![]()

Part 1

Theory and Method

![]()

1

Introduction

People are interested in news. Whether the news comes from other people or from the mass media, we like to know what’s going on—in faraway places or in our neighborhood—we want to be in the know. Of course not everyone is equally interested in general news, and people may be more interested in one topic than another. But an underlying interest is there. How could people fail to attend to an earthquake in their region, or to a cure for cancer or AIDS?

In part 1, we propose that all humans monitor the world around them in order to find out what occurrences, either threatening or hopeful, are important, and that we share this with many animals. Lasswell (1960, 118) calls this the surveillance function of the mass media. “In some animal societies certain members perform specialized roles, and survey the environment. Individuals act as ‘sentinels,’ standing apart from the herd or flock and creating a disturbance whenever an alarming change occurs in their surroundings.”

In human societies, these individuals may be town criers, gossips, or others who pass along information. In most societies, journalists also fill this role—acting as socially sanctioned, professional surveyors for the rest of us. While most people may survey the world for ideas, people, or events that have personal relevance to them, journalists tend to concentrate on the social realm. Journalists relate to the rest of us those things to which we should pay attention, but to which we do not otherwise have access.

The existence of the mass media is largely justified by this surveillance function, and while the mass media may be part of the economic and political systems, even this is a result of their role to give people the type of information in which they are more or less universally interested. Although news is a manufactured product and is subject to a wide-ranging set of influences (Shoemaker and Reese 1996), the basic form from which news comes is people’s innate interest in two types of information: (1) people, ideas, or events that are deviant (either positive or negative); and (2) people, ideas, or events that have significance to the society.

Early news media research has set the stage for investigating the definition of news by focusing on the news production process, including influences on journalists and their organizations. White (1950) created the first gatekeeping study by reviewing how, as a wire editor, Mr. Gates’s personal beliefs and knowledge of news routines influenced his selection of news items (see also Shoemaker 1991). Soon afterward, Breed (1955) wrote about how journalists are socialized in the newsroom, recognizing organizational policies and supervisors’ influences.

Several scholars discuss news as a socially constructed product. Molotch and Lester (1974) analyzed news items in terms of being “routine,” “scandal,” or “accident.” Tuchman (1978) explored the news-making process and found that the structure and labor division of news organizations influence the definition of news. Fishman (1980) focused on routines of local beat reports and found that journalists guide news by making decisions on their beat structure rather than on news values.

Phillips (1976, 88) fielded a participant-observation study of four news media organizations and reported that news practitioners do “not conceptualize their own experiences or place concrete particulars into a larger, theoretical framework.” Gans (1979) championed an integrated approach to news in his combination of a content analysis of television and magazine news with participant observation at four media organizations. Cohen et al. (1996) looked at the production, news content, and news reception in eleven countries in connection with the European Broadcasting Union’s News Exchange Service. Jensen (1998) and his colleagues in seven countries used content analysis, individual interviews, as well as household interviews to study themes that emerged in people’s thinking about the news.

Research on international news is primarily centered on how news about foreign countries is distributed and structured around the globe (Hester 1973; Malek and Kavoori 2000; Pasadeos et al. 1998; Sreberny-Mohammadi 1984; Wallis and Baran 1990). For example, content-based studies include Gerbner and Marvanyi’s (1977) analysis of foreign news coverage in selected newspapers in nine countries. Findings show that variation in the amount of foreign news coverage is correlated with political systems. Kim and Barnett (1996) reported that economic development is the most important determinant of a country’s place in the network of international news flow. More recently, Wu (2000) reviewed foreign news in thirty-eight countries and suggested that coverage is primarily determined by economics and availability of news sources.

The definition of news within different cultural settings is not always considered; however, some studies try to understand the meaning of news within the culture and how meanings are similar and dissimilar across cultures. Galtung and Ruge (1965) reviewed coverage of three international crises in four Norwegian newspapers and proposed eight “culture-free” and four “culture-bound” news values that influence whether an event will become a news item. Harcup and O’Neill (2001) reviewed twelve factors to present a contemporary set of ten news values: the power elite, celebrity, entertainment, surprise, bad news, good news, magnitude, relevance, follow-up, and newspaper agenda.

Shoemaker and Reese (1996) proposed a hierarchical model suggesting that influences on news result from individual news workers; the routine practices with which news is collected, transformed, and disseminated; the characteristics of news organizations; social institutions outside of the media; and social system ideology and values. Weaver (1998) expanded upon these ideas in his research on journalists around the globe.

Any way we look at it, people seem to have an innate interest in information. Furthermore, people’s interest in certain types of information tends to be the same, even while their interest in specific topics may differ. This book builds upon the primary idea that humans in all cultures and countries are basically interested in the two types of news information described already.

We wish to point out that this book—indeed, the whole project—is an example of the deductive model of social science research. This approach begins with theory, derives hypotheses from the theory, tests the hypotheses, and then revises the theory as necessary. In an ideal world, the deductive process continues until the theory is complete (or until scholars grow weary of it).

Although the deductive model is often taught, it is rarely observed in our literature. Journal articles, which usually allocate fewer than twenty pages, typically begin with some limited theoretical notions and test hypothesis, but the discussion is often too short for a comprehensive interpretation of the results and for proposals to change the theory in anything more than a “the next step ought to be” fashion. If scholars were able to immediately follow one journal article after another, showing how their theory has been revised, how new hypotheses are derived, tested, and so on, then we would probably have more and better theories in our field. Such a set of journal articles could eventually contain the theory in its entirety. But the world of scholarly publishing does not encourage the development of theory-driven research programs; manuscripts are judged as unique products and not as the second or third iteration in the logical and deductive process of theory building. The result is that theory construction is discouraged.

While we do not claim to have derived a complete theory of news and newsworthiness, this book does present the stages of the deductive process that we went through. Accordingly, chapter 2 presents the initial theory and hypotheses. The methodologies are presented in chapter 3 in which we discuss how in the first stage we selected ten countries for the study and how we completed quantitative content analyses of sixty newspapers and television and radio news programs for seven days across seven weeks. The second stage involved eighty focus groups in twenty cities, representing journalists, public relations practitioners, and high and low socioeconomic-status audience members. These groups were used to find out what type of information people want and, later, what sorts of news events they thought were most memorable. In stage three, we used quantitative data secured at the end of the focus groups, which asked people to rank-order newspaper headlines.

The hypotheses are tested in several ways across countries in chapters 4–7 and detailed within countries in chapters 8–17. In chapter 18 we interpret these results and conclude that not only are some of our original assumptions invalid, but also that a new theoretical model is needed. The new model includes the addition of a new concept and the redefinition of some old ones. Preliminary (because we didn’t want this book to have 600 pages!) tests of hypotheses from the revised theory are presented, as well as ideas for testing many more. Fortunately, it is much easier to demonstrate the deductive model in a book of 400 pages than in a 20-page article.

However, as in mysteries, we shall not give away the ending too soon. For readers who cannot wait, the description of the revised theory is in chapter 18. But since this book tells a story that is reinforced, country by country, even as the story evolves, the weight of the evidence can best be assessed after all the chapters read.

What’s news? Notions about this have been around before this book and will continue after it, but we hope that the opportunity we were given in this project will be followed by other scholars who will make this an even better theory.

![]()

2

Evolution and News

If you ask a journalist to define news, the journalist may reply, “I know news when I see it.” If pressed, the journalist will probably list a set of conditions that make people or events more newsworthy: novelty or oddity; conflict or controversy; interest; importance, impact, or consequence; sensationalism; timeliness; or proximity (Shoemaker, Chang, and Brendlinger 1987). If pressed further, the journalist may become irritated or impatient, because for the journalist the assessment of newsworthiness is an operationalization based on the aforementioned conditions. In other words, the practitioner typically constructs a method for fulfilling the daily job requirements. He or she rarely has an underlying theoretical understanding of what defining something or someone as newsworthy entails. To be sure, individual journalists may engage in more abstract musings about their work, but the profession as a whole is content to apply these conditions and does not care that the theory behind the application is not widely understood. Hall (1981, 147) calls news a “slippery” concept, with journalists defining newsworthiness as those things that get into the news media.

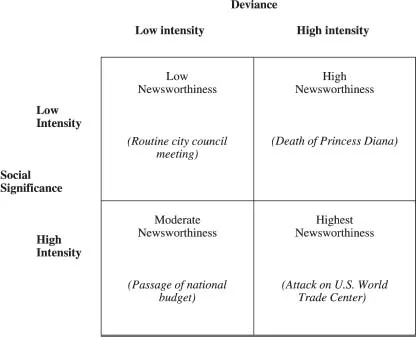

In the interest of developing a more theoretical explanation of how news is defined, we propose that people—and journalists!—are most interested in two general pieces of information about an event: how intensely deviant and socially significant it is. We propose that the intensity of these dimensions is positively related to how prominently a news item is presented in the mass media. We also propose that these two types of information interact such that if a news item is both intensely deviant and socially significant it will get the most prominent coverage (Shoemaker 1996).

Why Deviance and Social Significance?

Returning to the basic rules journalists use to identify news, we can see that some include elements of deviance and others of social significance. Later we define three dimensions of deviance. In general, we can discuss deviance as a characteristic of people, ideas, or events that sets them aside as different apart from others in their region, community, neighborhood, family, and so on. Deviance may be thought of as either positive or negative, but most deviance has a negative cast to it, as does most news. When journalists select something as newsworthy using deviance as an underlying reason, they are using the operational indicators novelty, oddity, or the unusual; conflict; controversy; and sensationalism. These indicators of news tell us about something different from our day-to-day lives. For example, when the former Princess Diana of Great Britain died in an automobile crash in Paris, the subsequent outpouring of sympathy and curiosity occupied the news for many days in many countries.

Later we present four dimensions of social significance, although it can generally be defined as that which has relevance for the social system—whether the social system is as large as the world or as small as a neighborhood. Journalistic criteria that involve elements of social significance include importance, impact, consequence, and interest. For example, when terrorists skyjacked airplanes to destroy the World Trade Center in New York City and to ram into the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., this was news of worldwide social significance. Although nearly every country in the world sent messages of condolence to the United States, another, perhaps more important, measure of social significance was a heightened feeling of exposure to terrorist attacks in many countries that do not have a history of much terrorism.

Comparing the death of Princess Diana with the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon shows us how the concepts of deviance and social significance may interact. Diana’s death was of little social significance outside of Great Britain and possibly even of limited significance there, since she was divorced from Prince Charles and no longer in line to become Queen. Her death—and in fact her life—was an example of deviance to most people. She was novel, controversial, and sensational. Her divorce involved conflict. On the other hand, the terrorist attacks in New York and near Washington, D.C. had economic and political significance as well as an effect on the general level of well-being of the public. Yet these attacks were also clearly deviant: airplanes targeting skyscrapers and causing them to collapse; thousands of people dying. And there was also deviance in that a fourth airplane—possibly headed for the White House—was not successfully skyjacked by terrorists. Passengers apparently overwhelmed the terrorists, even though the airplane still crashed, killing everyone aboard. Heroism is rare and therefore deviant.

We propose that deviance and social significance are separate predictors of newsworthiness, and that the combination of these two dimensions—when both have intense values—results in an accentuated level of newsworthiness. As Figure 2.1 shows, newsworthiness is highest when an event has both intense deviance and intense social significance, as was the case with the U.S. World Trade Center story. However, when the intensity of deviance is high and the intensity of social significance is low, newsworthiness is still high, as is the case with the story about Princess Diana’s death. On the other hand, when deviance is less intense, newsworthiness is lower, but the event may be moderately newsworthy if social significance is intense, as is the case when legislators pass a nation’s budget. The event is important to the country, but passing a budget is a routine activity of government. Finally, when both social significance and deviance are less intense, people, ideas, and events should be of the lowest newsworthiness, and most of them will never pass through the news “gate” to become a news story. In fact, most of the billions of events that occur each day fall into this category (Shoemaker 1991).

Fig. 2.1 Theoretical typology to predict how newsworthy events (also people and ideas) are perceived to be. Events are selected as news according to how intensely deviant and socially significant they are (adapted from Shoemaker, Danielian, and Brendlinger 1991, 783).

Biological Evolution

We propose that two forms of evolution—biological and cultural—profoundly influence the form news takes around the world. People have been biologically influenced to attend to deviance and culturally influenced to attend to social significance. The basis for deviance as a part of news is based in biological evolution.

Attention to certain ideas, people, and even...