored fruitful overlaps between architecture and other fields such as cartography, geography, sociology, anthropology and cultural theory to examine how power is exercised in and through space, not least through the construction of hybrid spaces.8 This is an ongoing enterprise. As the historical geographer, Richard Harris, articulates, this spatialization of hybridity in colonial contexts continues to raise compelling questions for further cross-disciplinary inquiry. Did colonial power intentionally resist hybridity, as certain colonial discourses would suggest, representing it only as it suited the political purposes of the regime? Or was the hybridity that pervaded colonial building forms and practices the evidence of an inevitable compromise, an expression of the limitations of colonial rule and resistance to it? If such resistance and negotiation was indeed demonstrable, to what extent was this experience a generalizable phenomenon across different colonial situations?9

In the small and often self-consciously autonomous architectural literature regarding the colonial empires, however, such interdisciplinary queries and insights have made relatively few inroads to date.10 Although the architectural legacies of British India have received comparatively more scholarly attention than most, there remains unfortunately a marked disjunction between empirically grounded formalist accounts of this material and largely theoretically grounded critical inquiry in this field.

The formal characteristics of the monumental and, to a lesser extent, the mundane architecture of colonial India have now been relatively well documented in a growing body of literature, both scholarly and popular, published since the 1960s.11 Nevertheless, there is still much work that needs to be done to explain adequately the relationships between the cultural construction of colonial South Asia and the actual formal construction, operation and performance of the built environment. The topic has had only limited benefit from the theoretically engaged interpretations that we have seen, for instance, in the parallel literature on the architecture and urbanism of French colonial Africa and Indochina.12 The architectural discourse on colonial South Asia presents a conspicuous pattern of silences and obsession with questions of stylistic hybridity and related issues arising from the perceived conflict in the architecture of colonial-modern India between the traditional building crafts of the subcontinent and modern European design principles and methods. As the present authors explore in our respective individual essays, that pattern of intention reveals as much about the discursive contexts and premises of those debates as it does about the historical artifacts and issues in question.

The essays in the present volume examine the manner in which the buildings that arose from and framed the fraught and ambiguous experience of colonial modernity might be regarded as “still frames” – to employ a useful cinematic metaphor – of a continuous, dialogical process of cultural construction and change.13 They explore some of the ways in which architecture, from humble dwellings to monumental public buildings, constitutes distinct and particularly revealing frames of practice within the matrix of interconnected colonial discourses. However, we believe that such architectural inquiry has a potential wider relevance and usefulness for interdisciplinary cultural and colonial studies as well. As our subtitle suggests, our broader aim is to discern critically productive strategies, not only for further fruitful study of colonial architecture in the Indian subcontinent, but also for thinking critically through that architecture about colonial modernity more generally.

THINKING THROUGH ARCHITECTURE AS FRAMES OF PRACTICE

Previous scholarship on architecture in colonial India and Ceylon reveals a distinct polarization of concerns. On the one hand, discipline-conscious architectural writers have tended to focus on the material form and style of individual buildings; what we could characterize, by analogy with language, as the vocabulary and grammar of this architecture. On the other hand, extra-disciplinary observers have primarily been interested in semantics – that is, in interpreting colonial architectures and the built environments they comprised as a form of meaningful text in which the cultural politics of colonial-modernity were represented.

Descriptive in nature and synoptic in scope, the large majority of this existing literature has ...