eBook - ePub

Your Move: A New Approach to the Study of Movement and Dance

A Teachers Guide

This is a test

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The author takes a new approach to teaching notation through movement exercises, thus enlarging the scope of the book to teachers of movement and choreography as well as the traditional dance notation students.

Updated and enlarged to reflect the most recent scholarship and through a series of exercises, this book guides students through:

movement, stillness, timing, shaping, accents

travelling

direction, flexion and extension

rotations, revolutions and turns

supporting

balance

relationships.

All of these movements are related to notation, so the student learns how to notate and describe the movements as they are performed.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Your Move: A New Approach to the Study of Movement and Dance by Ann Hutchinson Guest in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Specific Notes for Each Chapter

CHAPTER ONE —MOVEMENT; STILLNESS; TIMING

Simplicity can often be more difficult than complexity. The very simplicity of being asked to perform one action followed by stillness may cause a mental blank. What should that first action be? Indecision sets in. That first action can be ANYTHING! Turn, double over, lower to the floor, wave the arms, reach for the ceiling, twist to one side, or just take a deep breath and allow whatever other movement may begin to emerge to do so. A swaying of the torso can also initiate movement which can then develop further. Here is the first example of concentrating on the possible freedoms in interpreting the instructions; there need be no constraints.

Such a very simple start usually means that the mind makes a decision, selects an action and that action is done. Perhaps the student is feeling facetious and just waggles a little finger. Good enough! If any action is asked for, that is an action, and so it qualifies. Any mentally directed action is a start. However, with the mind in control, the movement often is physically empty and meaningless. Even ‘an action’ can have meaning, content, intention, motivation, a reason for having occurred. If the mind can set the spark for such actions, that is fine. It is important that each action reaches the inner fibres so that it becomes totally a physical movement.

An Inner, Physical Source

Encourage students to find a movement from within. Remind them of how Isadora Duncan would stand motionless for great lengths of time, waiting for a movement to happen, waiting for it to be given birth from within. For many students such a way of originating movement may seem embarrassing, but with eyes closed and breathing allowed to assist in the ‘birth’ of the movement, they will not find it so hard. The movement may grow out of breathing. Martha Graham also used the same source, with very different results. Her movement was totally physical and for that reason it ‘spoke’, as did Duncan's. The kind of movement, the style, is not important; it must be a true movement, real, and not just a mentally manufactured action. Not that thought-guided movements cannot be very effective and not that they do not have their place, but there is a time to think and there is a time to transfer thoughts of movement, movement ideas, into physical actualities. It is this actuality, the total body action, that we are concerned with—an experience which students enjoy fully. It is for this reason they must be encouraged to lose their self-consciousness and be able to immerse themselves completely in the ‘moment of truth’ as Martha Graham so eloquently described it, the reality of movement experienced to the full.

Stillness

If one is to analyze it, the achievement of stillness is a matter of dynamics. The expression, the ‘taste’ or ‘flavor’ of the previous movement must ‘sing on’ during the cessation of movement change. This quality is produced by a particular outward free flow within the body. At this stage we do not want to go into analysis of dynamics but to give an image which will produce the desired result. The gap on paper between movement indications means ‘no change’, but the gap does not give information on how that period of ‘no change’ is to be handled. To develop greater body awareness we want that pause to be ‘alive’, not ‘dead’, hence the importance given to the idea of stillness in movement. It is not a retention, a holding, a ‘keeping’ statically; therefore a special sign exists.

Suggested Movement Examples

Slow Actions

For the very slow action on page 5 the following ideas are suggested:

a) A slow extending of the arm forward high, with the rest of the body, particularly head and shoulder, taking part, i.e. contributing to the action.

b) A sustained horizontal arm gesture starting across the body and moving on a circular path to the open side. An upper body twist and lean from one side to the other augments the movement; the weight may also shift slightly to add to the overall effect.

c) From a closed position sitting, a gradual extension, reaching out from the center. This movement could also be achieved in a lying position.

d) From an extended starting position the whole body may close in, contract or fold up. A slight twist and asymmetrical use of the arms and legs add interest.

Encourage the students to use general, overall body movements in which the parts move in harmony with one another, each supporting the main movement idea. It is not wrong to do a very slow flexion or extension of the hand, for instance: isolated actions can express the basic idea of sustained motion; but if a stated action is made the focal point of an overall body movement, the expression is richer and the movement is experienced physically to a greater degree. Movements which are too isolated—crooking a finger, flexing the wrist—too easily become actions which the performers are producing only cerebrally: the movement is peripheral to them, they are ‘outside it’ so to speak and not personally involved. Such isolation is better explored later; in the early stages the performer should sense the body as a whole so that all parts work in concert even if some contribute only slightly. The idea of such supporting movements can be compared to that of a group of actors on stage in a situation where the key figure is talking and the others are reacting, taking part by focussing on the leading actor.

Swift Actions

For the three swift actions on page 6 there are also many possibilities. Speed tends to mean that use will be made of the extremities rather than of the center of the body or the head as a whole. Hands and head can move quickly and quick steps are easy; short sharp gestures of arms or of a leg or perhaps a shoulder movement can serve. There is a natural tendency toward smaller use of space, though this need not be so: swift jabbing motions can cover much space. The students should experience actions of the same speed but using greater or lesser space. If three steps are chosen for the three swift actions, care must be taken that they do not in fact produce one continuous pattern of travelling, which will happen if all three steps are into the same direction. Changes in step direction express separate actions. Many students choose to jump to express swift actions. Any form of springing is usually not satisfactory for this purpose because a spring requires a preparation and a landing; it is not a one-part action and is less easily controlled. For leg activity a flick of the lower leg, a swift knee lift, a sudden bending of the free leg or a quick rotation in or out while it is bent can be expressive and enjoyable to do.

Separated Actions

Every student finds it difficult to leave enough time between actions for the stillness (the separation). Physical awareness of time going by while one is being still needs to be developed. Experience shows that if a gap appears on the paper the performer wants to rush ahead to the next movement indication. A discipline in time is needed to control this rush which is not unlike the tendency for people clapping to start getting faster and faster. Although no deep exploration into the physical experience of time is included in this book, whenever possible students should be made aware of how they are using time and learn to be correct in time without loss of performance spirit and quality.

Reading Study No. 1: Movement Patterns in Time

This study can be performed while sitting, kneeling or standing. It lends itself to flowing arm gestures, hence the suitability of sitting or kneeling. However, if the performer is standing, some of the sustained actions could be interpreted as sustained transferences of weight. The whole study could concentrate on steps, slower and faster, or it could be a ‘dance’ just of the hands, with the body swaying or reacting in some way to augment the hand patterns. A single arm might perform the first phrase of four measures, or the arms may alternate for each new action. After a first general exploration you may wish to provide the further discipline of one or other of the abo ve ideas in order to produce more inventiveness. If different groups are given different disciplines (use of hands only, steps only, one arm only, alternating arms, etc.), the class would have the advantage of comparing results, ascertaining which disciplines produced good movement patterns, which did not work as well, and discussing the reasons for the differences.

CHAPTER TWO —TRAVELLING

Travelling has been chosen as the next basic movement to explore because it is such a familiar everyday activity. And yet, despite its prevalent use in dance, its full potential as an expressive movement is seldom realized. The body is ‘handled’ differently, that is, it prepares itself differently according to 1) whether a straight or curving path is to be performed and/or 2) whether a goal is to be reached or travelling is embarked upon for its own sake, i.e. the pure enjoyment of going. The general sign for ‘any path’ can be interpreted as selecting and performing one specific path, or it can be a selection from the five possibilities, the performer intentionally changing from one form to another within the stated duration of the path.

Straight Paths

Straight paths need little introduction; they are familiar and comfortable, and students (as well as small children) enjoy travelling on them, particularly at speed. Running is a pleasurable way of traversing the room. Every straight path must come to an end in a room; thus a turn must take place in order for the performer to face another direction and be able to go off again. How much of a turn occurs depends on which new direction is chosen. This turn is not important; it happens swiftly and without emphasis. Encourage pauses between paths, both in changing direction and also in continuing into the same direction. Once forward travelling has been covered the next step is to travel sideward and backward. Walking or running backward should be experienced until any fear is removed. Looking over a shoulder will enable one to see where one is going. Reaching backward with an arm also helps guard against bumping into someone or a wall. Once different step directions are familiar and comfortable, patterns should be made changing from forward to backward, to side, etc., and combined with changes in length of path and different destinations in the room.

Reading Study No. 2: Straight Paths

This study provides a simple symmetrical pattern in which to explore step directions. The simple cross is the basic design of many Asian dance patterns, a choreographic form also found in European folk dance.

Meandering, Curving, Circling

The differences between meandering, curving and circling are not always readily understood. Meandering is of the moment, it is unplanned. One enjoys the ‘going’ with no thought of the exact shape the path will make. In curving the performer consciously indulges freely in space. A sense of flow and a free carriage of the body can give rise to curving paths, as when an elegant hostess sweeps through the room to greet her guests. Similarly, obstacles may be avoided by curving around them, sweeping one's garments out of the way. The degree of curve is not important, it should come from the feeling, the expression. While in the course of meandering, straight paths may occur, in curving they do not.

In contrast to curving, circling involves definite shapes. A circle has a center, and the performer should be aware of this focal point. It is around this point that the circular path moves. There is no cutting corners, no ‘cheating’ in performing true circles. It is the fullness of the circular outline which gives enjoyment to performer and observer.

Concept of Circular Path

Walking circles would seem to be child's play, an activity for which no training, no real thought is necessary. Alas, this is not so. First the right concept has to be established. Most students have the idea that in walking a circle they start from the center of the circle and work their way out. This image needs to be corrected early on. In Your Move text an image of a wheel is given. Another image, possibly more helpful, is that of winding a string around a drum. As the string is wound around, Ex. 301a, it is taking on the shape of the drum. The performer is at the point where the string meets the drum. In 301a and b) a tiny figure has been drawn at this point. Because of the usual difficulty in getting the right image Merlin's Magic Circle is introduced in the book.

Teaching Aid for Circling

As principal of the Philadelphia Dance Academy Nadia Chilkovsky Nahumck had a large circle painted on the floor of the foyer so that children waiting for class could experiment with the many ways in which they could travel on that circle. Thus what to them was a game was in fact a valuable teaching aid and those moments of waiting were put to good use.

Once the concept of one's relationship to the center of the circle is understood, it should be possible to walk perfect circles with any number of steps. If eight steps are taken it is easy to apportion the number of steps needed for each quarter circle and so produce an even gradual change of front. But even with a divisible number such as eight or twelve, most students will describe ‘balloons’ of various shapes by turning too little, too much, or by making uneven spatial adjustments. Some turn too sharply and then end up with several steps straight forward. Many do not realize at first that a perfect circle should end where it started. Outside aids such as chalking a circle of the appropriate circumference on the floor help to establish the visual image, but more important is to get

an inner feel for the circle, an awareness of the shape the body is describing. Once such awareness is developed, circles with five steps, seven steps, thirteen steps, etc, should be tried.

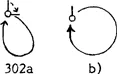

The most common mistake made in walking a circle is to begin by making a quarter turn into the direction of the circling before starting to walk, Ex. 302a. If the students have grasped the idea that they should end where they started, the floor design will look something like 302a instead of 302b.

Creative Exploration: A.

Once the basic path shapes have been explored and the signs for each introduced, the following is a good approach to further clarification before the Reading Study or Exercise Sheets are done.

Have each student draw a floor plan using straight, meandering, curving and circular paths. You may wish to set the sequence so that all have the same basic material to work from, as for example in 303: ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- GENERAL NOTES

- Use of YOUR MOVE

- SPECIFIC NOTES FOR EACH CHAPTER

- THE EXERCISE SHEETS : ANSWERS