![]()

Chapter 1

Food and Drink

The basic elements of a cognitive theory of food and drink are presented in this chapter.

What is Food and Drink?

Food, in one sense, is any material that an individual seriously regards as edible. Drink similarly might be defined as any fluid that is considered by some people to be potable.

That 'psychological' definition of food and drink is used in this book. This however is not to deny the scientific legitimacy – and the commonsense too – of the established definition of food as bodily sustenance. Neither is it to discount in any way the social and indeed moral issues about what really should count as food and hence as a real need for food.

The conventional scientific concept of food is restricted to its biological function. Food is material that can be shown to be nutritious. That is, its ingestion is necessary for survival, for good health and for growth of the young. Nutrients are those chemical compounds in foods that in some instances are essential to health and even to life for a given species. Other nutrients help to sustain the normal functioning of tissues but the particular compound is dispensable and other compounds can serve the functions instead.

Insufficiency of nutrients in the foods and drinks in the amounts that people can obtain is one of the major ethical challenges and political problems that the world currently faces. Yet even where the technology exists to produce more food, there often remain great ecological, economic and cultural difficulties just in emergency feeding of the hungry, let alone enabling famine-stricken groups to produce and trade enough to feed themselves. So a purely biological concept of need for food is amply sufficient to make heavy demands on our social and personal understanding of humanity.

Nevertheless, the most nutritious material hardly counts as rood if nobody will eat it. As the saying goes, one person's meat is another person's poison. Even the starving are reputed to have refused foodstuffs that had never been in their diet.

Moreover, some of what richer peoples regard as food is nutritionally unbalanced or even inadequate. We certainly do not need to eat all the items of food that we do in order to survive or to be healthy. So a strictly biological definition of food would not be realistic to human behaviour, nor probably for other species.

Further to the point, hunger and thirst are personal states of wanting to eat and drink materials perceived as foods and beverages. However, these appetites are not limited to the necessities of physical existence. It is a truism in applied nutrition that people do not eat nutrients; they eat foods. This means that they don't usually think of what they are eating in terms of the nutrients in it. The point of a psychological and social definition of food and ingestive appetite is that a substantial part of consumption has nothing to do with nutritiousness, even indirectly or unconsciously. Some of the causation of the ingestive behaviour is unconnected with nutrients. It may even be anti-nutritious. That is, some of the effects of eating may be unhealthy and the eater is aware of the possibility. So the purely biological definition of food and drink and of hunger or thirst must be wrong. Anti-nutritious ingestion only proves the point, though. Eating and drinking not motivated by physical needs can be neutral with respect to health. Indeed, the main point of recognizing food as perceived ingestibles and not just nutrient mixtures is to correct the intellectual and political error of treating the motivation to eat and drink as relating only to benefits to the body or its detriment.

The German language draws a distinction between Lebensmittel (the stuff of life, normally translated food) and Genussmittel (literally, pleasure material, meaning a luxury, including a food item that is a treat.). One might argue whether sugar or alcohol was Lebensmittel or Genussmittel but this is in danger of confusing biology with moralizing. Both these substances are sources of energy, which we all certainly need in substantial minimum quantities. They constitute a part of the diets of many people who are eating entirely healthily. Foods and drinks containing sugar or alcohol are among the objects of ordinary appetite; they include both staples and luxuries,. In such contexts, sugar and alcohol can contribute a great deal to the pleasures of eating and drinking. Yet neither substance is nutritionally necessary. Also, of course, certain uses of sugar or of alcohol can be unhealthy or unsafe and a risk to others as well. Yet an essential nutrient too can be poisonous, when consumed in excess.

Thus, we should go further in 'psychologizing' the definition of food. Even the biological concept of food cannot be reduced to a chemical definition, as a mixture of nutrients. Whether a substance is nutritive or not is in part an inherently behavioural matter. It sometimes depends not only on what is eaten but also on how much is eaten when and in what circumstances.

These are some reasons for broadening the definition of food to materials that are perceived and treated as foods and drinks by individuals. This approach could apply to members of other species whose behaviour is complex enough to justify the ascription of such perception. Also, in the human case at least, this definition is social because much of the content of individual perception depends on the culture within which the person operates. Finally, this psychosocial construct of food and hunger does not exclude the biological concept; rather it encompasses it. After all, eaters and drinkers often believe that their bodies need the calories, the water and sometimes other constituents of what they are consuming – and generally speaking those beliefs are broadly correct. So the psychological definition as a matter of sociological fact partly presupposes lay concepts of nutritional function and thereby approximates to the biological definition.

How Does the Mind Work in Eating and Drinking?

The theoretical position underpinning the cognitive approach of this book is that hunger and thirst are motives driven by recognition of similarity (like indeed any learned motivation). The basic theory is that an individual's disposition to eat or drink in a sufficiently familiar situation is inversely proportional to the distance of that situation from the most appetizing version of those circumstances for that person (or animal). The same theory applies to positive emotions towards the foods and drinks that are available there and then or even merely thought of or pictured. Also, an active inhibition of eating or drinking and negative emotions will be as strong as the situation is close to a learned sating or averting of appetite for food or drink.

This is a quantitative theory of the cognitive processes of hunger and thirst that in fact applies to all learned behaviour and experience (Booth, 1994). Such linear control by similarity to norm has always been presupposed in a qualitative form by experimental and social psychologists and in statistical form by psychometricians (Glymour et al, 1987). Mathematical psychologists have recently been clarifying this common foundation to the diverse streams of psychological research (e.g. Ashby and Perrin, 1988; Macmillan and Creelman, 1991). However, the simplest conceivable ways of measuring this mental causation within an individual's behaviour have been developed over the last decade for the appetite for food (Booth, Thompson and Shahedian, 1983).

Another way of summarizing this cognitive approach to eating and drinking is to say that the desire to consume an item depends on recognizing how close it is to the ideal that the individual has acquired for those circumstances, When the social situation and bodily state recur where the consumption of an item having certain salient perceptible characteristics has been most reinforcing, the individual finds that item maximally attractive and entirely appropriate to consume.

This is not to deny the possibility of unlearned processes affecting behaviour and experience; it is simply to point out that they have to be treated as special eases which are least likely to be relevant with familiar foods in common sorts of situation. The obvious examples are infants before experience of eating accumulates and children or adults faced with cuisines or eating contexts that are, in important respects, unlike anything they have experienced before. These cases are rare and it has been a mistake to model theories of eating and drinking (or any other psychology) on people's or animals' responses to strange situations that are experimentally convenient to impose, such as drinks of plain sweet solutions or lots of food to eat within an hour or so of having filled up.

Thus the explanation of actions and feelings towards food and drink depends on the mental dynamics of recognizing appropriate situations for eating and drinking.

Psychology of Food Recognition

Food, whatever the definition, therefore provides major challenges and opportunities for psychology. Solutions to the fundamental and practical scientific problems about foods and drinks depend on finding out how we recognize such materials to be eaten and drunk and so can decide whether or not to select them.

As with so many of our everyday abilities, knowing that an item is a food and whether we like it or not comes so naturally and easily that it may be hard to see this recognition as an achievement requiring scientific explanation. Ask a creative cook, though, or a developer of new food products. They are likely to be all too aware of the practical consequences of designing foods and not understanding how people recognize what they want. Consider for yourself all that is involved in buying a supply of food for a day or more, choosing a meal from a service counter or a restaurant menu, or making up your mind how good the souffle or sponge-cake is that you have just cooked.

The Task of Recognition

An item of food or drink, like any other object, is perceived as an integral combination of features set at particular levels. That's quite a mouthful (in more senses than one). Nevertheless, it is a succinct summary of the apparent nature of the problem that we face in gaining a scientific understanding of how we perceive foods. Let's take this formulation in bite-sized chunks.

Some features are categorical or all-or-none. They can only be present or absent, like the stone in a plum or the brand name on a can of cola. Nevertheless, even a categorical feature is present at one of two levels: 100 or 0 per cent.

Many aspects of foods and drinks are graded in level, though. The feature may be there in larger or smaller quantity or size, such as cheese in a egg souffle and jam or some other filling in a sponge-cake.

In some cases, a graded (quantitative) feature can be absent or undetectable and the material is still perceived as being a food. A souffle without cheese is still a souffle and sponge-cake without jam is still sponge. In that sense, the distinction between graded and categorical features is not absolute.

Nevertheless, a cheese souffle must have some degree of cheesey flavour to it. A jam sponge is not a jam sponge without some jam. Yet the thickness of the jam layer(s) can be minimal or generous. In either case, it is still recognizably a jam sponge.

Yet could not the jam be so thin that it is not just unacceptable as a jam sponge but not even really a jam sponge at all? At the other extreme, could not one have so much jam and so little cake that it would no longer be a slice of jam sponge but a serving of jam, decorated with a sliver of sponge as a hat on top and kept off the plate by another sliver underneath, and not normally edible by itself? This switch between really sponge and really jam is a little like the reversal between the figure and the background shown by some ambiguous black-and-white diagrams. Figure-ground reversals are a subjectively dramatic illustration of a second major point about recognition processes, namely its holistic character.

A recognizable item is also perceived as a whole: it is an integral combination of features. The air bubbles in the souffle do not just sit alongside the softness and stickiness of the solid matrix, the cheesey aroma and taste, the almost white colour and the less pale yellow and harder egg at the surface. They are all inseparable parts of the one entity. Whether or not the whole is in some sense more (or less) than the parts, the recognizable item is certainly different from a collection of independent parts. The features interact or are combined in some fashion which is subtler than simply piling them up randomly in a heap or adding them together in a long line.

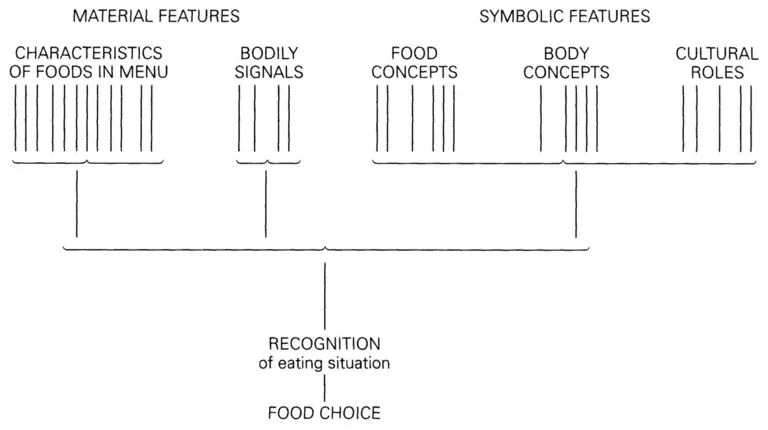

Figure 1.1 Combining perceptible features into recognition of a whole item.

This conception of the processes of recognition can be represented in a diagram (Figure 1.1). Each vertical line in the upper part of the diagram represents the possibility of perceiving the level of a distinct feature of the item in a particular context. A person in the act of eating or selecting a food item may not be under the influence of all the possible perceptual processes at that moment, but that person and others on some occasions may be influenced by each such feature that is perceptible.

The bracketing lines below, pointing down to the act that shows correct or incorrect recognition, represent the processes of combining whatever feature levels are perceived into an integral percept of the item as a whole. The rules of combination may or may not preserve the features in an obvious form. If they do not and the integral result bears no readily evident relationship to the elements, the whole will be psychologically quite different from a collection of its apparent parts.

Note also that a feature may itself be an integral of simpler features. In other words, Figure 1.1 can be nested. It represents one level of analysis and synthesis in a hierarchical system.

For example, the price on a food item may be perceived as a sign of high quality as well as a sign of expense to the purchaser's budget. 'Low in fat' may be taken to imply good for the heart and good for the waistline (and the two health benefits perceived in different proportions by men and women). The strength of a cup of coffee may reflect sugar and cream contents as well as levels of coffee solids. Such resolutions of a candidate feature into a combination of features might get rid of fuzziness in our scientific account of perception of price, the low-fat label or coffee strength. The fuzziness arose from hitherto poor identification of the more basic features underlying the higher-level construct. Perhaps the rule by which these sub-features are integrated into the named feature of the food item does not preserve those sub-features in a way that is obvious to the investigator or the food-perceiver. The feature emerges as a whole without obvious elements.

Despite these points, this approach may seem to be begging fundamental questions about the holism of perception and indeed the existence of such distinguishable features. What is being suggested, however, is that we try an approach to the mental organization within behaviour that is the same as the way in which any other son of phenomenon has been approached in modern science. Indeed, the broad principles of the psychology of recognition described above seem inescapable for any systematic quantitative investigation of functioning entities of any sort.

We attempt to explain the workings of the whole solar system, lithium nucleus, liver cell or national economy in terms of theoretically distinct causal processes that interact in a theoretically synthesized overall performance. We can go wrong in theoretical analysis and theoretical synthesis. So the initially obvious candidates for perceptual features may become fuzzier as we examine the behavioural evidence more closely. The rules of integration that we first hypothesize do not put any features together in a way that accounts for recognition very well. Nevertheless, in either case, we can look for more precisely defined features and more successful integration rules. If we discover some that explain existing data better and stand up well under further investigation, our understanding of the phenomena is improving.

Conscious and Preconscious Processes

An impression that there is no scientific problem about food recognition mechanisms may arise because so often it seems that we just recognize an item without consciously working out what it is. We immediately reach for the choice that we want among the array of items. The right name for the fruit or vegetable just pops into mind, without thinking through a list or a semantic tree or any sort of mental filing cabinet of which we are aware. In other words, much of the mental processing in recognizing a food never comes to attention.

This is true of many of our abilities to name common objects. Moreover, in the process of recognizing a relative or a famous person, let alone a bicycle or a knife, some of the mentation can never become available even to the most careful self-monitoring of one's thoughts and actions. Indeed, the perceptual processes of recognition of facial identity are so deep below consciousness that as yet cognitive psychologists have made almost no progress in characterizing what aspects of a face actually are used and how the mind puts them together, despite the obviousness of facial features and of variations in them and some successes at improving photofit techniques and describing the overall structure of face-recognition mechanisms.

Many who accept that recognition mechanisms are a scientific problem do not see it as a matter for psychology, however. They assume that only brain scientists can find out how we recognize objects in ways of which we are unaware. The assumption is that psychology is concerned only with conscious processes and perhaps also (or instead) with 'behaviour' in the sense of movements of the body and the physical events that the movements produce (such as the disappearance of food down the throat).

On this view, what people say is not anything that they perform with greater or less success. Rather, words are a window through which the hearer (or reader) can see directly and with certainty into the contents of the utterer's consciousness, at least if the speaker (or writer) is instructed in the maintenance of certain disciplines of 'intro...