1: The return of the repressed? British horror’s heritage and future

Steve Chibnall and Julian Petley

It is now nearly thirty years since David Pirie published his seminal A Heritage of Horror, and far too many since it was last in print. In the intervening period there has been an explosion of interest in the Gothic in general, and in horror cinema, Gothic or otherwise, in particular. Whereas the unfortunate Pirie had little more to draw on for critical sustenance than works such as Mario Praz’s The Romantic Agony (1933), Devendra P. Varma’s The Gothic Flame (1957) and the journal Midi-Minuit Fantastique – all of them admittedly formidable in their different ways – the modern enthusiast for horror in all its forms has a truly remarkable number of texts to consult, as our contributors’ bulging references amply testify.

However, in the case of texts on British horror cinema, too many fail to progress beyond considering what has become a pretty limited canon. In this respect, Jonathan Rigby’s recent English Gothic: A Century of Horror Cinema deserves particular welcome for bringing such a wide range of films within its ambit, as does the ten-part survey of British horror in the 1970s and 1980s carried out by the magazine Flesh and Blood. Indeed, the appearance in recent years of genre magazines written by enthusiasts for enthusiasts has been one of the most welcome developments on the horror scene, helping to create a valuable sense of community among horror fans in hostile times, allowing new writers on horror to emerge and develop, and drawing attention to neglected films and directors. Magazines such as Little Shoppe of Horrors, Dark Terrors and Hammer Horror have also performed an invaluable service in minutely excavating the archaeology of Britain’s most prolific supplier of fantasy films, Hammer studios. In fact the diligent burrowings of the researchers associated with these Hammer fanzines, together with academic work on the studio and its leading director by Peter Hutchings (1993 and 2001) and Wheeler Winston Dixon (1991), have cleared a space for this book to explore more neglected areas of Britain’s horror film heritage. In doing so, we hope to embed the fanzines’ empirical findings on production histories more securely in the generic and reception contexts of the films.

In bringing together the various contributors to this book we were certainly motivated by the desire to draw attention to films and figures outside the canon, movies and people who have still not significantly benefited from the recent upsurge of interest in British horror cinema. To extend a metaphor first used by one of us a decade-and-a-half ago, now that the ‘Lost Continent’ of British fantasy cinema has been rediscovered, we want to continue its cartography beyond the landing zone. Hence, for example, Peter Hutchings’s chapter on Amicus (dealt with fairly briefly by Pirie, but recently celebrated by Alan Bryce’s Amicus: The Studio That Dripped Blood (2000), a book emanating from another fanzine, The Dark Side), which also very usefully suggests that, as well as locating their films within British culture at the time of their production, we also need to look at the American influences at work on them. Similarly, Ian Conrich delves further into the past than Pirie to resurrect such largely forgotten early British horrors as Castle Sinister (1932), The Ghoul (1933) and The Face at the Window (1939), while Marcelle Perks contributes the most substantial study to date of the woefully neglected Death Line (1972) and Steve Chibnall explores the work of a post-Hammer ‘auteur’, Pete Walker, who, for a moment in the mid-1970s, suggested new possibilities for Gothic cinema in Britain. By taking a thematic approach, as opposed to one centred on a particular auteur or company, Leon Hunt, Kim Newman and Steven Jay Schneider are able to tackle an extremely wide range of films, many of which have barely received serious consideration before, and to isolate recurring motifs and patterns which suggest the deep cultural strains and tensions into which these films were tapping. Many of the films they discuss are original screenplays, but we are also mindful that one of the distinctive features of the horror films produced in Britain is their strong links to a tradition of fantasy literature, and these connections are foregrounded in John C. Tibbetts’s close examination of the adaptation for the cinema of Henry James’s novella, The Turn of the Screw.

Figure 1 Hammer and sickle: Peter Cushing does some vampire hunting in Twins of Evil (1971), one of the Hammer studio’s classic Gothic tales.

This book, however, is about not simply British horror films but British horror cinema. In other words, it is concerned not simply with films as texts but with the institutions and discourses within which those texts are produced, circulated, regulated and consumed, and the book begins with three contextualizing chapters. Almost inevitably, given the amount of cutting and banning with which horror films have always had to contend in Britain, the first chapter is on censorship. Mark Kermode examines how the British Board of Film Censors/Classification has dealt with British horror films by placing this in the wider context of the Board’s treatment of horror films in general. Especially valuable are his close textual readings of passages from former censor John Trevelyan’s book What the Censor Saw, which expose many of the unspoken assumptions and attitudes underlying the censorship of the moving image in Britain. That these are extremely deep-rooted within the British cultural establishment, of which the mainstream critics make up a key cadre, is demonstrated in Julian Petley’s chapter on critical attitudes towards horror, which also suggests that, in certain respects, these attitudes have significantly hampered the development of horror cinema in Britain in recent times. The paranoia which censorship and critical denigration of the genre have fostered in many horror fans is amply illustrated by some of the remarks cited by Brigid Cherry in her study of female horror film enthusiasts. However, Cherry’s main focus is the role played by horror cinema (particularly vampire films) in the lifestyle of a range of women. Her work represents an important corrective to the easy gendering of the genre’s audience (and, by extension, the genre itself) as male, and offers valuable insights into the way female enthusiasts actually relate to the films they watch – as well as to other fans.

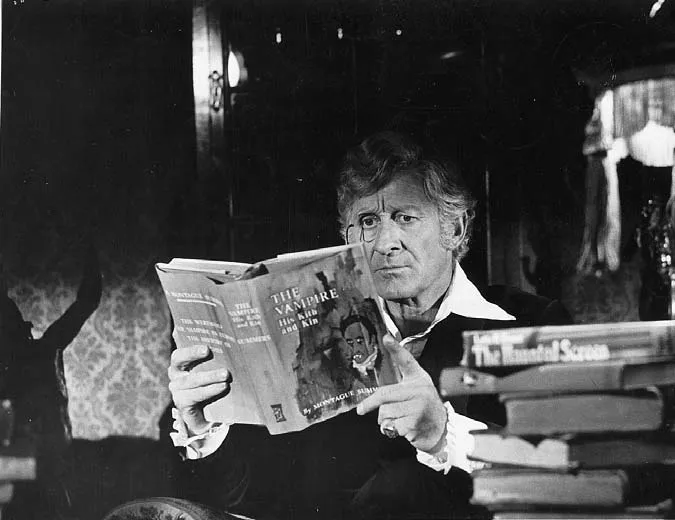

Figure 2 Literary heritage: Jon Pertwee catches up on some bedtime reading in Amicus’s The House that Dripped Blood (1970).

The last two chapters of this book attempt to bring up to date the story of the horror film in Britain. Paul Wells looks at the work of one of Britain’s recent undoubted horror auteurs, Clive Barker, and, in his interview, Barker’s highly articulate discussion of the genre and of his own work within it makes for a remarkable – not to say welcome and refreshing – contrast with the journeyman attitude of many of its past practitioners.1 The same is true of the account of recent horror by Richard Stanley, who was responsible for Hardware (1990) and Dust Devil (1993), two of the last decade’s most striking British entrants in the horror, or horror-related, stakes. Stanley’s chapter mentions numerous British horror movies of the 1990s, but does so in a distinctly valedictory spirit, and this prompts us to conclude this introduction by reviewing the various reasons put forward for the decline of the British horror film, and by enquiring if this decline is in fact more apparent than real.

In 1973, David Pirie, in his chapter ‘Towards a new horror mythology’, admitted that ‘the Hammer horror movie at its most traditional has inevitably suffered from an increasing public sophistication.… It is no longer possible to make naive straightforward English horror films that are as simple in narrative but as rich in connotation and suggestion as Hammer’s early efforts’ (165, 167). He also complained, with the ‘Karnstein’ films The Vampire Lovers (1970), Lust for a Vampire (1971) and Twins of Evil (1971) clearly in mind, that:

The dark, over-laden allusiveness [of traditional Hammer] is being replaced more and more by banal sexual antics, the charged hermetic atmosphere by heavy-handed humour, the solid narrative structure by half-understood experimentation. At times the new English films even begin to look like bad imitations of the European horror films, for many of the younger British filmmakers have begun to ape the overtly Freudian and surrealist intellectual quality of the French approach to horror, without understanding the essential historical value of their own tradition.

(ibid.: 165)

Pirie rightly perceived the just-deceased Michael Reeves, as

the kind of film-maker which the British cinema needed (and still needs) so desperately badly: someone who could merge the popular tradition of horror film with more avant-garde concerns without rearing the curious bastard which so often results from such experiments.

Furthermore, he contended that Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968)

contains the seeds of something which could yet develop into an important cinematic idiom in this country, and one which is as intrinsically native to England as the western is to America. The literary romantic tradition into which it shades has as much affinity with Malory as with the Gothic and is virtually untapped by current popular English forms.

(155)

Unfortunately this remains as true today as when it was written. The films based on Walpole, Radcliffe, Maturin, Lewis and other Gothic writers, which Pirie hoped to see, are still unmade, and when Pirie himself became a script writer, it was to television that he had to turn to commission his adaptations of Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White (1996) and Sheridan Le Fanu’s The Wyvern Mystery (1999), as well as his Gothic-tinged original scripts Rainy Day Women (1984) and Murder Rooms (1999). In this respect it is extremely significant that Jonathan Rigby (2000) quotes Stephen Volk, the screenwriter of Ken Russell’s Gothic (1986) to the effect that:

In this country, the film establishment is so intellectually pompous that they wouldn’t admit to watching Gothic horror, let alone commissioning it. It’s one of the very few cultural exclusives that we could really exploit … but it’s so hard to get anybody interested.

(244)

Only very briefly, in a trio of films by Pete Walker, was Pirie’s hope realized that British horror cinema might be able to follow the American example of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) and ‘combine the best and most traditional elements of the old approach with more complex ideas and emphases’ (ibid.: 167).2 Various authors have suggested that it was precisely the British horror film’s inability to keep up with modern developments in the genre which led to its alleged demise. Thus, for example, Kim Newman (1988) argues that: ‘The British horror film perished because of its inability to adapt to a 1970s world beyond Home Counties Transylvania’ (25), while David Sanjek (1994) similarly contends that audiences faced with the rapid and often disquieting transformations which British society was undergoing in the late 1960s and early 1970s no longer responded to the ‘artificial horrors’ of the Hammer school. Instead, he argued, ‘to remain worthy of attention, the British horror film would have to embrace the monstrous in [the] audience’, adding that, ‘few horror films produced in England between 1968 and 1975 achieved this goal’ (197).

Elsewhere, Ian Conrich has argued that: ‘The British horror film in its generic form has become fragmented since the early 80s. The absence of any British film studios or recognised producers of horror – a Hammer, Tigon, Tyburn – has created a weakened generic image’ (1998: 27). In order to illustrate his thesis, he takes the example of Palace, which, between 1984 and 1992, produced five horror-related titles: The Company of Wolves (1984), Dream Demon (1988), High Spirits (1988), Hardware (1990) and Dust Devil (1993), and concentrates on how these were marketed. What Conrich’s article shows is that The Company of Wolves was successful at least in part because it was well marketed, both to a horror audience but also, more importantly, as an ‘art house’ product via the Angela Carter connection. It was also a critical success. Dream Demon, however, pleased neither the critics nor the ‘arty’ types, and horror fans found it merely derivative of the Nightmare on Elm Street films. Finally, in what seems like an act of desperation, it was sold on the attractions of Timothy Spall and Jimmy Nail! Then, when Hardware came along, it was sold, at first at least, purely as if it were an American film, ‘the Terminator for the Nineties’ as The Face put it. Conrich quotes Daniel Battsek of Palace as stating that ‘there is no point from a marketing point of view in selling a horror film as British, at least not in the beginning’ (ibid.: 30). This is a bitterly ironic state of affairs for films in one of the only genres Britain can claim as its own. The difficulties which home-grown horror has faced in the market place from the 1970s onwards (not least from the consequences of intense American competition) are clearly evident in Richard Stanley’s chapter in the present book. As Stanley makes all too plain, Palace’s valuable if limited contribution to the horror genre was finally terminated by the collapse of the entire company. In such circumstances it may not be entirely surprising that, as Jonathan Rigby argues, ‘1990s British horror films seemed content merely to replicate other people’s horror films, and their models tended to be American ones’ (op. cit.: 244).

Palace’s problems and ultimate collapse suggest that we cannot look at the state of the horror film in Britain from the 1970s onwards in isolation from the condition of British cinema as a whole during this period. The fact of the matter is that, for much of this time, the indigenous production sector has been in a state of crisis that at times has seemed almost terminal. Thus, for example, in 1971 a mere 67 films of any kind were made in Britain, and in 1982 the figure had dropped to 46. It is true that, in the early 1970s, by offering a haven for low-budget film-making, the horror genre suffered less than others from the withdrawal of American capital from British film production.3 By the end of the decade, however, even the most modest of productions were finding it impossible to recoup their costs in their home market, as more cinemas closed and audiences dwindled. During the 1980s the general plight of British film production improved somewhat thanks to the financial input of bodies like Channel 4 and British Screen, but their money was not directed at popular genre cinema. This has had to await National Lottery funding, but so far the main result of this largesse has been a revival of the crime, not the horror, film.

Figure 3 The attractions of Timothy Spall (right) and Jimmy Nail: Palace’s Dream Demon (1988).

The reason for this may be quite simply...