This is a test

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The person-centred approach is one of the most popular, enduring and respected approaches to psychotherapy and counselling. Person-Centred Therapy returns to its original formulations to define it as radically different from other self-oriented therapies.

Keith Tudor and Mike Worrall draw on a wealth of experience as practitioners, a deep knowledge of the approach and its history, and a broad and inclusive awareness of other approaches. This significant contribution to the advancement of person-centred therapy:

- Examines the roots of person-centred thinking in existential, phenomenological and organismic philosophy.

- Locates the approach in the context of other approaches to psychotherapy and counselling.

- Shows how recent research in areas such as neuroscience support the philosophical premises of person-centred therapy.

- Challenges person-centred therapists to examine their practice in the light of the history and philosophical principles of the approach.

Person-Centred Therapy offers new and exciting perspectives on the process and practice of therapy, and will encourage person-centred practitioners to think about their work in deeper and more sophisticated ways.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Person-Centred Therapy by Keith Tudor, Mike Worrall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Philosophy

Philosophy does not initiate interpretations. Its search for a rationalistic scheme is the search for more adequate criticism, and for more adequate justification, of the interpretations which we perforce employ.

Alfred North Whitehead

The attainment of biological knowledge we are seeking is essentially akin to this phenomenon – to the capacity of the organism to become adequate to its environmental conditions.

Kurt Goldstein

One cannot engage in psychotherapy without giving operational evidence of an underlying value orientation and view of human nature. It is definitely preferable, in my estimation, that such underlying views be open and explicit, rather than covert and implicit.

Carl Rogers

To do philosophy is to explore one’s own temperament, and yet at the same time to attempt to discover the truth.

Iris Murdoch

‘Philosophy’ says Howard (2000, p. xiv) ‘underpins therapy as a means to healing, identity, direction and meaning. It deserves more attention.’ We want to begin this book by according philosophy some of that attention. Specifically, we want to look in this chapter at some of the ways in which philosophical principles underpin the practice of therapy, and especially the practice of person-centred therapy.

Before we do that we need to define what we mean by philosophy. ‘Most definitions of philosophy’ says Quinton (1995, p. 666) ‘are fairly controversial, particularly if they aim to to be at all interesting or profound.’ For our purposes we are taking philosophy to mean the underlying principles on which or out of which a person builds a life and chooses how to behave. This is a deliberately limited definition, in keeping with our conviction that the person-centred approach constitutes a functional, rather than an abstract, philosophy.

As we argue in the Introduction, we think that philosophy can help us understand ourselves, others and the world, and that we may ground many of the ideas and much of the practice of person-centred therapy in philosophical ideas. Wittgenstein (1921/2001, pp. 29–30) makes a number of points about philosophy:

- It is not a body of doctrine but an activity.

- It is a meta-activity, and not of the same order of things as the natural sciences.

- It results in the clarification rather than the creation of propositions.

- Its task is to make thoughts clear and to give them sharp boundaries.

We are citing Wittgenstein for a number of reasons. He is one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century, and his work has influenced different schools of philosophy, including logical positivism and analytic philosophy. Some of his later work is compatible with radical hermeneutics and more postmodern perspectives. Although there is no immediate evidence that Rogers read his work, Wittgenstein was pro-foundly concerned with meaning in language and with symbolism, both of which underpin Rogers’ work. Biographically they share a background in empirical sciences – Rogers in scientific agriculture, Wittgenstein in engineering and mathematics – which is reflected in their subsequent fields of psychology and philosophy. Wittgenstein’s view of philosophy as a practice aimed not at solving problems but at resolving them through a better understanding of language supports our current interest in advancing person-centred theory and practice. In his last work (published in 1953, two years after his death) Wittgenstein compares philosophy with therapeutic practice, and a number of writers in the field of therapy have drawn on his work (see, for example, Lynch, 1997; Stige, 1998).

We suggest that the points Wittgenstein makes about philosophy are analogous to the practice of psychotherapy.

- Psychotherapy is not a body of doctrine but an activity. From the beginning Rogers was interested in what worked. He took a pragmatic approach to his work, and grew the theory initially out of his observations and reflections. He saw, too, that descriptive theories could easily become prescriptive and doctrinal, leading to followers arguing about what therapists should or should not do in order to be effective. Writing appreciatively (1959, p. 191) about the way Freud showed ‘more respect for the facts he observed than for the theories he had built’, Rogers saw that ’insecure disciples’ had taken Freud’s ‘gossamer threads’ of theory and made of them ‘iron chains of dogma’. He suggested ‘that every formulation of a theory contains this same risk and that, at the time a theory is constructed, some precautions should be taken to prevent it from becoming dogma’. It’s perhaps inevitable that any activity sustained purposefully over time will generate ideas that some practitioners will begin to hold as doctrine or dogma. ‘Disciples are’ after all, says Phillips (1994, p. 62), ‘the people who haven’t got the joke.’ Wittgenstein and Rogers between them remind us of two things: that the activity comes first; and that, humourless disciples notwithstanding, theory need not, and probably should not, become doctrine.

- Psychotherapy is a meta-activity, and not of the same order of things as the natural sciences. If the natural sciences describe and explore what is, philosophy and psychotherapy are meta-activities in that they offer opportunities to reflect upon the nature of what is. They sit, as Wittgenstein says of philosophy (1921/2001, p. 29), ‘above or below the natural sciences, not beside them’. Clearly, psychotherapy as a process can often do little to change what is. The most effective bereavement therapist cannot bring a client’s mother or lover back to life. Effective therapists can, however, offer their clients a space for them to reflect on what is, and, perhaps more significantly, to reflect on and amend their relationship with what is.

- Psychotherapy results in the clarification rather than the creation of propositions. Wittgenstein (1921/2001, p. 23) describes a proposition as ‘a picture of reality’ and as ‘a model of reality as we imagine it’. Philosophy, then, is primarily about articulating more clearly the propositions that currently are. Given this, we can read his statement as another way of describing congruence. Put into Rogers’ terms, we can say that the process of therapy is not primarily about creating new propositions, or pictures of reality, although new propositions often do emerge. It is, rather, about symbolising and accepting the presence of the propositions we currently live by, and then, by implication, exploring and questioning their validity, accuracy, completeness and usefulness. This clarification, acceptance and examination of our own internal propositions or pictures of reality allows us to experience more clearly and therefore promotes a greater congruence between experience and awareness.

- The task of psychotherapy is to make thoughts clear and to give them sharp boundaries.

This point is implicit in the point above. Its two parts – to make thoughts clear and to give them sharp boundaries - signify two important elements in Rogers’ thinking about psychotherapy. Saying that the task of therapy is to make thoughts clear is another way of saying that its task is to allow clients an opportunity to symbolise their experiences accurately. By this we mean it’s a space within which they may find for themselves the words or other symbols that most accurately and completely describe their internal experiencing. Zimring (1995) suggests that this is exactly what is helpful about therapy. Saying that the task of therapy is to give those thoughts sharp boundaries is another way of describing one aspect of differentiation. Writing about the process of therapy, Rogers suggests that clients move gradually from thinking that is bound by rigid structures to thinking that is increasingly responsive to immediate experiencing, and that is therefore more discriminating of differences between past and present, self and other, fact and construct. One sentence from Rogers catches both of these elements. Writing about one of the seven stages of process (1958/67a, p. 138) he says that clients at this stage tend to show ‘an increased differentiation of feelings, constructs, personal meanings, with some tendency toward seeking exactness of symbolization’.

A further reason for examining philosophical principles is that Rogers sees a significant relationship between private beliefs, or philosophy, and public behaviours, a notion which has immediate roots in Angyal (1941, p. 165):

Any sample of behavior may be regarded as the manifestation of an attitude. Attitudes may be traced back successively to more and more general ones. In so doing one arrives at a limited number of very general attitudes which are unquestionable, axiomatic for a given person. These have been called axioms of behavior. When such axioms are intellectually elaborated we may speak of maxims of behavior. The axioms of behavior form a system of personal axioms. The system of maxims may be called a philosophy of life.

In Angyal’s terms, then, a philosophy of life is a set of intellectually elaborated or articulated attitudes towards oneself and others, attitudes which show in the way we live. Rogers picks up both Angyal’s idea that a person’s behaviour is an outward showing of his philosophy of life, and his process of working back inferentially from observed behaviour to personal philosophy. Doing so he enshrines (1951, p. 19) a therapist’s personal philosophy as an important variable in the process of therapy:

In any psychotherapy, the therapist himself is a highly important part of the human equation. What he does, the attitude he holds, his basic concept of his role, all influence therapy to a marked degree.

Further to this, Rogers suggests (1951, p. 20) that an individual’s personal philosophy of life helps determine the ease and speed with which he becomes a therapist:

Our experience in training counselors would indicate that the basic operational philosophy of the individual (which may or may not resemble his verbalized philosophy) determines, to a considerable extent, the time it will take him to become a skillful counselor.

In other words, a student whose personal philosophy sits easily with the philosophical values of the person-centred approach will become a person-centred therapist more easily and more quickly than one whose philosophy does not.

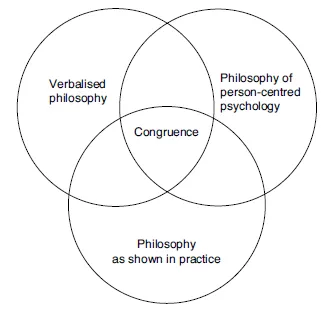

Rogers’ allusion to a possible discrepancy between ‘operational’ and ’verbalized’ philosophy suggests that what we say we believe, or think we believe, or would like to think we believe, may differ from what our behaviour shows about what we believe. This gives us a way of expanding our thinking about congruence. As Rogers formulates it in the context of a theory of therapy (see Chapters 7 and 8), congruence describes a relationship of consistency between a person’s experience, awareness and communication. We expand that definition so that it also describes a relationship between a therapist’s verbalised philosophy and his behaviour; and further between both of those and the philosophical values of the approach to which he subscribes (see Figure 1.1). Swildens articulates (2004, p. 17) ‘one of the fundamentals of psychotherapy as a trade: that there should be a basic connection between a working hypothesis and therapeutic practice’. We suggest that this area of congruence precedes the congruence Rogers believed was necessary for therapeutic work. It is, as it were, a background congruence, out of which or against which emerges the more acute and immediate congruence of a therapist’s experiencing in the moment as she works with her client.

Figure 1.1 Philosophical Congruence

Rogers also asserts that philosophical values, however accurately articulated or intrinsically therapeutic, are not enough in and of themselves. Values are helpful only in so far as they manifest in the lived reality of the relationship between therapist and client. It is, for instance, little use a therapist believing, even genuinely, in the importance of empathic understanding if he has no way of implementing that belief in the moment as he sits with his client. This suggests that effective therapists develop fluid and creative ways of living or implementing their philosophy of life, so that what they believe at the philosophical level becomes a genuine, specific and perceptible way of being in particular lived relationships.

Rogers’ use of philosophical terms

At critical points in his writings Rogers appropriates from the language of philosophy terms which have precise meanings within their original sphere. The phrase ‘necessary and sufficient’ is perhaps the most striking example of this, and suggests that Rogers was at least familiar with philosophical discourse. We think it’s appropriate therefore to examine his work as if it were a philosophy, albeit functional rather than abstract, pure or academic.

Rogers’ theory of therapy (1957, 1959b) depends on what he called the necessary and sufficient conditions of personality change. From his own experience with clients, from the experiences of his colleagues, and from relevant research, he draws out (1957, p. 95) the conditions which seem to him ‘to be necessary to initiate constructive personality change, and which, taken together, appear to be sufficient to inaugurate that process’. His formulation is of an ‘if-then’ variety: ‘if these six conditions exist, and continue over a period of time, this is sufficient. The process of constructive personality change will follow’ (ibid., p. 96). In another paper he asserts that ‘for therapy to occur it is necessary that these conditions exist’ (1959, p. 213). The sense he makes, then, is that the six conditions are both necessary for personal growth, in that they need to occur; and that they are sufficient for personal growth to begin, in that no other conditions need to occur. He uses the words, we think, in their ordinary, everyday senses to describe a causal relation rather than a logical one.

In philosophical discourse, the meaning of the words ‘necessary’ and ’sufficient’, and of the phrase ‘necessary and sufficient’, differs from the meaning those words carry in everyday use, and therefore also from the meaning they have come to have in person-centred thinking, writing and practice. Wittingly or unwittingly Rogers has used terms with a precise meaning in one area to mean something subtly different in his own. This may or may not be a problem. At the very least, however, it offers us another way of looking at Rogers’ formulation.

In philosophical logic necessity and sufficiency are used in two ways. The most common way is to describe logical relationships between propositional variables, as in ‘if p then q’, where p is a necessary condition of the truth of q. The second use, which is the one that we draw on, is to describe two aspects of the relationship between conditions and events. As Hospers has it (1967, p. 293) necessary conditions are ‘conditions in the absence of which the event never occurs’; and sufficient conditions are ‘conditions in the presence of which the event always occurs’. One event (x) is said to be a necessary condition of another ( y) if x always has to occur in order for y to occur. Oxygen is a necessary condition of fire in that a fire cannot happen without it. This is not a causal relationship: oxygen does not cause fire. It’s just that oxygen has to be present in order for there to be fire. Oxygen can, of course, also occur without there being a fire. One event (x) is said to be a sufficient condition of another ( y) if x always occurs in the presence of y. In this formulation, x will never happen without the occurrence of y, although y can occur without x happening. Wind, for instance, is a sufficient condition of a tree’s movement, in that whenever the wind blows, the branches of the tree move. The tree, of course, can move for other reasons, and so wind is not a necessary condition for its movement. To sum up: oxygen is a necessary condition of fire because fire never occurs in its absence; wind is a sufficient condition of a tree’s movement because a tree always moves in its presence. In this formulation, says Hospers (ibid., p. 292), ‘necessary condition and sufficient condition are the reverse of each other’.

Taken individually, the terms ‘necessary’ and ‘sufficient’, then, have both ordinary and specialised meanings. The phrase ‘necessary and sufficient’ has a more exclusively precise meaning within the field of logic, where to describe conditions as ‘necessary and sufficient’ is to say that something happens if and only if those conditions are present: both if those conditions, and only if those conditions are present. This has profound implications for person-centred practice. If Rogers is arguing that the six conditions are, strictly, ‘necessary and sufficient’ then he is saying that therapeutic growth can occur if and only if those conditions are present: that therapeutic change never occurs in their absence, and always occurs in their presence. A statement from the 1959 paper suggests that this is indeed what he meant. He writes (1959b, p. 213) that the process of therapy ‘often commences with only these minimal conditions, and it is hypothesized that it never commences without these conditions being met’. This is a staggering hypothesis. It rules out the possibility of anyone growing or developing or changing through reading a book, or watching a sunset, or hearing a piece of music, or learning to juggle, or watching a film. It rules out the possibility of anyone feeling better on anti-depressants, or after a brush with death that helps her see her current troubles in a different perspective. It also asserts that therapeutic change will, always and inevitably, follow the six conditions. Given that Rogers developed an approach to therapy that values fluidity, responsiveness and a tentative attitude to experience, we think it’s ironic that he should have couched his thinking at this point in such absolute, all or nothing terms.

We’ll suggest later when we look at the history of each of the six conditions in more detail that Rogers may have been moving away from this position towards the end of his life. Subsequent theorists too have questioned the necessity and sufficiency of the conditions, particularly in the light of the part clients themselves play in effective therapy. Rodgers, for instance (2003), reviews some of the qualitative studies of clients’ experiences, and suggests (p. 20) that ‘it is the client’s involvement in therapy that is found to be of key importance’. Bohart (2004) agrees that most descriptions of the process of therapy are (p. 103) ‘therapist-centric’ in that they privilege the therapist’s intentions and behaviour, and discount or minimise the role the client himself plays in his own therapy. There is also, Bohart says (p. 106), ‘evidence that many individuals with problems recover or solve them without our help as all-seeing benevolent therapists’. Schmid (2004, p. 49) echoes this. ‘Therapy’ he says ‘is more than a matter of therapist variables; it is a matter of the client’s self-healing capacities.’ Moreover, in perhaps the most extensive piece of research conducted into person-centred therapy, in this case with schizophrenics (Rogers et al., 1967), the report concludes (Kiesler, Mathieu & Klein, 1967, p. 310): ‘that the results of this study have not been interpreted as supporting our theoretical specifications of a causal relationship between therapist conditions and patient process movement’ (our emphasis). Instead, they conclude that patient factors and therapist attitudes create a mutually interactive process and thus (p. 309) ‘it seems most appropriate to conceive of therapy outcome as a complex function of their dynamic interaction’.

What do we get if we look at the six conditions through this framework? We argue that the six conditions prove to be neither necessary nor sufficient, in this strict, philosophical sense of the words.

Look at necessity first. We agree that the conditions are intrinsically helpful and often implicated in therapeutic growth. The question, though, is whether they must necessarily be present in order for growth to occur. Put another way, can therapeutic growth ever occur independently of the six conditions? Our experience is that it can and does. People do make therapeutic changes on their own, in the gym, walking on a mountain, reading a book or listening to music. The changes may have roots in moments of relationship. A person’s perceived or subceived experience of being understood and accepted may precipitate therapeutic change. But often the moments of change themselves take place in solitude, out of any psychological contact with another human being, and therefore out of any immediate experiencing of empathic understanding or unconditional positive regard.

If the conditions are sufficient for therapeutic change, then therapeutic change happens inevitably in their presence. Barrett-Lennard (2002, p. 146) q...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Advancing Theory in Therapy

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Series preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Philosophy

- Chapter 2 Organism

- Chapter 3 Tendencies

- Chapter 4 Self

- Chapter 5 Person

- Chapter 6 Alienation

- Chapter 7 Conditions

- Chapter 8 Process

- Chapter 9 Environment

- Appendix 1 References for Epigrams

- Appendix 2 Philosophical contributions to the understanding of self

- Appendix 3 A process conception of development and psychotherapy

- References