![]()

1

THE EMERGENCE OF AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF AN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SELF

Robyn Fivush

Our sense of self is intricately linked to our memories of our personal experiences; what happened, how we understand and interpret these experiences and how we link them together into a coherent narrative of how I became the person I am (Fivush, 2010; Habermas & Reese, 2015; McAdams, 2001). The link between autobiographical memory and self is widely accepted, but the depth of this connection is brought home poignantly in the case of individuals who cannot recall their personal past. One specific case, Clive Wearing, was 47 years old when a herpesviral encephalitis virus destroyed much of his hippocampus, robbing him of his memory (Wilson & Wearing, 1995), and leaving him with such a dense amnesia that, in his journals, he wrote, “I am just awake,” “I am now awake,” “I have just woken up,” crossing each sentence out and writing it again and again, in an attempt to express the limited temporal horizon of his consciousnesses. His moment-to-moment being in the world was painfully difficult for him and for all around him, not simply because he could not recall specific events from his past, but because his subjective perspective of his very being did not extend beyond the “now.” Although “being in the moment” is often lauded as healing, in fact, not having any connections to a personal past is unmooring, creating great distress (Pennebaker, 2018).

Indeed, in sharp contrast to Clive Waring’s inability to place himself on the timeline of his own life, most of us live within a highly extended subjective autobiographical consciousness that stretches back into the experiences that have led to this moment, this current self, and stretches into the future, who we will become. Again, this is poignantly illustrated in this very difficult narrative provided by a young woman of 20, Amelia, when asked about the most traumatic experience of her life:

Amelia’s narrative:

The most traumatic experience of my life was the gradual realization that I had been taken advantage of by one of my older sister’s best friends. It took me over half a year to remember. The night that it happened I had consumed too much alcohol, and I didn’t remember the details of a large portion of the night, but I knew that we had had sex. That morning we talked about what had happened, and he somehow convinced me that I had wanted it. I went along with it; I wanted to trust him so much, and I was embarrassed that I had forgotten the night. Over the next months I would get flashes of memory from that night, and bit by bit I started to piece the night together. Finally, just before I graduated from high school, that night was sent back to my memory in a dream. I had said no. I was so upset because deep down I must have known it all along but wasn’t ready to believe it. The morning I owned that memory again I broke off communication with him once and for all … I was so incredibly angry that he had lied to me, angry that I had let it happen after I said no, and mostly angry that I had been helpless to stop the situation in general. I have realized that I really did the best that I could in the situation. I did everything I could, and I know that it wasn’t my fault, so many times my sister and my best friend tell me that. It is just hard to accept that sometimes awful things happen, and you don’t always have control of it. And while it was very hard to accept, I grow stronger every day and I wouldn’t be the person I am right now if I hadn’t gone through that experience and overcome it with all the fight I have in me.

Here we see a woman struggling with multiple subjective perspectives on a traumatic experience, moving from not remembering to conscious memory, layered in different interpretations at different time points, highlighting the changing landscape of her consciousness. Did Amelia recall the event in this way when it happened or has her subjective perspective changed over time as she thought, imagined, dreamed, and discussed this event with others? Is this account of if and how her subjective perspective changed accurate in any sense of the word? These may be important questions, but regardless, what this narrative demonstrates is the subjective sense of a changing interior landscape that has gone through a process of reinterpretations and reevaluations over time. What any individual has in the moment is what we remember now, which is a reconstructed subjective perspective on what we experienced then and how we dynamically recall it over time (Fivush, Booker, & Graci, 2017). In creating this kind of extended subjective perspective, we create meaning from and about our lives; we begin to construct an overarching sense of coherence and purpose as we link events into longer timelines that relate our experiences to our developing values and beliefs (Fivush, 2010; King, Heintzelman, & Ward, 2016).

Amelia’s narrative also relies on input from others, both those she claims denied her subjective perspective, and those who helped her construct a new one. She ends the narrative by explicitly linking this past experience to her current perspective and sense of self. This palpably self-defining autobiographical memory is not a recitation of what happened to her (indeed most of it is not about the event itself at all), but how Amelia’s subjective understanding and perspective on this event has changed over time. This kind of autobiographical consciousness, narrated through multiple, changing subjective perspectives, is a hallmark of autobiographical memory, and, as I will argue in this chapter, it is constructed in social interactions in which narratives are cocreated, negotiated, contested, validated, and confirmed. It is through co-narrating our past with others that our memories move from accounts of what occurred to layered interpretations of what these events mean for self and for others. When we remember the personal past, we do not simply recall what happened; we recall what we now remember happening then as seen through the prism of dynamically evolving perspectives on the event over time. Autobiographical memory is not about the past; it is about constructing and reconstructing the path of subjective consciousness from then to now.

Autobiographical memory, narrative, and language

As the narrative example demonstrates, autobiographical memory cannot be defined simply as personally experienced events. Instead, autobiographical memory is a complex intertwining of discrete episodes, linked together through temporal connections (this, then that), causal connections (this, because of that) and thematic connections (and like this, that) (Habermas, 2011) that create coherence and meaning across experiences (Conway, Singer, & Tangini, 2004; King et al., 2016). In addition to episodic memories, defined by Tulving (1972) as discrete memories of events occurring at a specific time and pace, autobiographical memory includes extended memories (when I was in high school), recurring memories (Sunday dinners with my family) and thematically linked memories (my romantic relationships), most likely organized hierarchically, but certainly organized by personal goals and intentions (Barsalou, 1988; Conway et al., 2004; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Moreover, even single discrete memories extend in subjective consciousness to include before, during, and after, integrated into a coherent “story of me” (Barnes, 1998). It is in this sense that autobiographical memory is shaped by narrative structure. Narratives are canonical linguistic forms that divide the unremitting flow of lived experience into beginnings, middles, and ends, dividing time into meaningful sequences that express human interactions, intentions, motivations, and goals (Ricœur, 1991). Narratives move beyond recounting what happened to describe orientating background, causal connections, and intentional consequences, creating a human drama (Bruner, 1990; Labov & Waletzky, 2003). Moreover, narrative frameworks for understanding human experience are linguistic; they emerge from, and are shaped by, language interactions in which individuals negotiate what happened and what it means (Boyd, 2018).

To be clear, autobiographical memory is not linguistically represented; autobiographical memories are fluid dynamic patterns of multisensory experiences that are constructed and reconstructed over time and contexts (Dudai & Edelson, 2016; Rubin, 2006). But language, in the form of narratives, provides a critical tool for the expression and subsequent understandings of autobiographical memories (Fivush, 2010; Nelson, 2003; Nelson & Fivush, 2004). Language is critical in three ways. First, language allows us to share our personal past with others. Outside of language we may be able to communicate facts about what happened, but it would be substantially more difficult to express our subjective perspective, our thoughts, emotions, and reactions to the event. Even more, it would be difficult to express our changing subjective perspective outside of language or to understand if and how others thought and felt about the event. Thinking about Amelia’s narrative presented above, how might Amelia have expressed her thoughts about the event at the time it happened, how her perspective changed gradually over time, and what her new perspective is outside of language? Second, through the ability to express our experiences, we can also learn about others’ interpretations and evaluations of the experience. Again, in Amelia’s narrative, it is implicit that part of her changing perspective was due to conversations she had had about this event after it occurred. Without these kinds of linguistic negotiations, it is unclear whether her own perspective would have changed in this way. In essence, autobiographical memory relies on narrative in order to create multiple layers of subjective understanding of self and other evolving over time as experiences are told and retold from evolving subjective perspectives (Fivush et al., 2017). Autobiographical memory can only be understood as a developmental process of coming to understand one’s own experiences, and this process begins very early in childhood.

The emergence of subjective perspective

From the moment of birth infants are drawn into storied worlds. Adults whisper stories into infants’ ears, stories of parents and grandparents, family and friends, and how this new life has come into being and what this new life will become (Fiese, Hooker, Kotary, Schwagler, & Rimmer, 1995). As soon as children begin using a few words, parents pull them into reminiscing, “Tell Mommy what happened at daycare,” “Tell Daddy what we did at the park.” Children quickly become active participants in these reminiscing conversations, and by the end of the preschool years, most children are able to tell reasonably coherent narratives about their past experiences (see Fivush, 2007, for a review). There are cultural, gender, and socioeconomic nuances to these early reminiscing conversations that are beyond the scope of this chapter (but see other chapters in this volume, and Fivush & Zaman, 2013; and Wang, 2013, for reviews), but all typically developing children in all cultures develop the ability to narrate personal experiences.

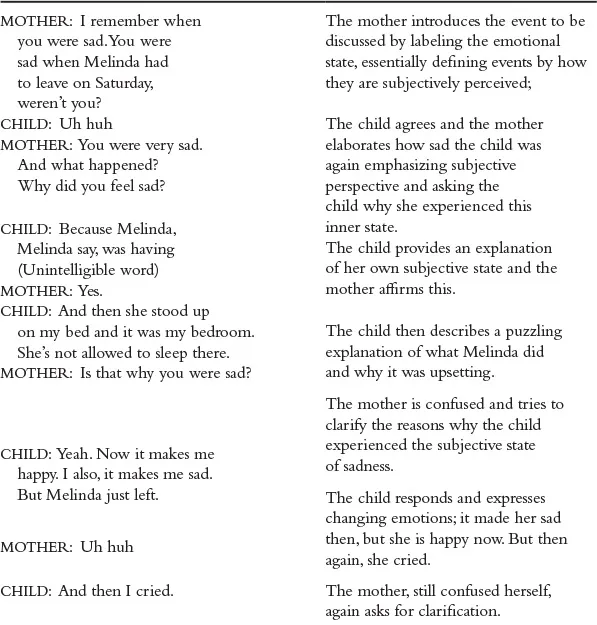

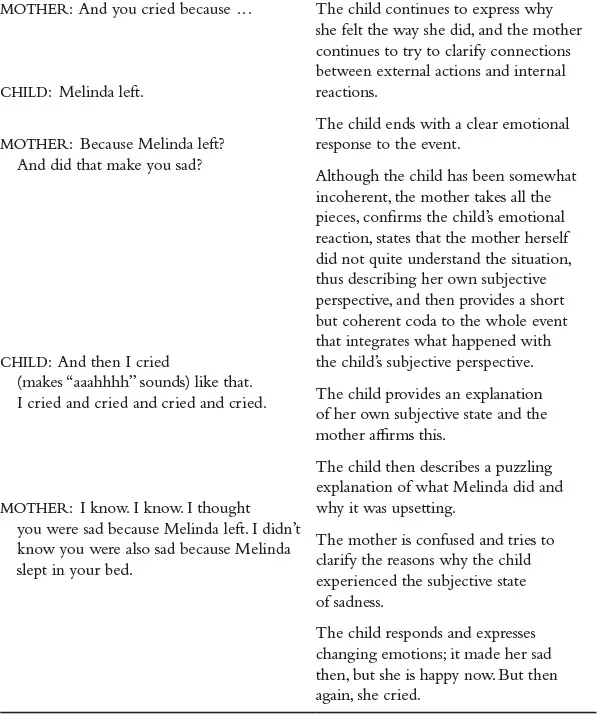

Even in these very early, parentally scaffolded narratives of the past, children are learning how to integrate what happened in the world with their subjective perspective, linking inner and outer, and differentiating self and other. We see this in the following example of a mother and her four-year-old daughter, Sarah, discussing the previous weekend, when Sarah’s best friend, Melinda, slept over. In this excerpt, Sarah is responsive but confusing both in her recitation of what happened, and certainly in her integration of her subjective perspectives both with what happened at the time and how she thinks about the event now. Note how the mother helps Sarah to clarify, understand and integrate the facts of what happened with Sarah’s changing subjective perspective:

Sarah’s narrative:

In this short excerpt from everyday reminiscing between mother and child we see how parents scaffold coherent integrations of inner and outer experience for children through co-constructing coherent narratives. The mother both helps her daughter integrate what she was feeling with what was happening in the world, expresses that the mother herself had a different subjective perspective than the daughter (“I didn’t know”) and ends the narrative with a coherent coda that briefly integrates the daughter’s subjective perspective both with actions in the world and across time.

Table 1.1 describes the multiple ways that early parentally scaffolded reminiscing facilitates both children’s cognitive processing of what a memory is, and how memories help us understand both ourselves and others – essentially building the foundation of autobiographical consciousness (Fivush, 2001, 2010; Fivush & Nelson, 2006; Nelson, 2001). In negotiating what happened, questioning, elaborating, confirming, and negating, mothers are helping their children understand that memories are not copies of events in the world, but representations, that different people can recall different things, and that what the self recalls is unique, one’s own memory, that may be the same or different than what others remember. Further by focusing on internal states – what one thought, how one felt – mothers are helping their children understand that the unique perspective on what happened includes these kinds of subjective interpretations. And although we might agree on what happened (“Melinda slept in your bed”), we may not agree on what we thought or felt about it then (“I didn’t know you were sad”), or how we think and feel about it now (“Now it makes me happy”), thus highlighting that self has a temporally extended subjective perspective on events in the past that may change over time. Through negotiating between what self and other thought and felt then and what self and other think and feel now, children begin to unde...