This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This examination of a phenomenon of 19th century planning traces the origins, implementation, international transference and adoption of the Garden City idea. It also considers its continuing relevance in the late 20th century and into the 21st century.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Garden City by Stephen Ward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE GARDEN CITY INTRODUCED

Stephen V. Ward

During the late 1980s and early 1990s a remarkable phenomenon has begun to emerge in planning circles in several parts of the West: the rediscovery and re-examination of the garden city idea. Despite the prevailing thrusts of Western politics in the 1980s away from collectivist solutions and government planning towards the market-led regeneration of existing urban concentrations, the garden city has crept back onto the planning agenda. In Britain there has been an extraordinary surge of interest from private housebuilders, together with a spate of conferences, professional and propagandist reports and official pronouncements. And, as if to emphasize the seriousness of all these moves, they have even been brilUantly evoked and satirized by the distinguished and popular novelist, John Mortimer (1990). However the scale of this British revival in the garden city/new community movement is unique. In no other country has it achieved the momentum it has in Britain, though we can point to some similar signs in other parts of Europe and elsewhere.

Some of this can no doubt be dismissed as a mere commercial appropriation of the garden city movement's traditional credibility and legitimacy to make money out of property development. (Certainly John Mortimer's mythical Fallowfield new country town is largely represented in this way.) Nostalgia for quaint diagrams and phraseology also plays its part.

But beneath the explicit signs we can detect something rather more fundamental that goes beyond these superficialities. Reviewing the emergent social and environmental agendas of Western societies in the late twentieth century, it is striking how many of the separate elements of the garden city idea they embody. The progressive rejection of the big city; the desire for small town living and working; the search for real involvement in common affairs; and, not least, the adherence to a new ‘green’ lifestyle represent widely shared social values. Although few people would explicitly articulate such values in terms of the garden city, it is this or something very close to it that their complete realization implies.

If this line of reasoning proves to be even partly correct then the garden city idea, whether under its own or another name, is set to become a much stronger element in the planning debates of the 1990s than it has been for some decades. The danger is that such debates will be conducted with only limited awareness or understandihg of what the term garden city and the diverse tradition which has derived from it represent. Much propagandist vitriol has been expended in past debates about the garden city idea, largely contesting the legitimacy of this or that interpretation. This book does not start from such partisan premises and is intended to inform and enlarge present debates by examining the development and diversification of the garden city tradition on an international basis. It is, to a large extent, a work of planning history though written with a strong sense of the present and likely future.

Its themes reflect the tremendous historical potency of the garden city as an idea about urban and social reform. This introductory chapter, as well as introducing the individual contributions, explores the conceptual history of the garden city. It shows how, despite the apparent clarity and coherence of the original vision, the garden city idea and the movement which developed to advance it showed considerable flexibility in practice. By 1910 it had already proved to be an extraordinarily rich source of concepts that were adopted and technicalized by the newly emerging international practice of town and regional planning. The fact that the original garden city idea was capable of being taken apart and applied selectively was of huge significance in allowing the idea to persist and spread. It permitted parts at least of the idea to take root in widely different economic, institutional, cultural and aesthetic contexts. However this tendency to diversity, although an important symptom of the potency of the garden city idea, does not alone explain it. It was the parallel persistence of purer (though not necessarily pure) versions of the idea that prevented a complete fragmentation of the movement and produced the creative tensions that gave the tradition its characteristic intellectual vigour. It is with the original vision that our introductory survey of the conceptual evolution of the garden city idea begins.

ORIGINS

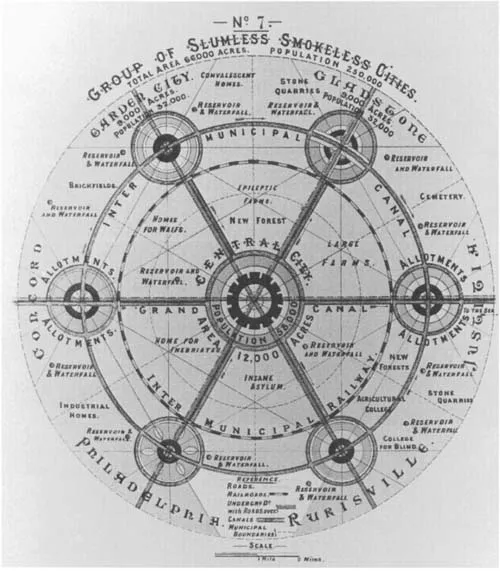

The origins of the garden city idea will be explored more fully in the next chapter, so we need give only the bare outline here: the idea was developed by Ebenezer Howard, an obscure EngUsh stenographer and shorthand writer. After much unpublished rehearsal during the 1890s, Howard's proposals finally appeared in print in 1898, in his book To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. What they offered was a comprehensive vision of social and political reform involving the gradual transformation of the existing concentrated cities into a decentralized but closely interrelated network of garden cities, collectively called the social city. Each individual garden city would have a population of 30,000, with a further 2000 in the surrounding agricultural estates. Development would occur on the basis of co-operative action and especially the collective ownership of land. This would allow the increase in land values that accrued from the development of the garden city to be realized by the community as a whole and used for the common good. However beyond this insistence on collectivism with respect to land, Howard avoided any wider rejection of industrial capitalism.

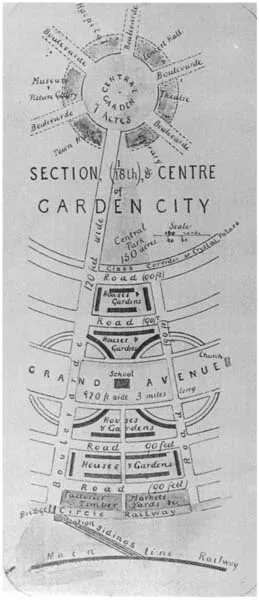

In general terms, none of the individual elements that made up Howard's ideas was particularly new. Howard fully acknowledged this, referring to early work advocating industrial and population migration, land reform and model communities. He saw his distinctive contribution as achieving ‘a unique combination of proposals’ (Howard, 1898, p. 102). To-morrow was largely concerned with the practicalities of developing and administering the garden city. Surprisingly, in view of what his idea soon came to represent, it dealt with the physical environment of the town fairly briefly and used highly simplified diagrams. However, more damagingly for his larger purposes, it also said tantalizingly little about the broad reformist goals which garden city development was intended to fulfil. Even before his ideas were published Howard, presumably unconsciously, had made an important decision which assisted the subsequent downgrading of his primary purposes and promotion of the secondary elements. This was the adoption of the label ‘Garden City’ instead of his earUer choices ‘Unionville’ and ‘Rurisville’ (Beevers, 1988, pp. 40–54).

Figure 1.1. Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928), inventor of the garden city and arguably the most important figure in the international history of urban planning.

The new term was not his own coinage and there is some dispute about its origins. It was certainly in use in the United States where Howard spent five years of his early manhood. Pre-skyscraper Chicago was universally known as The Garden City' at that time and this has led many commentators, including most recently Peter Hall, to claim that Howard almost certainly picked up the term from this source (Osborn, 1965, p. 26; Hall, 1988, p. 89). However Howard himself always denied this (Beevers, 1988, p. 7). A more likely source was the sociahst and artist WiUiam Morris who was using the term in the 1870s, laden with many of the same Utopian meanings that Howard now proposed (Henderson, 1967, p. 144; Naslas, 1977). Some support for this comes from Howard's view of Morris as one who (in common with Moses, Thomas More, John Ruskin and the Russian anarchist, Peter Kropotkin) failed only ‘as by a hair's breadth’ to give expression to the garden city idea (cited in Beevers, 1988, p. 17). But wherever the term came from, there is no doubt that its directness, simplicity and potent imagery helped to attract adherents when To-morrow was published. However the beguiling vagueness of the garden city label and its seeming emphasis on environmental concerns certainly made it the enemy of his wider purposes. Thus the possibility of divorcing means from ends was already apparent, and perhaps inevitable, even in the first edition of the book.

Figure 1.2. Howard's alternative to the concentrated big city, the social city was a network of garden cities around a slightly larger central city. This diagram was included in To-morrow but shown only in a partial form in Garden Cities of To-morrow.

GARDEN SUBURB REVISIONISM

The creation of the Garden City Association in 1899 and the re-issue of Howard's book in a slightly revised and re-titled form as Garden Cities of To-morrow in 1902 further intensified this subordination of social to environmental reform. So too did the initiation of the first garden city at Letchworth in 1903 (Miller, 1989a). While its power as a practical demonstration should not be underestimated, the demonstration was largely understood as a model environment not a model society. Serious compromises were necessary in the practicalities of developing the garden city and attracting capital. Howard's vital principle of communal land ownership was not implemented in a manner that approached his own ideal. A spirit of social experiment, evident in free thinking, vegetarianism, co-operative housekeeping and pursuit of the ‘simple life’ persisted in Letchworth for some years, but it encouraged Edwardian amusement rather than emulation (Miller, 1989a, pp. 88–111; Pearson, 1988).

Figure 1.3. Section of the garden city in an unpublished diagram from Howard's papers. It is mainly significant because it shows that Howard seems to have envisaged residential areas as rather conventional terraced rows of housing.

However this cranky image was to a large extent counteracted by the increasing involvement in both the Garden City Association and Letchworth of influential business and professional interests, personified by the respected London lawyer, Ralph Neville (MacFadyen, 1933, pp. 40–43; Buder, 1990, pp. 79–83). Such interests brought money, organizational skills and, above all, respectability to the movement. The patronage of important industrialists such as George Cadbury and the newspaper proprietor Alfred Harmsworth was crucially important in the estabhshment of a bridgehead of middle-class tolerance and sympathy (Sutcliffe, 1990, p. 262). They were immeasurably helped by the sheer quality of the residential environment which was created at Letchworth. The Arts and Crafts humanity of Raymond Unwin, Barry Parker and the other architects showed that the garden city idea, expressed at the level of the home and the residential environment, had a great deal to offer the kind of lower middle-class suburbanites who read Harmsworth's Daily Mail Significantly, residential development occurred on lines that were more generous than Howard had originally envisaged (Beevers, 1988, pp. 108–109). However he firmly approved of the larger plot sizes and the shift away from narrow-fronted terraced houses that this allowed.

As can be appreciated, these shifts brought further movement away from Howard's original conception. Both the widening base of support and the articulation of the physical form of the garden city had the effect of intensifying the emphasis on the environmental dimension. As far as private capital and respectable middle-class opinion were concerned, this was altogether less problematic than Howard's larger social reformism. Moreover, the loving attention that the architects gave to the residential environment added a new micro-dimension to the garden city idea that marked the beginnings of its conceptual and practical fragmentation as a holistic strategy.Thus the site and residential planning ideas of Unwin and Parker began to acquire an identity of their own, independent of the total garden city package.

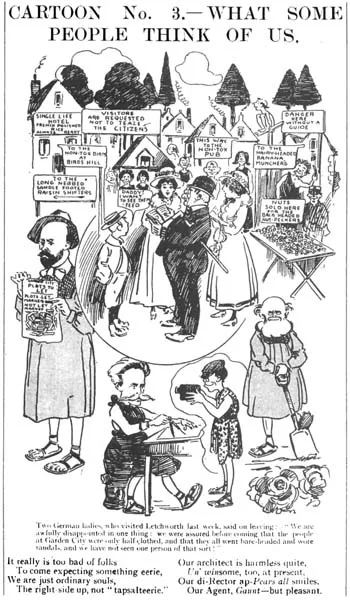

Figure 1.4. Early Letchworth was pervaded by a spirit of social experiment, attracting much ridicule from respectable Edwardian society. The lower part of the cartoon includes three important figures in Letchworth's early development: Walter Gaunt, offering plots to let, Raymond Unwin at his drawing board and Howard Pearsall, engaged in cultivation.

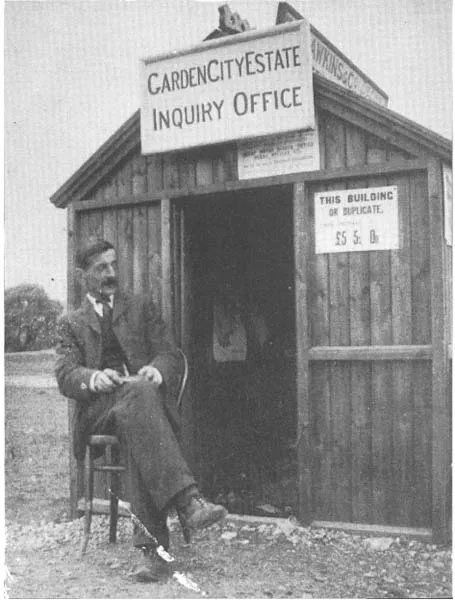

Figure 1.5. The realities of creating Letchworth were rather more prosaic than either Howard or the cartoonists implied. The pace of early growth was slow.

Figure 1.6. Two cheap cottage exhibitions were organized to promote the town. This attractive design is taken from the cover of the catalogue for the second, the Urban Cottages Exhibition, held in 1907.

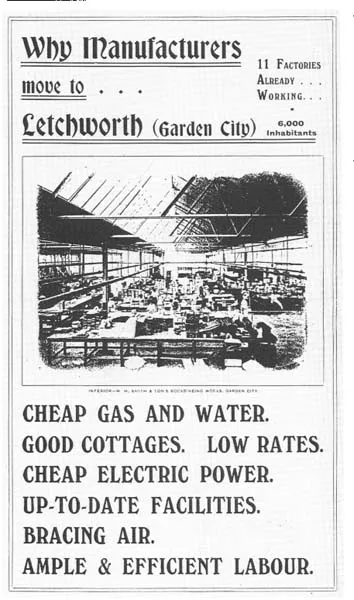

Figure 1.7. Attracting industry to Letchworth was also a problem. Under Walter Gaunt (see figure 1.4) an active promotional campaign was begun. This example dates firom c. 1909.

From about 1906, or perhaps even earher, this fragmentation began to be formally and consciously pursued by the garden city movement (Culpin, 1913, pp. 10-11). Increasingly the efforts of the Garden City Association were to be devoted to the apphcation of garden city principles to existing towns. The firm establishment of Letchworth was proving difficult to achieve and the chances of creating more freestanding garden cities seemed bleak (Purdom, 1963, pp. 11–30; Simpson, 1985, p. 35). In such circumstances the garden suburb and garden village appeared more reahstic objectives, capable of widespread apphcation. Within a few years many such projects were underway, most famously at Hampstead Garden Suburb (Creese, 1966, pp. 219–254; Ashworth, 1954, pp. 159–164). These had the effect of drawing the garden city idea directly into the important arena of urban reform. In conjunction with other organizations and individuals, the movement began to play an important role in the formulation and consohdation of the new practice of town planning (Sutcliffe, 1990).

Meanwhile another strand of diversification arose through a growing international dimension. Translations of Howard's book and/or interpretations of what were taken to be his ideas soon appeared in France, Belgium, Germany, Russia, Japan and elsewhere (Read, 1978; Smets, 1977; Hall, 1988, pp. 112–122; Sutcliffe, 1981, pp. 41, 144–145, 149–150). We have noted how soon diversification and gradual change in the conceptual basis of the garden city occurred even in Britain. The trans-cultural transfer of the garden city understandably brought even great...

Table of contents

- Cover

- The Garden City

- Studies in History, Planning and the Environment

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1. THE GARDEN CITY INTRODUCED

- 2. English Origins

- 3. The French Garden City

- 4. The Japanese Garden City

- 5. The Nazi Garden City

- 6. The Australian Garden City

- 7. The American Garden City: Lost Ideals

- 8. The American Garden City: Still Relevant?

- 9. The British Garden City: Metamorphosis

- 10. The Garden City Campaign: an Overview

- Index