1

INTRODUCTION: MANY ROADS LEAD TO NGOs

After several decades in the wings of development practice and debate, non-governmental organizations—NGOs—have quickly moved to centre stage. The explosion of interest in them has come from different quarters: from academic researchers, development activists, multi- and bilateral donor agencies, and not least from society itself. In academia this interest is reflected in research programmes and a growing body of published work focusing on NGOs. Society’s interest is reflected in the rising contributions to NGOs, and the growing frequency with which representatives from them are interviewed in the mass media. Some donor agencies, such as the World Bank, now have departments specially responsible for NGOs, and departmental statements that emphasize work with NGOs. Certainly they and northern governments are channelling ever greater amounts of money through the non-governmental sector.1

In this introductory chapter, our purpose is to define the term ‘NGO’ and to chart some of the experiences and changes in development thinking that have led to this enthusiasm for NGOs. We will pick out certain lines of reasoning about the state, about civil society, and about technology, that have led analysts and donors alike to the non-governmental sector. Our specific analysis in the remainder of the book deals with NGOs and agricultural development activities, and part of this chapter deals with issues that have been specific to the agricultural sector. However, much of the interest in NGOs stems from debates on development theory and policy, and so much of this chapter is given over to this wider arena.

As we will see, the reasons for this surge of interest are diverse, and not always mutually compatible. For some, NGOs are in the vanguard of an alternative mode of development that is fundamentally different from today’s neo-liberal orthodoxy; other lines of reasoning see NGOs playing roles within the existing neo-liberal framework. Many roads lead to NGOs.

It would be convenient if we were able to apportion these different perspectives on NGOs to specific institutions. Unfortunately, such analytical tidiness is impossible. Similarly, there are no easily definable, mutually exclusive neo-liberal, or post-marxist positions on what NGOs should contribute to development. In part this is indicative of the diverse views that tend to coexist within any one institution or school of thought. But it is also the effect of a shared uncertainty about how to define, and then implement, successful development. Thus, in an institution, such as the World Bank, that some might define as a bastion of neo-liberalism, we can also find an increasing willingness to argue that development should accord as much importance to human rights and democratic process as to economic growth (EXTIE 1990). Among radicals, the lines of the development debate are now far less clearly drawn than they were when ‘modernization and modes of production’ were counterposed (Taylor 1979; cf. Booth 1992). There is now greater willingness to recognize the potentially virtuous contributions of the private sector to development, the limitations of the state as a vehicle of progressive social change, and the need for serious consideration of economic efficiency in the delivery of development services.

At the heart of this blurring of lines is a need felt by many to rethink existing concepts of the state and the market, and what they can and should contribute to development. Experiences with both are mixed (Colclough and Manor 1991; Uphoff 1993). The excesses of state inefficiency, repression and corruption require a rethinking among those who previously assumed that socialism, or at least social development, would be achieved through public sector actions. On the other hand, nor have profit minded actors in the market shown much willingness to eradicate poverty, empower the poor, or even to invest productively in the wake of neo-liberal economic programmes.

This rethinking has stimulated reformed radicals and neo-liberals alike to look for a ‘third sector’ (Korten 1987) to alleviate poverty, strengthen civil society and promote efficient and participatory grassroots development in ways beyond the capability—or willingness—of the state and the market (Uphoff 1993).2 This ‘third sector’ has been found in the complex of voluntary, self-help and non-governmental organizations that have long been present in society. Some analysts come to these NGOs more interested in poverty alleviation and efficiency, others more concerned with empowerment and a stronger civil society, and others with an interest in ‘green’ development. They therefore place particular stress on different roles this third sector can play in development. But, as we shall see, the different perspectives also have much in common.

The uncertainty in development thinking is played out in a parallel uncertainty and multiplicity of views about what NGOs should contribute to development, as we shall suggest below. A specific aspect of this uncertainty—and one which was bound to arise from a fundamental reconsideration of the roles of state and market— concerns the relationship of NGOs to the state. We will return to this at the end of the chapter. First, however, after making a few comments on the definition of NGOs, we chart several areas of debate that have identified special roles for NGOs in (i) reforming the role of the state in development, (ii) supporting the self-managed development actions of grassroots groups, and (iii) making agricultural technologies more widely available, and more environmentally sound.

WHAT ARE NGOs?

Many roads may be signposted ‘NGOs,’ but there is considerable confusion in both the literature and among policy makers as to what we mean by the label NGO (Munck 1992). Authors such as Clark (1991) tend to use the label NGO all inclusively. Clark (1991:34–5) distinguishes six categories of organization (relief and welfare agencies, technical innovation organizations, public service contractors, popular development organizations, grassroots development organizations and advocacy groups and networks), but calls them all NGOs. As he himself says, such all inclusiveness can make the term almost meaningless. Part of the problem is that the classification does not fully differentiate between the function, ownership and scale of operation as part of a sub-categorization of these organizations. As a result, everything from a neighbourhood organization concerned with better lighting through to an organization operating globally, such as Oxfam, are equally labelled ‘NGO’.3

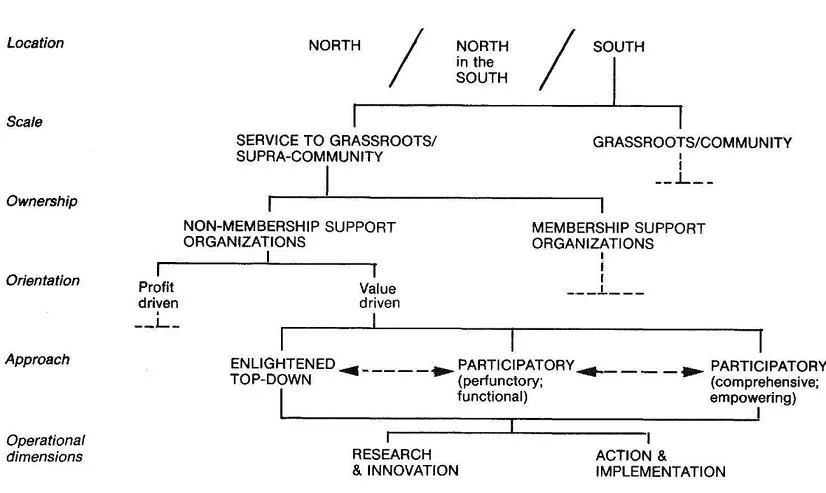

A first step in classifying these groups is to distinguish according to their origins (Figure 1.1). Are they northern NGOs that have activities in the South, or the southern-based branches or affiliates of these that operate with a high degree of autonomy, or indigenous South-based organizations? Within these last two categories, there are grassroots organizations (communities, co-operatives, neighbourhood committees, etc), organizations that give support to the grassroots, and those that engage in networking and lobbying activities (these functions are not necessarily mutually exclusive). Among these, some are North-owned (e.g. field-based Oxfam programmes), others are indigenous to the South. Most of our material deals with indigenous groups, particularly in Latin America. North-based organizations are proportionately more significant (and national NGOs correspondingly less so) in Africa, and so the African material presents more evidence on North-based groups operating in Africa.4

Among the organizations in the South, it is important to distinguish between them according to the nature of their relationship to the rural poor, and their staff composition. On the one hand are those organizations that are staffed and elected by the people they are meant to serve and represent (such as farmer organizations). Following Carroll (1992)5 and Fowler (1990), we call these membership organizations. Non-membership organizations are, by contrast, staffed by people who are socially, professionally and at times ethnically different from their clients. Similarly, the two types of organization have different relationships with the poor who are members of the former, and clients of the latter.

Membership and non-membership organizations can each engage in both advocacy activities and development actions in which they give services to the grassroots. Many combine the two sorts of action, though generally specialize in one or the other. Again, our emphasis has been on the service organizations, although some such as CLADES and KENGO are more engaged in advocacy and networking activities.

Figure 1.1 NGOs: diversity in the crowd

Source: Bebbington and Farrington(1992); discussions with Alan Fowler were also helpful in producing this figure.

Talking about the organizations that give services to, or lobby on behalf of their clients, Carroll (1992) combines questions of function and ownership, and distinguishes between ‘membership support organizations’ (MSOs) which are staffed and elected by their clients, and ‘grassroots support organizations’ (GSOs) which are professionally based and in some sense independent from grassroots control. This distinction is important, for the two sorts of organizations have differences in a number of dimensions, including:

- Claims regarding how far they represent grassroots concerns;

- Their management styles and stability (elected staff are more likely to change);

- Their professional competence;

- The directions in which they are accountable (especially the difference in how far they are accountable to donors and the rural poor);

- The social networks to which they have easy access and from which they are able to draw down resources and contacts.

There is a strong a priori case, often put emotively, to be made for working with membership organizations if democratic forms of grassroots development are our goal. We too would endorse that idea as a long-term goal, and have written about it elsewhere (Bebbington et al. 1992; 1993). Similarly, many GSOs state that their primary goal is to strengthen such organizations and ultimately pass control of projects to them. However, for reasons we will elaborate below, there are also grounds for guarding against optimism about membership organizations (cf. Carroll 1992). It is for this reason that in this book we have focused primarily on GSOs, although as we use the term ‘NGO’ in the text, our main referents are both GSOs and MSOs.

RETHINKING THE STATE

Much of the interest in NGOs has been generated by a disappointment in the past performance of the state. This poor performance has had economic and political dimensions. There have been economic concerns about the inefficiencies created by the state’s intervention in the economy, including its implementation of development programmes. Equally, there have been political concerns that many states have not been accountable to society, and indeed have been more interested in controlling and moulding society to suit their own interests, than in responding to the needs of that society.

Problems of efficiency

Traditionally, proposals for development programmes have assumed that the state and its many agencies were the vehicles through which projects and policies would be implemented—even if the understanding of how the state operated was often both weak and naive (Long 1988). The dominance of such state-centred thinking and action originated in some cases from Keynesian and import-substitution models of development in which the state was given the role as main protagonist in seeking to expand domestic markets and domestic capacity for industrial and agricultural production, and in breaking the dependency on export markets. In other cases, particularly in Africa, the state became the protagonist in the post-colonial project of nation building and self-determined development.

In the agricultural sector, the effect of this state-centred strategy was to litter the institutional landscape with parastatal marketing companies, agrarian banks, land reform agencies, public institutions for agricultural research and extension, irrigation agencies, rural development programmes and many more. If field researchers wanted to know about development programmes they almost instinctively went to the state agencies.

This growth of the state and the proliferation of its institutions (Martínez Noguiera 1990) brought with it a number of inefficiencies that caused growing concern to policy makers, and particularly to donor agencies—even though it had been those same agencies who in earlier years supported these institutional developments. Overall the growth of the state and struggles to influence its decisions led to inefficient allocation of resources at a national level, and particularly between rural and urban sectors, and private and public sectors (Krueger 1976; Lehmann 1990). The cost of sustaining the state structure, aside from implementation costs, diverted resources from other potentially more productive uses. Furthermore, many argued, decision makers in those institutions made policy choices that were urban-biased, motivated by institutional, political and even kinship interests, and hence had negative impacts on the rural sector (Bates 1981; Corbridge 1982; Grindle 1986; Hyden 1983; Lipton 1977).

In addition, many argued, the intervention of the state—in markets, pricing policies, and programme implementation—brought further inefficiencies (Krueger et al. 1991). Parastatals that were not subject to market forces had excessive operating costs, and their payments to producers were typically erratic in timing and quantity. This in turn generated further costs, as producers dedicated resources to evading the system (e.g. by smuggling) or simply withdrew from the market (Hyden 1983). In rural development projects, the tendency for state institutions to centralize decision making led to growing classes of urban-based functionaries, hierarchical decision-making and so reduced flexibility and responsiveness. This easily led to inappropriate and simply slow programme implementation at a local level (Barsky 1990). The biting crisis of public sector finances in the 1970s and 1980s aggravated these problems as resources were spread ever more thinly leaving public institutions without the materials and funds necessary simply to sustain operations. Public sector agricultural research institutes began to cut funding for field work, and supplies of materials for work-on-station remained unreplenished.

These difficulties were compounded by personnel problems. Institutions were often used for political patronage, to deliver resources to politically favoured areas, and to give jobs to party members and other clients (Hyden 1983). The problems of low motivation and commitment that inevitably arose were compounded by falling real wages in the public sector which led many to leave their jobs, take long periods of paid leave, or simply use the jobs as a basis on which to do other work as consultants (or taxi drivers).

In the 1980s, donors not merely withdrew from the earlier models of state-centred development; they made them the object of attack by an armoury of policy reforms. As part of the general packages of structural adjustment, the IMF and the World Bank have set the trend by demanding public sector reforms centred on reduced levels of expenditure, public sector restructuring, and state withdrawal from market and indeed project interventions (Moseley et al. 1991). Many bilateral donors linked their aid to these reforms—governments had to bite the multilateral bullet before receiving any bilateral bandages.

Before we demonize the donors too much, however, it ought be said that public sector retrenchment often merely formalized a de facto situation in which the state had already collapsed and was doing little or nothing of significance for the middle and lower income groups. Either way, these policy changes stimulated the search for new mechanisms of service delivery.

In certain ins...