1

STREET AND STAGE

The importance of public display in seventeenth-century Paris is attested by the diplomatic and political spectacles which from time to time marked the life of the capital and, indeed, by the planning of the open spaces which were required for such events.1 But if Peter Burke is correct in describing Louis XIV’s France as a ‘theatre state’, the term is justified beyond the court in the forms of daily life, trade and amusement. Molière would have known the display and performance in the market place, where the show was offered in its own right on the trestle stage put up on the Place Dauphine, or the Pont Neuf, or in the booths of the town’s two ancient fairs. For most of the population, it must be remembered, theatre meant theatre of the street.

For Molière the example of street theatre could have been inspirational, and he would have had every opportunity to see the players of a living tradition of popular French and Italian farce. The paintings and engravings of the early part of the century depict a range of performers, stages and the trade that accompanied performance. Such actors worked close to the public and addressed their audiences directly in the market place or the fairground. Their stages were set up beside the other sellers of wares in public places already pressured by the influx of commerce and the circulation of goods. The impact of these traders was resisted by the municipality, but without effect. In 1666 Gui Patin, the Parisian physician, was writing about the inadequacy of the legislation that restricted them:

They are beginning to put into effect the previously agreed policy against the sellers, dealers and cobblers who encumber the public way, because they want to clean up the streets of Paris; the king has said that he wants to do to Paris what Augustus did to Rome.2

Throughout the century measures were introduced to improve the physical state of the city, increasing paving, and regulating the street as a place of exchange.

If the peddler represented for the authorities an irregular and dubious trader, likely to gull the innocent and misrepresent his wares, this was because entertainment was all too natural a part of his function. Commodities never change hands without a flow of information, and in the seventeenth century market presentation was at a premium. In everyday life the market place was the principal vehicle for the exchange not only of goods but of news. Pea-shellers, for example, were notorious gossips, like the present-day taxi-driver or hairdresser, delivering a service which could be supplied only in the presence of the customer.

The passage of information depended on public space. In an age where a relatively small proportion of the population could read, effective widespread publication depended upon human presence and the human voice. Town criers were part of Parisian street life and, although official announcements were made via a system of posters, affiches, or, for royal legislation, placards, placed at appointed sites, they were confirmed viva voce by the juré-crieurs du Roi, heralded at stopping places by three juré-trompettes. Only then was legislation binding. At particular sites, posters, including those for theatre performances, were displayed, and discussed for the benefit of those who could not read, but might consequently be all the more willing to attend. A quasi-theatrical display aided daily exchange and intercourse in the city. The pictorial sign, and the live presentation of events, far outweighed the printed word. Movement about the city was negotiated by means of landmarks and signs: churches indicated parishes, and if the correct parish could be found and the street discovered by enquiry, the individual house might be identified by its painted sign. (Molière was born at the pavillon des singes, named after the sculpted and painted pole at the doorway.) So important and widespread was the trade sign to the merchant or artisan that an attempt had to be made ultimately to regulate its size and positioning.

Another form of advertisement was the creation of the events through performances, particularly associated with the street seller’s wares. The dialogue between trader and public grows into that of the seller and his assistant: a cross-talk act still familiar today with market and fairground traders. A development of this is the professional entertainer, and then the small company, standing alongside the salesman, showing in a living drama the nature and effects of the products on sale. The chief instance of this is the sale of medicines, where the miraculous powers of the nostrum can be demonstrated by the players. Through the first half of the century, the engravers’ workshops were active producing images of celebrated opérateurs who entertained and sold, aided by their band of players. The most considerable among them maintained a small acting company, including players who went back and forth between street theatre and the drama of the playhouses. Italian commedia dell’arte players are evident on the stages of mountebanks in Italy, France and the Low Countries, and French players could surely find similar employment should the need arise. When the theatres were closed in Lent, street theatre escaped regulation, and at all times it offered low overheads and a guaranteed audience.

Street performance figures notably in the career of the farceur, Guillot-Gorju, famous in the 1620s, and from whose widow, it was later maliciously rumoured, Molière had purchased the secrets of his success. Having first qualified in medicine, he performed with a charlatan, but was then recruited to the comédiens du roi at the Hôtel de Bourgogne. After a period of some years, it is said, he resumed his career in medicine. The actor Des Lauriers played as the farceur Bruscambille at the Bourgogne, where his speciality was to deliver comic addresses to the crowd at the beginning of the performance, while at other times he worked in the street with the opérateur Jean Farine. His act was popular enough to be published in 1658 (or possibly it was the name which was capable of selling the material).

Figure 1.1 Street theatre: l’Orviétan, the seller of remedies. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris

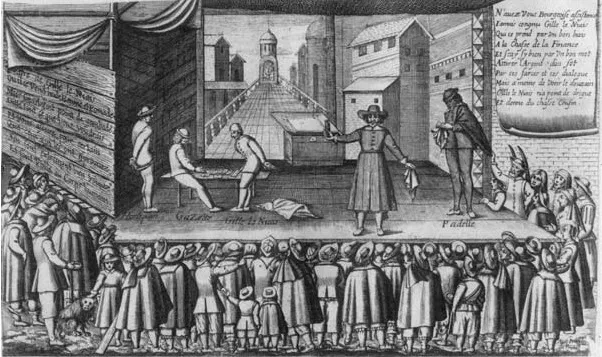

Figure 1.2 The company of Gilles le Niais. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris

Similarly the actor working with the opérateur Desiderio Descombes published a volume in the guise of his stage character: Les Rencontres, fantaisies et coqs-à-l’âne facétieux du Baron Grattelard.

The miracle remedy, orviétan, is so famous that it gives its name to the seller, L’Orviétan, seen in a popular print (Figure 1.1) accompanied by at least two characters from his native Italian commedia: a Polchinelle, and a Brigantin, whose appearance suggests a relationship to Trivelin or Harlequin. A third character, l’Aveugle, seems more appropriate to native taste. The show is lively and full of movement: l’Aveugle is bated in some way while l’Orviétan controls the audience reaction. The setting is simple but, as the artist makes clear, solid. A closed, covered set stands on a substantial trestle stage, with space for a small group of privileged spectators, while the passing public stops below in the street, or goes on its way. In the engraving of Gilles le Niais (Figure 1.2), the setting goes as far as a scenic drop, and one may see, thanks to the artist, the heavy timber construction of the staging. Again the acting is rendered in lively fashion, with the stupid Gilles, wearing his characteristic closely fitting cap, following intently the progress of a card game.

In most cases the prints of street theatre insert into the composition some brief verse explaining the fun, often in the form of a street wall-poster. It would appear that not only were these theatres substantial semi-permanent structures attracting the casual passer-by, but they also promoted themselves by means of publicity.

The classic engraving of the famous company of Tabarin and Mondor playing the Place Dauphine (Figure 1.3) shows a simple trestle stage with a curtain serving as backdrop and discovery space. In a double act the star actor Tabarin enlivens the opérateur Mondor’s presentation of a product for which ambitious claims have to be communicated. His name, ‘mount of gold’, reflects the exquisite action of the nostrum, w...