![]() ETHNOGRAPHY AND LANGUAGE POLICY CASES AND CONTEXTS, PART I

ETHNOGRAPHY AND LANGUAGE POLICY CASES AND CONTEXTS, PART I![]()

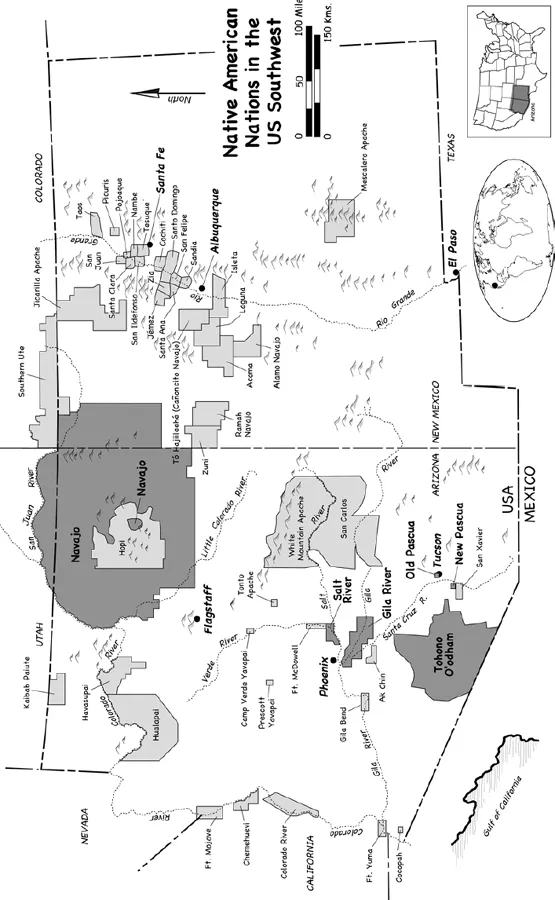

Figure 1.1 Native American nations in the southwestern US (Graphics by Shearon Vaughn).

1 Critical Ethnography and Indigenous Language Survival

Some New Directions in Language Policy Research and Praxis1

Teresa L. McCarty, Mary Eunice Romero-Little, Larisa Warhol, and Ofelia Zepeda

We must … recognize that one cannot change the world if one’s theory permits no purchase on it … A broader, differently based notion of … language in the world … is needed.

(Hymes, 1980a, p. 20)

When Dell Hymes wrote these words, they were aimed at countering the dominant Chompskyan linguistics of the time, which, by emphasizing the generic potentiality of human language, depreciated, in Hymes’s view, “the actuality of language” (1980a, p. 20). In contrast, Hymes offered a “differently based notion,” which, he said, “I shall call ways of speaking” (1980a, p. 20). Only by shifting our gaze from language per se to the role of language in living, breathing speech communities, Hymes insisted, can we transcend “a liberal humanism which merely recognizes the abstract potentiality of all languages, to a humanism which can deal with … the inequalities that actually obtain, and help to transform them through knowledge of the ways in which language is actually organized as a human problem and resource” (1980a, pp. 55–56; emphases added).

Although Hymes penned his essay on the origins of linguistic inequality almost four decades ago, his words continue to teach us about “new directions” in the study of language planning and policy. The seminal critical ethnographer, Hymes found within ethnography not only the methodological tools for understanding diverse ways of speaking, but also an engine for social change. What ethnographers do, he argued – “learn the meanings, norms, and patterns of a way of life” – is precisely what humans do every day; ethnography is “continuous with ordinary life [and] the knowledge that others already have” (1980b, p. 98). Thus, ethnography contains within it the seeds of transformation whereby hierarchies between the “knower” and the “known” can be dissolved; ethnography is, Hymes stressed, a particularly appropriate form of inquiry for a democratic society (1980b, p. 99).

We frame this chapter as a dialogic engagement with Hymes’s early work – his calls for a different way of looking at language that can be fruitfully applied to language policy – and his emphasis on ethnography as both a “way of seeing” (Wolcott, 2008) and a critically conscious, democratizing way of knowing. We ground our analysis in two data sets: a long-term, multi-sited ethnographic study of Native American youth language practices and ideologies in settings undergoing rapid language shift (McCarty, Romero-Little, & Zepeda, 2006; McCarty et al., 2009a, 2009b), and a smaller-scale study led by McCarty at a multilingual, multicultural school.2

Our goals here are three-fold. First, we extend Hymes’s call in the introductory epigraph by framing this analysis within “a broader, differently based notion of language policy in the world” that is fundamentally processual and dynamic as opposed to static and text-driven. Specifically, we take policy to mean not only official acts and texts, but also the undeclared, unofficial interactions and discourses that regulate language statuses, uses, and choices, and that are transacted in everyday social practice (Levinson, Sutton, & Winstead, 2009; McCarty, 2004; Ramanathan, 2005; Schiffman, 1996; Shohamy, 2006; Spolsky, 2004; Sutton & Levinson, 2001). Language policy “can exist at all levels of decision-making about languages,” Shohamy (2006) points out, “as small as individuals and families [who make] decisions about the languages to be used …at home, in public spaces, as well as in larger entities, such as schools” (p. 50). These decision-making processes, we argue, represent de facto language policies.

Second, using this conceptual framework, we peel back the layers (cf. Ricento & Hornberger, 1996) of informal, everyday language policy-making among Indigenous youth to reveal the ways in which “language is actually organized as a human problem or resource” (Hymes, 1980a, p. 20) in the “here-and-now” of their daily lives (Bucholtz, 2002, p. 532). In contrast to views of young people as “not-yet-finished adults,” we attend instead to the “social and cultural practices through which they shape their worlds” (Bucholtz, 2002, pp. 529, 532). We show how youth’s informal policy-making reflects shared yet contested ideologies about language and identity, and how these ideologies are transformed into social practice. While these processes structure language shift, they also afford a window into language planning possibilities that acknowledge and respond proactively to the pressures on contemporary youth language choices.

Finally, we consider how these ethnographically gleaned understandings of language policy enable or “permit a purchase” (Hymes, 1980a, p. 20) on the disruption of the social, educational, and linguistic inequalities they expose.

A Study of Language “That is Fundamental to Education”

A new approach is beginning to emerge into prominence – the study of language that is fundamental to education [in which] one would want to know what kinds of use of language are valued, how these values are exhibited, experienced, and acquired, [and] the relationship between language use in school and … outside of school, where there is continuity, conflict, compartmentalization …

(Hymes, 1980c, pp. 70, 72)

In 2001, we began a federally funded study of language shift and retention among American Indian children and youth in the southwestern US. We were well aware of the grim statistics of Indigenous language loss: of 5.2 million people in the United States who identify as American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian, less than a third report speaking their heritage language at home (Ogunwole, 2006). Put another way, of 175 Native American languages still spoken in the US, only 20 are still being acquired as first languages by children (Krauss, 1998). Native American language endangerment is part of a global loss of linguistic and cultural diversity, with an expert UNESCO panel predicting that 50 to 95 percent of the world’s spoken languages will fall silent by the century’s end (UNESCO, 2003). Most of the “disappeared” languages, according to this report, will be Indigenous languages (McCarty, Skutnabb-Kangas, & Magga, 2008, p. 298).

These realities are of great concern to the Native American communities with whom we work, and in response many have instituted school- and community-based language and culture revitalization programs (e.g., Cantoni, 1996; Hinton & Hale, 2001; McCarty & Zepeda, 2006; Reyhner & Lockard, 2009; Romero-Little & McCarty, 2006). Our goal in this study was to go beyond the projections of language death, and to try to understand how loss of a heritage language is experienced by young people in their daily lives. When, where, and for what purposes do youth use the Indigenous language and English? What is the nature of their communicative repertoires (Gumperz, 1964, 1982; Gumperz & Hymes, 1986)? What attitudes and ideologies do youth hold toward the Indigenous language and English? And how do these ideologies shape youth’s developing lingua-cultural and academic identities?

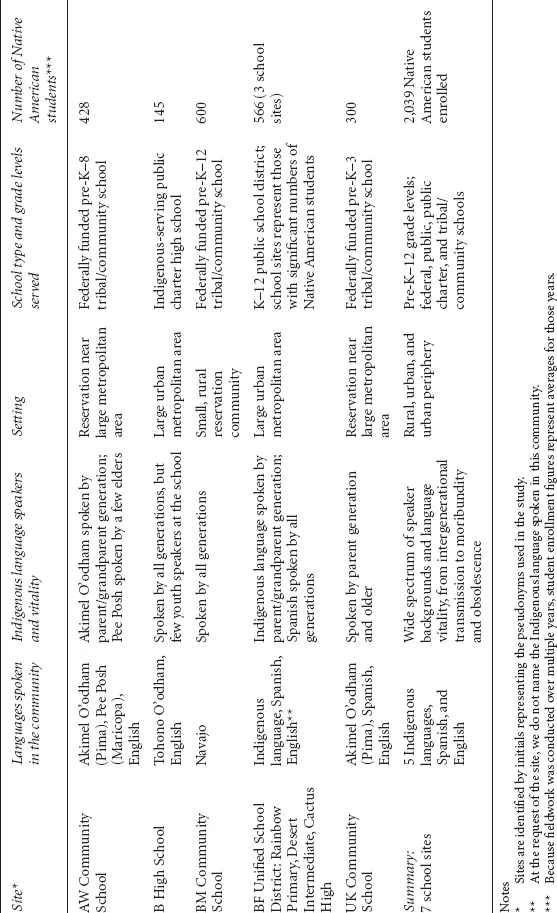

For the next five years, we worked closely with five American Indian communities identified on the basis of our long-term working relationships with them and because their members were equally concerned with understanding the factors influencing their children’s language competencies and academic achievement. As shown in Figure 1.1, the southwestern US is home to some 40 Native American nations, making this a particularly rich and diverse region in which to conduct this research. Our sites reflected this linguistic and cultural diversity. As shown in Table 1.1, this was the breakdown of sites:

1. a Navajo reservation community and pre-K–12 school in which many children still enter school with bilingual abilities, but where Navajo is rapidly losing ground to English;

2. two Akimel O’odham (Pima) communities near a large metropolitan area, in which nearly all Native speakers are middle-aged and older, and where there are a few elderly speakers of a second, linguistically unrelated language, Pee Posh;

3. an urban charter school serving primarily Tohono O’odham teenagers whose heritage language (mutually intelligible with Akimel O’odham) is still spoken in the reservation villages from which students are bused each day, but by fewer and fewer young people; and

4. three schools in a large urban school district attended by children from a diasporic community in which an Indigenous language, Spanish, and English are spoken.3

Altogether, there were seven participating schools enrolling 2,039 Native American students.

Table 1.1 Characteristics of Participating School-community Sites

Each of these communities had experienced major upheavals brought on by Anglo-European invasion and colonization. For the Akimel O’odham and Pee Posh, the diversion of key water resources, missionization, the disruption of traditional settlement patterns, and proximity to a growing urban center profoundly affected the viability of these Indigenous languages. For the Navajo and Tohono O’odham, geographic isolation had exerted a buffering effect, but, like all Native American communities, they too have experienced enormous loss of lands, lives, and livelihoods as a consequence of colonization. At one site, multiple cycles of invasion and colonization led to the establishment of dispersed diaspora communities across colonial-national borders.

In all cases, coercive English-only schooling has been a leading cause of language shift. Our database is replete with references to the impact of colonial schooling and “epistemic violence” inflicted on these communities (Rabasa, 1993, quoted in Collins & Blot, 2003, p. 121). As one parent reported, “My mother saw the bad things that were done … at the mission school, punishing them for speaking their own language, trying to convert them…. She didn’t want us to go through that…. She spoke to us in English” (interview, August 9, 2006). “[T]hey stripped us of who we were as a people,” a young parent said:

Forcing the elders to forget their language,… making them speak strictly English. And when they did come back to the reservation, they were afraid to pass the language on to their kids. And so, if it was passed on …, it was minimal at most.

(Interview, December 8, 2005)

“When I was a young kid,” a Native school staff member recalled, “I got teased [for speaking the Indigenous language]…. And then, that’s when I went to English” (interview, October 17, 2002). “When I was growing up I think I was taught to be ashamed of it,” another educator said; “[t]hat’s stuck with me” (interview, February 13, 2003). As these statements and the data we present show, the legacy of these experiences has been ambivalent language attitudes derived from the “ideological judgments which were part and parcel of the [colonizing] language” (Collins & Blot, 2003, p. 122) – and the socialization of children in English.

Community-based Action Research

A member of a given community … need not be merely a source of data, an object at the other end of a scientific instrument. He/she already possesses some of the local knowledge and has access to knowledge that is essential to successful ethnography …

(Hymes, 1980d, p. 105)

As we have reported elsewhere (McCarty et al., 2006, 2009a, 2009b), the study was guided by principles of participatory action research, in which inquiry is situated in local concerns and community stakeholders are active agents in the work (Stringer, 1999). At each site, we worked closely with teams of Indigenous educators identified as community research collaborators (CRCs). A total of 21 CRCs worked with the project. The CRCs were recruited based on the recommendations of other site personnel and because they were vested in the community and likely to remain once the study ended. The idea was that these individuals would be the critical change agents positioned to apply the research findings to local language planning and education once the study ended. They facilitated entrée and access to community and school activities and events, validated research protocols, assisted with the data collection, and participated in university-accredited coursework on language planning and ethnographic and sociolinguistic research methods sponsored by the study.

Methods

Ethnography is different than field work or “having been there”…. Ethnography is open to questions and answers not foreseen … there is no prestructured model…. One sacrifices certain kinds of reliability for the validity that [comes] with depth.

(Hymes, 1980c, p. 74)

We employed an ethnographic, case study approach, making 80 site visits over five years to collect data, debrief and plan with the CRCs, and report back to tribal councils, school boards, and other local stakeholders. Data collection included demographic records, audiotaped interviews (most in Engli...