1

Introductions: Our Book Authors and CS SFL Programs

In October 2017, local community and university members gathered at the Parkside1 Community Center adjacent to our university campus to celebrate an opening partnership between the local housing authority and our Youth Institute2. The maroon doors of the community center had been closed for several years, except for a summer sports program that, ironically, residents could not afford to attend. While scrubbing and painting the dusty walls of the center alongside children and adults of all ages and races, we felt it bizarre that we could see so clearly the enormous opulent buildings of the university—across the street yet, in some ways, a world away. Yet this juxtaposition of deprivation and wealth is pervasive in urban America. Ownership and dominion over urban space is a charged political and racialized process that has negative consequences on the lives and identities of underserved communities and their access to public places (Lefebvre, 1991; Soja, 1996). In other words, it is not a coincidence that the needs and interests of the Parkside subsidized housing community have been largely ignored by the city and the university even though it sits right downtown in the middle of everything. It's no stretch to think of the edifices erected around the community, massive and modern structures connected to commerce directly (hotels) and indirectly (a three-building expansion of the college of business) as encroaching both symbolically and literally. Parkside sits on valuable, and perhaps tenuous land. Similarly, many of our youth participants in the housing complex and other high-poverty neighborhoods in our small city experience life as precarious, often a dangerous terrain.

As critical literacy educators and community activists, we are called upon to engage in culturally sustaining approaches that “work within and against the systems they are a part of to disrupt or challenge ideologies of social reproduction through the literacy curriculum” (Simon & Campano, 2013, p. 22). The purpose of our book is to share our vision and enactment of what we call Culturally Sustaining Systemic Functional Linguistics (CS SFL) praxis. Our CS SFL programs encourage youth and adults iteratively and generatively to engage with issues connected to their world and community, with an eye toward designing innovative, equity-centered solutions to real-world problems. Simultaneously, our CS SFL programs support apprenticeship of pre-service teachers and university researchers in the field of first and second language and literacy development. Educators who participate in our programs consistently interact with students to support youth engagement in multimodal projects and to develop their capacity as multicultural participatory teachers and researchers. We see our approach aligned closely to Mirra, Garcia and Morrell (2016) and their inspirational work, as having “implications for re-imagining the nature of teaching and learning in formal and informal educational spaces” (p. 2). The hope is that we can share with readers how and why culturally sustaining SFL practices support the multilingual and civic literacy development of adolescent youth and, at the same time, the development of culturally sustaining pedagogical practices among educators.

Our work draws from social semiotic theories of multimodality, foregrounded first in the seminal work of the New London Group (1996) who framed curriculum as “a design of social purpose” (p. 73). Collier and Rowsell (2014), in a response to this focus on design and multiliteracies, call for its pedagogical applications to include playfulness and allow for “less bounded approaches to literacy that engage bodies, objects, and texts” (p. 25). Our programs encourage youth and adult participants to create and convey their insights to what they identify as significant community assets and problems in their school or neighborhood community. They achieve this through a spectrum of modalities and meaning-making resources (e.g., geographical mapping, drawing, acting and rapping). Simultaneously, the future educators are encouraged to attend to the goals, structure and enactment of curriculum design that is multimodal, participatory, playful and rigorous.

What and Who Are We?

We have been designing and implementing CS SFL programs in our region of the country since 2009. The programs have included a combined teacher education component since 2016. Our work attempts to break out of normative schooling practices and foster a vibrant permeable space with youth fully centered in the work. Over time, our relationships with the youth participants, community members and research team members deepen, although this is certainly not a linear process; we write more about the stops-and-starts of the work later in the book. Still, there are clear successes to point to in the midst of the very real difficulties that come from being in community with others. Indeed, some of our youth participants are now writers in this book or in other projects.

Our programs have involved over 30 doctoral students and an additional 100 graduate and undergraduate students working in participatory ways with youth. The individual contexts and overlapping programs upon which we elaborate throughout the book vary significantly in population, implementation and outcomes. They are, however, tied together by a shared commitment to humanizing frameworks (Paris & Winn, 2013) and CS SFL praxis. We will elaborate more on just what this praxis looks like shortly, but for now it's worth introducing the sites of the work briefly.

CS SFL Programs

Chestnut Middle School

Our oldest program developed through collaboration with teachers and youth at Chestnut Middle School, which had become nearly a predominantly Latine3 school by 2010. When we began our collaboration at the school in 2010 and 2011, anti-immigration policies had made the lives of bilingual immigrant students highly challenging (Harman & Varga-Dobai, 2012). Draconian legislation that led to increased abrupt deportation and a ban on undocumented students from attending public universities was being proposed and passed in state legislatures in the southeast, which triggered huge anxiety among the home communities of students. Our current CS SFL work is embedded in an afterschool program at the school that puts Latine and other youth in conversation with beginning teacher educators enrolled in an initial Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) certification program.

We have used Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) and Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) in a combined framework for thinking about empowering youth and revising the practices and physical space of the school. In the 12-week programs each year, a group of 15 to 18 Latine and African-American youth and 10 to 15 White, Asian and African-American adults are engaged in a range of inquiry modules. The program activities started with storytelling and Photovoice, and then move into mapping, surveying and 3D visual modeling. It culminates with a theater performance. All modules interconnect as they cumulatively develop constructs in urban planning and design.

CS SFL Summer Program

Begun first as a program that was jointly administered by the University College of Education and the school district as a way to fight summer slide and provide dynamic arts education programming for local students, this work has now shifted to our community literacy center. We use a co-researcher model, as with all of our work, putting graduate students in partnership with local youth at two sites: the Georgia Museum of Art and the Parkside Community Literacy Center (PCLC). The aim is threefold: (a) training graduate students in community-based research methods, (b) empowering youth to drive community change through reciprocal relationships with adult co-researchers and (c) providing arts encounters at the museum using spoken word, visual artmaking, performance and freewriting. Adults and youth collaborate in five inquiry modules that culminate in a community performance. The modules that require an increasingly complex and cumulative set of semiotic resources include the following: (a) digital storytelling (taking photographs and sharing stories about their lives in the city); (b) architectural modeling (building ideal and real communities through visual art and blocks); (c) fictional storytelling (reading stories that resonate with youth lives); (d) Boalian (Boal, 1979) theater role-playing and games (enacting lived experiences and discussing with the group) and (e) weekly visits to a museum to “interact” with formal art in a space beyond the school. Through these modalities, each pair of adult and youth co-researchers explore, research and represent what they want to see changed and enhanced in their communities and/or schools (e.g., in 2016, several youth members wanted to see a youth center opened in downtown). Figure 1.1 illustrates this process, showing the community plan designed by one group of youth and adult co-researchers.

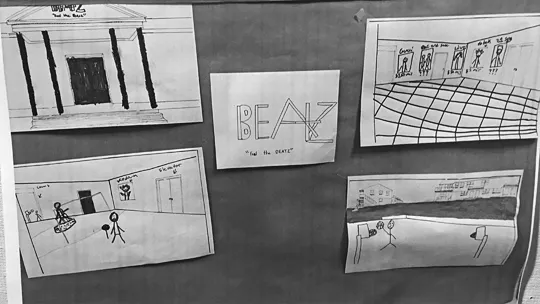

FIGURE 1.1Redesigning Parkside Community Center

The redesigning ideas for the Parkside Community Center in Figure 1.1 highlight how inside play (e.g., the couple playing tennis), the display of youth art and an outside sports space are all part of what the group sees as essential to making the center robust and thriving for residents and visitors to the center.

Yamacraw Action Research Team

In concert with a youth activist writing center in the heart of Savannah, Georgia, we have had the good fortune to train youth writers and artists as community researchers. The work has shifted from teaching youth YPAR methods to a train-the-trainers model, where youth are now training other youth in community research methods. The work also involves identifying systemic issues affecting youth of color in the city, gathering and analyzing field data and creating policy briefs submitted to city and regional officials arguing for reform around the juvenile justice system, poverty, gentrification, food insecurity and media representation of Black and Brown youth.

Parkside Community Literacy Center

Begun as a result of the efforts of a contributing author to this volume, Jason Mizell, and a middle school participant of the CS SFL Summer Program (see Chapter 3 in this volume for details), the PCLC is located in the center of a local federally subsidized housing complex. In partnership with the housing authorities in our city and residents of the housing complex, we have succeeded to some degree—although this is always a humbling project—in creating a small community hub for intergenerational literacy and art programs and community-based research. We have invited undergraduate and graduate students to work side by side with children based on the interests and needs of our youth members. Graduate students with middle school youth have also collected oral histories, coded data and worked with a local muralist to paint a mural of their community design.

University and Medical School Partnership

The Augusta University/University of Georgia Medical School Partnership is part of a two-year community health curriculum for medical students that embeds them in local non-profit organizations with the aim of improving community health as well as developing future medical practitioners who are better oriented to assets and needs in underserved communities. The PCLC serves as a pediatric educational site for beginning medical students who do year-long residencies building community aptitude and relationships alongside their more traditional medical training. In addition, the center serves as a periodic host-site for the medical school's Mobile Medical Clinic; all of this is part of a broader understanding of literacy as holistic and intrinsically linked to community health needs and outcomes.

Who We Are: Our CS SFL Troupe

Because the writing of this book is itself a part of our culturally sustaining SFL praxis, we introduce you here, as much as we can, to our collective authoring voices—they keep expanding—developed through collaborations, struggles and relationship building over the course of roughly a decade. In other words, we do not see this work as developing from a one-person or two-person team but instead from an entanglement of spaces, artifacts, identities and stories that ideally would be represented in the form of an ever-evolving mosaic.

In this section of the chapter, we take time to allow participants in the work—across the spectrum of age and expertise—to introduce themselves and outline some of what drew them to the projects elucidated in the rest of the book. This is vital, we think, because any culturally sustaining work is, of necessity, heavily context-laden, and charged with the stories of its participants, its subjects, its co-authors and loving critics.

Edgar Chagoya

I am a Mexican immigrant from Moroleón, Guanajuato, and a senior at one of the local high schools in our small city. I am a young activist strongly involved in my community. I have participated in a range of CS SFL programs related to civic education and activism, trying to help the voices of the youth community be heard by people who have great influence over their localities, people who can often overlook youths' options, ideas and aspirations. I have received much support from my family, friends and teachers, which has allowed me to open up myself to different opportunities and projects that brought me closer to my community. In the process, I have become more interested in the role our youth gets to take in our community. Since my first experiences I have done my best to continue helping the youth in my community in different ways.