This is a test

- 314 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Slonimsky's Book of Musical Anecdotes

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Scathing reviews, whimsical stories, and diverting games fill the pages of this utterly engaging kaleidoscope of skewed tales on the world of Classical music. It dishes out a marvelous feast of tales served up by a master storyteller whose reach extends around the world and to the beginnings of civilization.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Slonimsky's Book of Musical Anecdotes by Nicholas Slonimsky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Música. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II

NOT TO BE FOUND IN AUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHIES

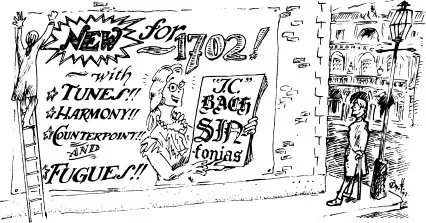

Periodical Symphonies

What is a Periodical Symphony?

The first Bach’s son, Johann Christian – called the “English” Bach because he lived and died in London – has a set of six “Periodical Symphonies” among his works. The title sounds intriguing, conjuring up notions of a symphony with periodically recurring themes. But actually they are nothing of the sort. The title was merely the publisher’s way of indicating in his advertisements that he was in the business of publishing symphonies periodically.

For Decayed Musicians

Benefit concerts in eighteenth-century London were outspoken affairs in which the circumstances and need of the beneficiaries were described in the advertisements.

Johann Christian Bach took part in several such benefit concerts. One was given “for the relief of Lady Dorothy Dubois, eldest lawful daughter of Richard, the last Earl of Anglesey,” who, as a child of her father’s secret and bigamous marriage, was deprived of her inheritance. Johann Christian Bach was said, in this advertisement, to be “as conspicuously endowed with soft compassion as unequaled in harmony and superiority of genius.”

The most intriguing of these benefits was for “decayed musicians”–though the advertisement failed to specify whether the “decayed musicians” were living or dead.

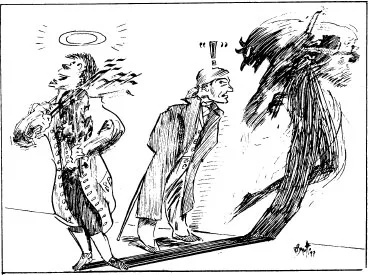

Corelli, the Archangel

Arcangelo Corelli, whose historical importance rests in his having made a virtuoso instrument of the violin by writing difficult solo pieces and performing them with brilliancy, was visited in Rome by the German musician Strunck.

“What instrument do you play?” Corelli asked.

“A little violin and a little harpsichord,” replied the other, “and I should be delighted to hear you play.”

Corelli acceded to the request and played some of his own music.

“Truly you are an archangel,” remarked Strunck, with allusion to Corelli’s first name. “But in your technique you are an archdevil.”

Trumps in D

Handel was displeased with the new music that he heard in his day in London (circa 1750). He particularly objected to the constant shifting from the tonic to the dominant in the trumpets. When he heard such music he used to laugh and exclaim – using the terms of his favorite card game: “Now D in trumps, now A.”

The Murder of Leclair

On October 23, 1764 early in the morning, a Parisian worker passing by the suburban cottage belonging to the sixty-nine-year-old French violinist and composer, Jean-Marie Leclair, noticed that the door was open. At the same time Leclair’s gardener was leisurely walking toward the house. They exchanged remarks and soon noticed that the Leclair’s hat and wig had been tossed on the ground in the garden. Alarmed, they awakened the neighbors and went into the house. There they found a frightful scene. Jean-Marie Leclair was lying on his back in the vestibule, his jacket and his shirt covered with blood. He had been stabbed three times, in the left shoulder, in the stomach, and in the chest. Next to the body were found several objects that seemed to have been put there intentionally, a book entitled L’Elite des bons mots, some manuscript paper, and a hunting knife, which, however, bore no traces of blood.

The police opened an inquest. The obvious suspect was the gardener, who had a prison record. His testimony was confused and contradictory; he declared that he had noticed the open door at six o’clock in the morning, but several neighbors testified that they were awakened by him to come for help at half-past four. The police questioned a woman, admittedly the gardener’s mistress. She said that on the night of the murder, the gardener arrived at her house at ten-thirty, while he had maintained he had been there from seven o’clock on. Another woman testified that the gardener had threatened he would take care of her husband in the same way that Leclair had been dispatched.

The motive could not have been robbery; four gold pieces were found in a drawer of Leclair’s desk where anyone familiar with the household would have looked. On the other hand, the watch that Leclair was known to possess was not found on the body. The gardener claimed that Leclair had lost it eighteen months before, but the proprietor of a billiard room which Leclair had visited on the night of the assassination testified that he had taken out his watch to look at the time at about a quarter of ten.

Another suspect was Leclair’s own nephew, himself a musician. It was known that he had pestered his uncle with demands to recommend him as a household musician to the Duke of Gramont. He was reported as having spoken of his uncle as a miser with no feelings for his family or friends, and as having said that Leclair would some day meet with a violent death. But all this talk was ex post facto, and nothing definite could be pinned on the nephew.

The police inspector in charge of the inquest wrote:

“The nephew merits attention; his extraordinary state of agitation and trembling at Leclair’s interment noted by my men, whom I had sent to the funeral, and also by others, adds to the circumstantial evidence against him, and makes him highly suspect. I also know that he enjoys the favor of Leclair’s widow, which justifies my interest in her part as well. At the same time, I do not abandon my suspicions against the gardener as some information seems to point against him.”

Leclair lived alone. He had been estranged from his wife for some years; yet his association with her was not interrupted, for Madame Leclair was not only his wife but his publisher as well. She was a remarkable woman who had learned the art of music engraving, was an expert with the tools of her trade, and seemed to be a person of uncommon energy and physical strength. She continued to print his music even after the separation. Madame Leclair testified that 841 lead plates of the compositions of her late husband were, at the time of his death, in the hands of the printer as a guarantee for the sum of 1,150 livres which the Leclairs owed to the printer. The printer also had in his possession twenty-five copper plates of the engraved map of Paris, also the work of Madame Leclair.

Even the Duke of Gramont was drawn into the inquest despite his rank and position. He made a written statement:

“I visited M. Leclair only twice, and I did not drink nor eat at his house; such company is not for me. For seven or eight years I have not drunk anything but water.”

The Leclair’s widow enjoyed considerable favor in court circles. She was able to help Leclair to obtain excellent commissions from royal patrons and from the king himself. Her interest in the affairs of Leclair’s nephew may have played a role in the ultimate estrangement of the couple. The vague suspicion voiced by the police inspector in regard to the role of Madame Leclair in the murder was not followed up, and the affair was declared closed without the uncovering of the culprit.

The police never made clear that the assassin must have been known to Leclair and received by him at his house at an appointed hour, probably between ten and eleven in the evening, after Leclair had looked at his watch in the billiard room. The three wounds were inflicted in the front part of Leclair’s body as he faced his murderer; they might have been caused by a sharp tool used for music engraving – yet there was no examination of these tools in Madame Leclair’s apartment in Paris. The correspondence between Leclair and his wife during the period of estrangement was not examined; their business arrangements during that period were not investigated. The meetings between Leclair’s widow and his nephew after his death were not watched. Obviously this line of inquiry was not favored by the authorities.

Yet the picture of the assassination should have been clear. Madame Leclair went to see her husband and urged him to help his nephew in obtaining a position with the Duke of Gramont. Leclair, being jealous of his status with his wealthy patrons, refused to do so. He probably accused his wife of showing undue interest in his nephew’s welfare. Madame Leclair must have brought with her a chisel or some other tool used in engraving, in anticipation of violent argument, perhaps for self-defense. Being a novice in assassination, she failed to reach Leclair’s heart and struck three blows in three parts of his body in order to accomplish fatal results. From all evidence it appears that she spent some time in the room after the murder arranging the objects around his body, removing his hat and wig and leaving them in the garden, all in very amateurish fashion, and at the risk of having been discovered. Only a person intimately acquainted with the victim’s mode of life could have gone through these motions. Only a person who knew Leclair’s interest in books and music would have placed a book ot quotations and music manuscript paper next to his body. Such a person could only have been Madame Leclair, the first woman publisher and music engraver in the annals of music history.

Hail, Farewell Symphony

The story of Haydn’s Farewell Symphony is a favorite among music commentators. The accepted version is that Haydn wrote this symphony as a gentle hint to his employer, Prince Esterházy, that his musicians deserved a vacation from their labors. The hint was found in the Finale when one player after another departs from the stage until only the first violinist is left.

This story has a strangely unconvincing ring about it. Why should Haydn have employed such a subtle way of asking for a vacation for his men, presumably without pay? Why should the entire orchestra desire a leave-of-absence at the same time? In the semi-feudal environment of the time, any collective action of this kind was extremely unlikely.

A much more plausible version of this episode is found in a half-forgotten book, Aneddoti piacevole e interessanti, by an Italian musician, Giacomo Ferrari, published in the Italian language in London in 1830. Ferrari, who knew Haydn personally, tells a story of the Farewell Symphony that makes sense.

“At one time, Esterházy became dissatisfied with the musicians of his orchestra and ordered Haydn to dismiss them all, with the exception of the first violin and the harpsichordist. Haydn was compelled to obey, but was distressed by both the necessity of ruining the livelihood of so many people and the personal loss of experienced musicians. He decided to compose an instrumental fugue, and invited Prince Esterházy to hear the performance on a certain Sunday after Mass. The prince complied with his request. After the orchestral section played together, as demanded by the fugue form, the crafty maestro introduced a sort of coda with successive pauses so arranged that one instrument after another ceased to play. The fugue ended with the violin and harpsichord playing one note in unison. Prince Esterházy enjoyed the composer’s joke so much that he told him to retain all the players on their jobs.”

Quintet – in Four Parts

Haydn biographers have often wondered why he never wrote a string quintet. A partial answer to this is provided by Giacomo Ferrari in his anecdotes. He writes:

“Prince Lobkowitz asked Haydn why he had never written an instrumental quintet. The answer was that he did not wish to have a work of his suffer comparison with the celebrated quintets of Mozart which he regarded perfect. ‘Never mind,’ said the Prince. ‘Write a quintet for me and I will remunerate you handsomely.’

‘The famous maestro set to work, and after a short while delivered the manuscript to Prince Lobkowitz. Glancing through the manuscript, Lobkowitz noted that only four staves had been filled, with the fifth left empty.

“‘Dear Haydn,’ he said, ‘you must have forgotten to put in the fifth part.’

“‘No, Prince. I left it for Your Highness to fill in. I could not compose anything appropriate myself.’”

Lobkowitz must have well understood the subtle irony of Haydn’s gesture. He certainly never attempted to fill in the missing part. It is not known whether the four-part quintet eventually became a legitimate string quartet.

Unopened Letters of Mrs. Haydn

Haydn was separated from his termagant wife for a long time. A friend, calling on him, noted with astonishment a pile of unopened letters on the composer’s desk.

“Oh, they are from my wife,” Haydn explained. “She writes me monthly, and I answer her monthly. But I do not open her letters, and I am quite sure that she does not open mine.”

Haydn and the Dog

While in England, Haydn visited his friend, Venanzio Rauzzini, an Italian musician who had settled in the town of Bath as bandleader and singing teacher. Rauzzini spoke of a recent bereavement: his favorite dog, Turk, had died. Rauzzini had buried the dog in his garden and had inscribed on the tombstone: “Turk was a faithful dog, and not a man.” Haydn was so impressed by this story that he composed a “perpetual” canon using for the text Rauzzini’s epitaph. The music of the canon is in existence; but the oft-told story that it was engraved on the dog’s tombstone is apocryphal. Inquiries at the office of the superintendent registrar of Bath have brought the information that Rauzzini lived at 13 Gay Street, in a house known in his time as Perrymead Villa. But there exists no vestige of the faithful Turk’s last resting place. Whether the tombstone was actually put up by Rauzzini must remain an insoluble mystery.

Mozart’s Program

Besides being an estimable musician, Mozart’s father was also a shrewd business man. When Mozart was a child, his father exploited his public appearances with all the sensationalism of which the eighteenth century was capable. The program which Mozart and his sister presented in Frankfort in 1764 (the text of which was prepared by the father) came to light in 1892.

“My daughter, twelve years old, and my son of seven will execute the concertos of the greatest masters on several kinds of pianos, and my son on the violin likewise. My son will cover the fingerboard of the piano with a cloth and play as if it were uncovered. He will guess, both standing near or at any distance, and name any sound on a piano, on a bell, or any other instrument. In conclusion, he will improvise as long as desired, both on the organ and the piano in all keys, even the most difficult, as anyone may choose.”

Mozart’s Musical Joke

Mozart possessed a healthy sense of humor. One of his compositions, named A Musical Joke, was intended to ridicule inexpert village bands. In it, there is a violin cadenza containing a whole-tone scale; there are parallel fifths in defiance of all established rules. As a climax, the piece ends in several different keys.

Nowadays, these harmonies are no longer funny. The whole-tone scale is part and p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- I Incidental Music

- II Not to Be Found in Authorized Biographies

- III This Modern Stuff

- IV Musicians Are Like That

- V Red, White and Blue Notes

- VI The Carnival of Animals

- VII Verse and Worse