![]()

1

Ingres and the Arcades

The rejection of the ideal of classicism is not the result of the alternation of styles or, indeed, of an alleged historical temperament; it is, rather, the result of the coefficient of friction in harmony itself, which in corporeal form presents what is not reconciled as reconciled and thereby transgresses the very postulate of the appearing essence at which the ideal of harmony aims. The emancipation from this ideal is an aspect of the developing truth content of art.

T.W.Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

Homère et Phidias, Raphaël et Poussin, Gluck et Mozart ont dit en réalité les mêmes choses.1

Ingres, Écrits sur l’art

One of Ingres’ best-known, clumsy and winningly facile judgements on his great predecessors is his comment on Rubens, a painter whose place in French art as both court artist and rival of academic classicism puzzles him not a little:

chez Rubens, il-y-a du boucher; il y a avant tout de la chair fraîche dans sa pensée et de l’étal dans sa mise en scène.

(there is something of a butcher’s display in Rubens: above all there is fresh flesh in his thinking and something of the butcher’s counter in his mise en scène)2

There is something of a butcher’s display in Rubens.’ Rubens makes Ingres see fresh meat and theatre—flesh in his way of thinking, and the butcher’s slab as his staging for it. Baudelaire shares Ingres’ response; in Les Phares he wrote of Rubens as a ‘pillow of fresh flesh’. If Ingres renders Baudelaire at once both anxious and admiring, then it is perhaps on account of his magisterial absence of freshness and purely marmoreal sensuality. Indeed, in Ingres even pillows are strange; the golden silk cushions of Mme de Senonnes seem to be lit in reverse, with highlights in their hollows and folds, resisting imitation of the sitter’s flesh (Figure 20).3

Graphic, obvious, a little vulgar; in his approach to Rubens’ fleshy nudes and vigorously muscled bodies, Ingres straddles the roles of a professional artist and the amateur or commonplace viewer, whose supposed voice we hear in the Salon pamphlets of the early nineteenth century, and which make such cruel fun of him in his first displays. The coarseness of his reaction perverts his lofty intentions, pinpointing his oddity as a figure for aesthetic integrity. Rubens’ bravura and lavish colour certainly impress him as a spectacle of technique, invention and display. But as an artist whose paragons are Raphael, Mozart and Gluck, Ingres’ pondered reaction cannot but be negative; there may, at all costs, be nothing to learn from Rubens. And Ingres’ students must turn their gaze from his canvases in the Louvre. This scission of potential affect from aesthetic value is one made easy by the Academic conventions for the separate evaluation of colour, drawing and composition that go back to Roger de Piles and, ironically, the temporary triumph of the Rubénistes in the Académie under his stimulus.4 The very viability of measuring an artist’s right to be accorded a determinable quality and hence to a proper and decorous affect in terms of separation and recombination of colour, line and composition guarantees as much.

But if Ingres is defending the Phidian, Raphaelesque or Poussiniste ideal of knowingly composed beauty against this dangerous, libidinously staged abundance, his comment is surely made without conscious irony. For what is the butchery in art, if not the very classical aesthetic that rubénisme had once displaced in the Académie, and which Ingres voices to himself in his notes?

Strictly speaking Greek statues surpassed nature only insofar as they brought together all those beautiful elements that nature but rarely encompasses in a single subject.5

Whatever did become of the remnants of those bodies which have sacrificed their one perfect arm, leg, nose, breast or penis to be combined by the calculating artist in order to produce the perfect imitation of nature? Inadequate, maimed, war-injured, legless or armless wrecks of an aesthetic of plunder, the bodies desecrated by idealism’s unreasonable demands should certainly look more like studies of fragmented corpses by Géricault than the Venus de Milo’s elegant amputations. Should we imagine the name Boucher hidden in Ingres’ meaty fears of Rubens, a displaced insistence on his own role in the regeneration of the French school? Perhaps a fear that the great David’s rococo teacher has passed down a contamination to him, Ingres, David’s great student?

In reprimand for his obtuseness, let’s ask what there is ‘chez Ingres’, what it is that escapes through his formulation of Rubens’ savagery or stall-holder’s aesthetic? One answer could be the missing syllable from the word étal, a verbal currency available to Ingres:

chez Ingres il y a de l’étalage.

‘In Ingres, there’s something of the shop window.’ The phrase is my own, and I find that it makes adequate sense both of the Phidian ideal with its assembly process of perfect parts, and of the fussy look of Ingres’ paintings, even at their most painstakingly simple—the Grande Baigneuse itself is brimming with materials, of which painterly glazes and virtuoso effects are not the least abundant. Jean Cassou in his Ingres of 1947 is entirely seduced by this when he writes of how, in the flat, lightless juxtapositions of the painter’s work, ‘Ingres still has to discover, after his exaltation at the beauty of contours and local colours, the diversity of materials.’6 And étalage helps to name the way in which, at different points of his life’s work, he is so anxious to display his talents and to assemble the fragments of his capacity to shift between incompatible registers of representation from the heroic to the anecdotal, the observed portrait drawing to the more abstracted schemata of classical gestures.

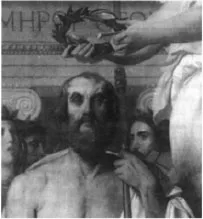

Ingres is forever fiddling with the way things are to look, and this fiddling is not quite the same as preparatory work, though it might well coincide with it—as indeed René Longa realised. Ingres seems as if uncertain about the subject of his paintings. And though he himself insists that it is good to repeat a fine work—‘On m’a fait observer, et peut-être avec justesse, que je reproduisais trop souvent mes compositions…Voici ma raison’ (‘It has been pointed out to me, perhaps with justification, that I reproduce my compositions too often…This is the reason why’)—each repetition tends to shift his relationship to the theme, unfolding the endless proposition that is ‘and if…and if’.7 Consider, for example, the minutiae of his adjustments and reassemblages through his lifetime reworkings of the figure of the Grande Baigneuse, alone or in company, the themes of Virgil Reading the Aeneid, Paolo et Francesca, Antiochus et Stratonice or Roger et Angélica. Figures as important as Virgil himself in Virgil Reading, Francesca’s spouse or even Stratonice, enter and quit the frame from version to version, or drift from one plane to another. Types of body also find themselves in one setting after another, transformed from oriental majesty to Grecian sensuality—again, think only of the versions of Virgil Reading or of Antiochus, or the nude who is here the Odalisque a l’esclave and there the nymph Antiope in all her fleshliness. Think too of that uncompletable exposition of the Phidian ideal that was the Homerides itself, at once one of his most public works, twice over displayed in the Louvre as the copy on the ceiling and as the original canvas on the wall, and also his most private, his last drawing to be worked on before his death. In each reconsideration Ingres’ treasured history of culture and cultural values is disordered and transformed. Which musicians, artists or poets are to be included, and who will have the right to look at whom, to articulate the most directly their descendance from the poet, their closeness to Raphael or Racine? Blind Homer at the origin of art presides over the purety of his heritage as a chaos of indecision, of alternative arrangements, of a disconcerting profusion of choices (Figure 21).8

I want, then, to underline a relation and a homology between étalage and the Phidian ideal of the perfect choice that has a specific allure for a reading of this historical period and the texture of Ingres’ little judgements on Rubens and other aesthetic matters. Such a relation is, roughly speaking, one between an unconscious or an archive of the everyday, which is identifiable with the increasingly merchandise-like quality of art itself and of its markets on the one hand; and, on the other, the duration or atemporality of a deliberated, Academic discourse on art’s making that escapes from or represses this condition through its own recourse to the claim of a pre-modern origin. Ingres, as we have seen, practises an incantatory or magical repetition of this discourse which, typically, he sets in opposition even to the reality of his own work as a painter. The repetition of the antinomy portrait↔history painting is in this sense a fetishistic acknowledgement of his fractured practice through the disavowal of its fracture at the level of incantation. Underlying this relation which resembles that of a conscious/unconscious system of interferences is the homology of the Phidian ideal with that of consumer choice, or the eye’s choices in the increasingly dense visuality of the modern city—amidst which art is one item amongst so many as well as itself multiplicitous in the Salons.9 And, perhaps, it is here in art produced and trapped in the meshes of commerce, that we should seek the phantasmatic imagery of the interaction between the eternal and the ephemeral, rather than in the detached and disembodied gaze of the flâneur. Baudelaire’s mistake in his insistence on Constantin Guys as the bearer of this revelation— that the eternal may be wrested from the ephemeral—lies in his own projection of marginality into an artist and an oeuvre whose relative insignificance met his needs without challenging his aesthetic.10

Moreover the shop window’s combining together of all that is best in a society of increasingly industrial fashion, a society where a Balzac writes for La Mode and, eventually, the Expositions Universelles invite a plenary identification with the commodity, the Phidian principle of choice might as well result in a perfectly dressed bourgeoise as in a finely proportioned statue.11 In an image like Mme Moitessier (1856) we seem to have both. We know the date of the completion of Mme Moitessier from the style of her cap alone. A correspondence of 1937 between Martin Davies, who purchased the painting for the National Gallery, and the Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum mulls over how the tracing of modish fabrics in Second Empire Paris enables us to pinpoint this woman’s relationship with Ingres down to his last chance to complete her in a befitting style of dress. Over the eleven years of her painting, or her ageing, we could speculatively measure the yards of fashionable cloth that have been cut, sewn and thrown away; the trimmings bought, applied, and discarded after a season or a sitting at the most. What a singular effacement of the passage of the present through human gesture is this classically modelled image, copied from the Hercules in Arcadia or some other Pompeian model! Yet which is, in its singular form, neither more nor less than the state of fashion, Autumn, 1856, transience objectified (Figures 22 and 23).12

Importantly, Ingres seems here to have got Baudelaire’s reading of Guys back to front, and ends up with the ephemeral inscribed across the endless and all-inclusive outline of the conventionally timeless that is the classical model or referent. And this is not because he does not belong to the world of Guys and Baudelaire. Rather it is because he does in the closest and most restraining of biographical attachments, in an even more totalising proximity than they.

When Ingres came to Paris to study in David’s studio in 1797, the very first of the great Parisian Arcades, the Passage du Caire, was under construction. The bourgeois shop-window was just beginning to match and then succeed aristocratic modes of provision and spectation, in that fine series of emotional and economic microdramas later to be condensed and memorialized in Balzac’s César Birroteau. This is to say that the Paris to which Ingres came and to which he aspired, and which he left after nine turbulent years for its symbiotic antinom, the unchanging city of Rome, was a city in a state of transformation hardly less spectacular than that of the 1850s and no less complex. Not least the confluence of ideological and economic forces produced by the Napoleonic war economy and social order reinvented and eased the relations of the consumption and production of art into a series of ever more convoluted and endlessly differentiated connections.13 At the same time Ingres’ attachment to the world is structured through the ways in which he acquires the conventions of a classical rhetoric on the one hand, and his urgent desire to quit the little society of provincial, artistic commerce into which he was born on the other.14 A redemption to be effected precisely through this supposedly timeless rhetoric’s sublime powers, which Parisian art education now only uncertainly represents, not least because of its buffeting and marginality in another and more powerful commerce of the modern city.

This rhetoric, which is a basic condition and the equipment of anything above the median of bourgeois education, deeply informs the work of a Baudelaire or a Delacroix. It does so with a more developed linguistic knowledge than that of the relatively ignorant and ill-bred Ingres, who learns by rote, copies out page after page of Pliny, reads translations and fancies himself close to Homer or to Virgil.15 Yet with Ingres this rhetoric never serves to conjure up the immediacy, sensuality and indelible presence of some imaginary referent inside the contemporary orders of locution. It refuses to serve as the index of a utopian potential of the present. Rather, he recuperates it from its death or loss, to strange effect as we are beginning to perceive.

On the contrary, the classical ...