eBook - ePub

Psychodrama Since Moreno

Innovations in Theory and Practice

This is a test

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychodrama Since Moreno

Innovations in Theory and Practice

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Internationally recognised practitioners of the psychodramatic method discuss the theory and practice of psychodrama since Moreno's death. Key concepts of group psychotherapy are explained and their development illustrated.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Psychodrama Since Moreno by Dr Paul Holmes, Paul Holmes, Marcia Karp, Michael Watson, Dr Paul Holmes, Paul Holmes, Marcia Karp, Michael Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Encounter as the principle of change

Commentary

The first three chapters demonstrate the clinical excitement and therapeutic power of psychodrama to create change and reflect on how the method entails more than the sum of its parts.

In the first chapter Ken Sprague takes the reader right to the heart of psychodrama through the discussion of the central tenets of Moreno’s philosophy: time, space, reality and cosmos. These concepts challenge the reductionist model of some other psychotherapies (which see the cause of human distress as lying within the individual) and establish psychodrama’s difference, and indeed potential for alienation, from the scientific, medical model, that underpins psychoanalysis and psychiatry.

In the second chapter, Marcia Karp takes two of the cornerstones of Moreno’s theories, creativity and spontaneity (which together he believed to be the greatest of human resources), and shows passionately how they can inform the work of the psychodramatist. She gives examples of some of the ways the therapist can transform a group’s experience of itself. Reflecting both the authenticity and inspirational qualities of psychodrama, she guides the reader through moving accounts demonstrating how an appreciation and application of these concepts can transform a situation towards both problem solving and health.

In the third chapter Dalmiro Bustos considers and develops Moreno’s ideas on the locus, matrix and status nascendi. These concepts refer to the place and time at which something originates and its final form. Their use in clinical practice allows for links to be made between the source of emotional problems and the methods that may bring about change. Some psychodramatists are perhaps not fully conversant with the potential of these ideas; they are, however, central to Moreno’s metapsychology.

Moreno was a charismatic figure and there is a clear line of inheritance among the generation of directors trained by him. Two of the authors in this section, Dalmiro Bustos and Marcia Karp, worked with Moreno at Beacon. Each of these chapters has a directness which we hope will excite and instruct readers, both those who are new to psychodrama and those who are familiar with the method.

Chapter 1

Time, space, reality and the cosmos The four universals of Moreno’s philosophy

Commentary

The long tradition of folk tales that make sense of the world and hold a culture together find expression in our first chapter in which Ken Sprague breaks with academic tradition and uses his own creative technique of story-telling to introduce us to psychodrama and to the four fundamentals of Moreno’s philosophy: time, space, reality and the cosmos.

Stepping into the cosmos with our feet on the ground

Imagination is more important than knowledge.

(Einstein 1932, quotation on poster of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

I am fascinated by the connection of psychodrama, books and storytelling. For me, every session opens an illustrated book of the protagonist’s life.

Page after page, past, present and future of a group member’s experience and dreams are re-created before our eyes. Things that didn’t happen and perhaps should have happened are given life at last. Psychodrama is about what didn’t happen as well as what did.

It all takes place in the time slot of the here and now. The group’s energy flows to the stage in support of the protagonist. Each member waits, willingly available to be an auxiliary if called upon. The seeds of change are sown.

Stories and pictures have always caught my imagination. My hardearned wages as a 13-year-old baker boy were spent within minutes of payment. I ran all the way to an antiquarian bookshop to buy bound but battered Saturday magazines. On one wondrous occasion the kindly bookseller let me have an Arabian Nights, The Thousand and One Tales printed in 1835, price threepence.

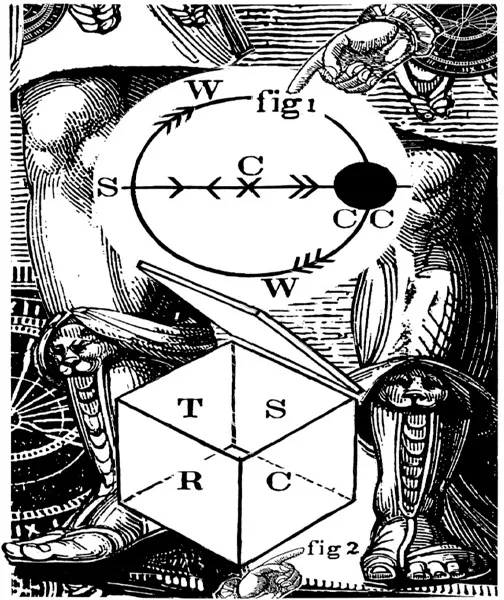

Before buying, I insisted the books be illustrated with black-and-white wood engravings. These were often crude apprentice work owing more to travellers’ tales and the imagination of the artists than to their actual knowledge. (Some of these engravings are the basis of the montage illustrations in this book.)

Imagine my delight when, years later, Danny Yashinsky of the Toronto School of Story-telling gave me the following quotation:

Besides the drama the thing that influenced me most was the tales of A Thousand and One Nights. To be perfectly honest with you, I really owe it to those Tales and to the tremendous world of Persia and how roles were played then on the reality level in the streets of Baghdad and how it was told to us in such a wonderful fashion. And so if you want to become a role-player you ought to read that book again.

It contains all we want to tell you tonight.

(Moreno 1948, unpublished transcript of a psychodrama session in New York City)

Because of the importance of all this to me, this personal view of Moreno’s philosophy is presented with stories and with comments. I want to tell what, for me, psychodrama’s underlying philosophy is about, to show how it can be enjoyed and to suggest ways of discovering its relevance for us all as we approach the twenty-first century.

First story

Dr Moreno was walking on Columbus Circle in New York City. A policeman and a black man were having an argument. Moreno entered the situation and said, ‘Excuse me, I’m a psychiatrist. Can I help?’ Whereupon the two were each asked their side of the story. It ended with the black man being allowed to go on his way.

(Z.Moreno 1993, personal communication)

Moreno didn’t pass by on the other side of the street thinking it was none of his business. He didn’t dismiss the event as a case of a policeman doing his job. He didn’t ease his conscience with the idea that the black man was, in all probability, a villain deserving retribution. He went over and got involved. He poked his nose in. Most importantly he took his professionalism beyond his doctor’s office to show that psychodrama belongs in the street as well as in the clinic. The ongoing problem is that often we leave our skills in the therapy room and meanwhile the world proceeds to go horribly mad! James Hillman looks at it from another angle:

Every time we try to deal with our outrage over the freeway, our misery over the office and the lighting and the crappy furniture, the crime in the streets, whatever—every time we try to deal with that by going to therapy with our rage and fear, we’re depriving the political world of something.

(Hillman 1992:5)

Surely Moreno anticipated this dilemma when he designed psychodrama as a life tool not just something for use in the clinic. He makes it explicit when he asks us to see ourselves operating responsibly in three dimensions —the personal, the social and the cosmic. There’s nothing mystical about it, he’s simply saying, keep our feet fair and square upon the ground, attempting to solve its problems even as we reach for the stars: it’s all connected.

Second story

My partner, Marcia Karp (who was trained by Moreno), and myself attended the Eleventh International Congress of Group Psychotherapy in Montreal. On the second day we were walking in the Congress Plaza. It was early evening with a grey sky and a hint of rain to come.

Two elderly Chinese were doing Tai-chi, their movements emphasising the emptiness of the ugly concrete complex and its surrounding space. A young woman entered from the far corner of the Plaza and walked, head down, towards us. We had seen her in the Congress Hall earlier and knew that she was from one of the East European delegations. She caught sight of us, hesitated for a moment, and then veered away. Clearly something was wrong.

Marcia and I had been enjoying being together after a hectic day of plenary sessions, workshops and crowded meetings with friends old and new—the stuff of international congresses.

Marcia let go of my hand, went straight up to the young woman and said quietly, ‘You look tearful; would you like a hug?’ The two women held each other while the younger one cried. After a while she raised her head, looking somewhat embarrassed. Marcia said quickly, ‘May I double you?’ There was a grateful nod and Marcia stood alongside the young woman, adopted the same slightly stooped position, the same embarrassed expression and said, ‘I can’t stand being treated like a pauper. Nobody understands how I feel.’

The young woman gestured with her hand in a secretive behind-the-back movement and said, ‘Yes, they are putting money in my hands as if it’s a dark secret. I don’t want their dollars.’

Marcia (as the double) said, ‘I feel terrible. They make me feel cheap. How can I tell them that inside I feel richer than they are.’

‘Yes, yes. How can I tell them of the richness of my own culture?’ replied the young woman with energy.

We then heard the tale of coming from Eastern Europe (in itself no small task at that time) into the unhuman scale of the Palais de Congrès and opulence of the hotels used by the delegates. We heard of misunderstandings about money and of thinking that the expensive Congress fee (enormous by eastern European standards) included accommodation. Instead there were fees for everything: fees for breakfast and fees for coffee; fees for lunch, dinner, and for taxis to and from the proceedings. Our new friend had hardly eaten since arriving in Montreal.

All this at a congress entitled, ‘Love and Hate—Toward Resolving Conflict in Groups, Families and Nations’.

Dr Moreno in New York and Marcia Karp in Montreal took the simple and direct action of poking their noses in.

There are three things that strike me about their two encounters:

HOW they did it. This I would call technique and personal style: both are important in psychodrama.

WHY they did it. This could be called theory—an understanding of which is essential for all practising the method.

THAT they did it. This I would call philosophy.

The philosophy of the ‘encounter’, the meeting of two people, is propelled by a spontaneous response to a situation and is open to the idea of an immediate creative exchange in the here and now.

The idea is of men and women as personal and social beings but also as ‘cosmic’ beings, that is as people needing to arrange their individual and collective behaviour in order that life can continue not just to survive but to survive with love. This is the goal that Moreno sought and the reason he developed psychodrama. It’s an honouring of creation.

Betty Gallagher points out that ‘poking one’s nose in’ is not a job for the faint-hearted, it takes courage. I agree, but it’s more than courage. It needs a deep commitment to the craft of learning and understanding what’s going on in the world around us. We must bring appropriate techniques into action, adding to and changing them if required. In other words, it means doing our homework, continually training spontaneity and developing creativity.

The following editor’s note gets at the essence of my Montreal story: ‘the importance of living one’s truth in action; the validity of subjective reality; the premise of a here-and-now encounter between individuals (including client and therapist), and a deep egalitarianism’ (Fox 1987:3). The quotation is taken from The Essential Moreno edited by Jonathan Fox. It is a book which is, for me, a wonderful source of understanding. Chapter 1 on The four universals’ is the best introduction to his philosophy that Moreno gave us. Often ahead of his time, when he set down the four universals in 1966, he was very much a man ‘of his own time. In the same year, Paul Abrecht, of the World Council of Churches, called for world economic justice and welfare provision. This was four years before Rachel Carson released Silent Spring (1965), an angry and challenging book demanding that we stop the destruction of our planet. This book was a great voice for the protection of our natural habitat; a demand that we love life.

Two years later Moreno delivered a paper at the University of Barcelona called ‘Universal peace in our time’. The paper contained his famous statement that ‘A truly therapeutic procedure can not have less an objective than the whole of mankind’ (Moreno 1968:175).

Moreno regarded this quotation as his best known opus. It forms the single opening sentence to Who Shall Survive, a title he coined to indicate that the fate of humankind may be imminently at stake. He was ‘of his time’ because the rest were catching up and being more specific about what was wrong.

As we approach the end of the century the industrial nations are crazily in pursuit of materialism while the other half of the world’s people starve. Pollution of the shoreline and seas is greater than ever. Oil tanker disasters are almost commonplace and the leader writers still treat ‘wild life’ as something separate and not affecting our own life.

Professor Trevor Haywood calls it ‘non-logic’ in a brilliant video, Managing for Absurdity: ‘Pollute and poison the world that is essential for our survival in order to manufacture artefacts that are not essential but provide transient pleasure or just marginally improve our convenience’ (Haywood 1992). Journalist John Pilger reminds those young people who, to their credit worked so hard for Live Aid, just where real power lies:

How many of us were aware during 1985—the year of the Ethiopian famine and of ‘Live Aid’—that the hungriest countries in Africa gave twice as much money to us in the West as we gave to them: billions of dollars just in interest payments.

(Pilger 1991:64)

Within the rich nations the gap between the haves and have-nots increasingly widens. Health care deteriorates, crime rises, drug abuse is at epidemic proportions; the arms trade is a ‘growth’ industry and people die by its products both overseas and at home. In Britain we have an ongoing war that has claimed more than three thousand English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh lives.

The politicians come out with the same threadbare ideas: more police, more guns and more military. A retiring military commander hands it back to the politicians saying the only solution will have to be a ‘political one’. It’s Tweedledum and Tweedledee, with death for both Tweedles.

New ideas, new dreams, a vision powered by spontaneity and creativity were never more relevant. Maybe psychodrama’s underlying philosophy is an idea whose time has come? ‘Man fears spontaneity, just like his ancestor in the jungle feared fire; he feared fire until he learned how to make it. Man will fear spontaneity until he will learn how to train it’ (Moreno 1953:47). I would like to update the last sentence of that quotation: ‘Men and women will fear spontaneity and creativity until they learn how to re-train them.’

When we are small children, those life-giving qualities burst forth in all directions. It’s only when the sausage machines of school, jobs and society get to work on us that those gifts of childhood go into retreat. They hide away and we end up fearing them.

Moreno saw his philosophy hidden away in dusty libraries. In the 1990s I see his ideas as relevant to our times and being reconsidered. The students enrolling for training in psychodrama all over the world may be the ones to give them life in the coming century. As new centurians they will face obstacles to creative change in human behaviour that are colossal. The Goliaths are bigger than ever and in the climate of current world reaction the Davids may be smaller.

There is, however, an important difference. The Davids now have Davidas alongside them, and often way out ahead. Women liberated! That, combined with our slingshot of spontaneity and creativity may yet give us the edge.

Third story

In the 1960s when America was considering the bombing of China, Moreno proposed a psychodramatic encounter between President L.B. Johnson and China’s Leader, Mao Tse-tung. He wanted it to be seen on television across the world.

The fact that it didn’t happen does not mean that such encounters cannot happen. It’s true, of course, that there are considerable obstacles. There is a somewhat understa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Part I Encounter as the principle of change Commentary

- Part II The locus and status nascendi of psychodrama Commentary

- Part III The matrix of psychodrama Commentary

- Name index

- Subject index