Chapter 1

Who is research for?

Mike Slade and Stefan Priebe

Introduction

This book has the aim of positioning methods of mental health service research in a wider context, by considering the potential and actual impact of evidence from different methods on a range of target audiences. There is clearly a need to use a variety of methodologies: to address the different types of research questions, to explore and answer the same question in a number of ways, to ensure that proportionate effort and resources are applied, and so forth. However, different research methods produce different types of evidence, and each type of evidence may have distinct levels of credibility with each audience of research consumers.

Research has a purpose in society, although this may often be forgotten in the everyday work in research. The purpose is to produce evidence that will help to improve mental health care and, hence, the lives of many people with mental health problems. The relationship between research production and research consumption is likely to be complex, and will be analysed in this book. This will be done from different angles, with the aim of providing a comprehensive picture.

The impact of research may be mediated through the evidence that the research provides. Yet, there are different concepts of evidence. For example, postmodern epistemology (among others) would challenge the assertion that evidence exists as an absolute concept, irrespective of the context, type of question, and the person or group using the evidence. Rather, evidence may be better seen as meaning ‘explanation’, with each type of evidence varying in its social force on the basis of what it is used for and who is using it. In other words, the impact of research does not depend only on the inherent qualities of research, but also on the willingness and ability of audiences to take notice of and accept different types of evidence, and on factors influencing the relationship between research production and its impact in the real world. Considering this relationship may help in research planning and commissioning.

Traditional model of research

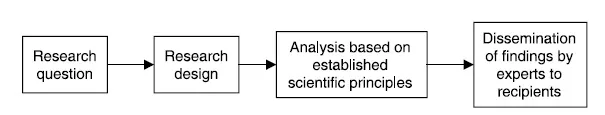

The traditional model of health service research is shown in Figure 1.1. This model places the initial stages of research and the selection of methods in a kind of vacuum, and changes currently occurring in society raise challenges for this model. Recent events in the UK illustrate these changes. An article in the Lancet in February 1998 suggested a link between the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism (Wakefield et al, 1998). What happened next starkly demonstrates some of the societal changes – in relation to knowledge, trust, risk and choice – which are taking place.

- The hierarchy of evidence employed by the public differs from that employed in evidence-based medicine (Faulkner & Thomas, 2002). The Lancet study involved 12 children (Wakefield et al, 1998). Within an evidence-based medicine approach, a case series has limited value in establishing a causal relationship, and is the wrong scientific method for confirming a causal relationship between relatively common events. As a method, it ranks very low on the hierarchy of evidence used in evidence-based medicine (Geddes & Harrison, 1997). For the public, by contrast, it is plausible that the small numbers increased the salience. Certainly, most members of the public were unfamiliar with the Finnish study of 1.8 million children (Peltola et al, 1998) or the Danish study of 537,000 children (Madsen et al, 2002), which, along with all other scientifically robust studies, refuted any connection between the vaccine and autism.

- The expert may be less trusted by society. Numerous clinical academics and researchers gave press and media briefings to inform concerned parents about the safety of the vaccine. Despite these reassurances, take-up rates fell from 91% in 1998 to 79% in 2003. Latest published figures (the year to March 2004) show the uptake rate stabilising at 80%. The subsequent uncovering of an undisclosed financial interest by the first author of the original study (reported online by the Lancet on 23 February 2004) increased this process of public disenfranchisement from scientific expertise. This indicates that medical doctors may be less trusted by the public, although research on the subject still shows a high level of trust in them.

- There is an increased preoccupation with risk (Beck, 1986). A central theme in the debate was the concept of ‘risk’. For the scientists, risk was used in the sense of potential danger. By this definition, risk is unavoidable, and the goal is to balance different types of risk (i.e. the risk of developing autism following the vaccination and the risk of developing any of the conditions being vaccinated against). For concerned parents, risk was being used in the sense of actual danger. By this definition, any risk is unacceptable, and the goal is to avoid risk. The societal preoccupation with risk in the UK since the late 1990s, and the difference in meaning between scientific and non-scientific audiences, came into focus when experts proved unwilling to state categorically that the vaccine did not cause autism.

Figure 1.1 Traditional model of scientific enquiry.

- There has been a rise of consumerism, choice and empowerment (Muir Gray, 1999). Individuals are encouraged to choose what sort of health care to access and use. This has led to the development of the ‘informed patient’, who is given the best available information and then supported by the clinician in deciding what health-care interventions (if any) to opt for. The MMR debate illustrates how the assumption that giving parents information would lead them to make the ‘right’ (i.e. scientifically indicated) decision about vaccinations proved false. As noted, the vaccination rate fell to well below the 95% rate recommended by the World Health Organisation for ‘herd immunity’. Consequently, there were 467 confirmed cases of mumps in April to June 2003 in England, compared with 84 for the same period in 2002. Similarly, measles incidence rose for the same period from 52 in 2002 to 145 in 2003. The public health implications of moving from decision making by experts to decision making by individuals are both profound and unexplored.

These changes are consistent with postmodernist concepts, and have implications for mental health service research.

The position of mental health care

Psychiatry has a chequered past. Modern psychiatry was established as a medical profession with the rise of the Enlightenment approximately two centuries ago, and since then has been characterised by specific tensions that have not been shared – or at least not to the same extent – by other medical specialties. One specific issue has been the long struggle of psychiatrists to be part of conventional medicine, having the same prestige, status, income and power as other medical doctors. Another issue has been the balance between therapeutic aspiration and social control, psychiatry being the only medical specialty that treats a significant proportion of patients against their will. Other aspects make psychiatry unique within medicine. Psychiatry has been misused as an instrument of state control and political oppression. These cases may have been rare, but may nevertheless have tainted the reputation of psychiatry. Historical examples include the ‘sluggishly progressing schizophrenia’ diagnosis given to Soviet political dissidents, and – less publicised – the recent role of psychiatry in China in relation to the Falun Gong sect (Stone, 2002). More widely, the very concept of mental illness has been challenged (Szasz, 1961), in a way not found in other branches of medicine (Bracken & Thomas, 2001).

Psychiatry survived the antipsychiatry assault in the 1960s. Perhaps it is now sufficiently developed as a discipline to embrace rather than withstand the concerns of ‘post-psychiatry’ (Bracken & Thomas, 2001). One important element of this response concerns research – the lifeblood of any respectable scientific profession. Here, too, traditional practice has been criticised. A gap exists between professional and service user priorities for research (Thornicroft et al, 2002), and there is a call for user-led mental health service research (Faulkner & Thomas, 2002). We therefore turn now to the role of mental health service research in the modern world.

Mental health service research

The era of the trusted expert, who uses the best available research evidence to inform advice to ideally passive patients, might have passed. Individuals can now much more readily access and use a range of information – some ‘scientific’, some not – to inform their health behaviours. Even when scientific evidence is present in the information ‘market place’, the MMR debate highlights that the media and the public may interpret research evidence in different ways from that planned by researchers.

One possible response from the scientific establishment to this analysis of social changes is to do nothing. This risks scientific evidence becoming increasingly marginalised and subjected to spin in important health-related debates.

A second possible response, which is becomingly increasingly common, is to embark on a public education approach. The aim is to explain more clearly the strengths and limitations of research evidence to non-scientifically trained members of the population. The success of this approach has not been formally evaluated, but is based on the assumption that society, having ‘moved’ in the ways outlined earlier, can be persuaded to move back. On the basis of the available anecdotal evidence (e.g. from the MMR debate), we are unconvinced that this assumption is correct.

A third option is that well-worn phrase, a ‘paradigm shift’ (Kuhn, 1962), and this is what we argue for. Specifically, we suggest that research planning and research production should not take place in isolation without considering research consumption. Rather, the intended target audience for a research study should inform the design of the study – including the choice of method – and the dissemination and presentation of the findings. To put this from the perspective of research commissioners, the likely impact of a study can be used as a relevant criterion for evaluating the quality of a research proposal. ‘Applied’ research which is more likely to affect the target audience should be prioritised over ‘applied’ research which is less likely to have an impact. We need to develop methods for differentiating between the two.

The book explores the implications of this suggestion.

Goals of the book

Previous books on research methods in mental health have focused on the link between research question and research design (e.g. Prince et al, 2003; Parry & Watts, 2004). This book, by contrast, investigates the link between research design, the intended target audience and the potential impact. We seek to focus attention more explicitly on the type of audience which the researcher is seeking to influence, the types of evidence which each audience accepts as valid and relevant, and the relative strengths and limitations of different scientific methods for providing different types of evidence.

The book has the following four goals:

- to present the perspectives of a wide range of academic disciplines on mental health service research

- to provide a learning resource for students and more experienced mental health service researchers to broaden their conceptual and technical knowledge

- to develop a sophisticated understanding of the relative merits of different research designs

- to inform the selection of the best research method, with due consideration paid to the intended audience for the research.

Structure of the book

The book has three parts. Part I reviews a wide range of methods. Each chapter provides a brief outline of the methodology, providing pointers to more detailed texts for the interested reader. The link with other methods is then explored, by elaborating their embedded assumptions. The types of evidence which is produced by the methodology are then discussed, leading to consideration of what research questions the approach is most applicable to. The existing contribution of the methodology to mental health research is then reviewed, illustrated by a case study. Finally, future potential for the approach is considered. Each chapter follows the same structure, so that the reader can compare potentials and limitations, strengths and weaknesses of the different methods. The order of chapters progresses from investigation of individuals to research at a population level. The methodologies chosen for inclusion are not exhaustive – omissions include non-randomised designs, anthropological designs and consensus techniques. The included methodologies were selected to illustrate the range of research in mental health. Part I is intended to provide a set of connections within and between methods, so that the reader can judge the current and potential level of importance attributed to the approach.

Part II investigates the use of research to change behaviour or practice. Contributors to this section are representative of, or expert in influencing, different target audiences. Each chapter begins by describing the types of evidence that have high salience for the specific audience, illustrating with a case study. Non-scientific evidence that is influential for the target group is then identified. It is said that history repeats itself, possibly because nobody listens. Each chapter therefore concludes with a case study of research which has not had the intended impact, with the aim of informing future research design. Influencing policy is a particularly important issue, and so separate chapters are devoted to experiences in the UK, Germany, Italy, Sweden and the USA.

Part III moves from description to intervention. We seek to synthesise the observations made about research production in Part I and research consumption in Part II. Consistent with its philosophical underpinnings, we do not seek in this book to make universally valid recommendations – the book is structured to open up questions, rather than prescribe action. The concept of evidence is considered in Part III from sociological, mental health service user, and postmodern perspectives. We end by outlining an emergent conceptual framework for mental health service research.

Using the book

Some guidance for the reader who wishes to dip in may be helpful.

For the postgraduate (or ambitious undergraduate) needing to select a research method for a thesis, Part I provides a rich description of the relative merits and issues with a wide range of methods. Similarly, critical appraisal skills will be enhanced by learning more about when (rather than just how) to use the different methodologies.

For the clinical reader looking for a summary of the ideas (in order, perhaps, to state authoritatively at a clinical team meeting, ‘The evidence clearly shows . . .’), Part III summarises the key emergent themes.

For research commissioners, the central message of this book is that the type of research to commission is a function not just of the research question but also of the target audience. The chapters in Part II may help clarify thinking about the intended target audience. Researchers need assistance to do things differently. Part III may help commissioners to guide the research community toward developing high-impact (and not just high-quality) proposals.

And, finally, for mental health service researchers, such as ourselves, Parts I and II may provide a different perspective on scientific ‘quality’, by considering impact as well as scientific rigour. It will be a challenge to change practice, and Part III is intended to give practical pointers for action.

Figure 1.1 Traditional model of scientific enquiry.

Figure 1.1 Traditional model of scientific enquiry.