1 Urban planning and real estate development: the context

Town planning: an introduction

The modern-day planning system is a post-war invention, with roots that may be traced to the enactment of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947. The notion of ‘planning’ land use goes back further still, arguably as far back as ancient Greece when Piraeus was laid out following a ‘grid-iron’ street plan. Consistent throughout an examination of such urban history is that society affords a measure of regulatory control to the state (i.e. the government) to supervise the use of land. What best distinguishes the 1947 legislation is its scope; principally that it established a comprehensive and universal system of land-use control.

Then, as now, the system served the key function of balancing public and private interests. The creation of the post-war planning system effectively ‘nationalized’ the right of private individuals to develop land by stipulating that planning permission would be required for certain types of development. In return these ‘applicants’ were afforded the automatic right of appeal (to a planning inspector or to the Secretary of State) should consent be refused. This newly created system of town and country planning would exist to secure the interests of the community, in cases where amenity would be harmed. Amenity itself was never defined, and since 1947 to the present it has been interpreted (usually by virtue of legal interpretation in the Courts) in many ways.

The public interest would, therefore, take precedence over the private right to develop land and property (Grant 1992). Nevertheless, the private interest should not be unduly restricted or fettered, and in a variety of circumstances various freedoms, such as the right to extend a dwelling within a certain volume tolerance, would be deemed to fall outside planning control. Today, such freedoms from the need for planning permission are granted by subordinate (i.e. laid before Parliament) legislation, such as contained in the General Permitted Development Order and Use Classes Order (which permit certain building works and changes of use without planning permission).

What has changed since 1947 are the policy outcomes that the system is designed to achieve. In 1947 this meant post-war reconstruction. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, it means ‘sustainable development’, so that by way of example, government policy sets a national annual target that 60 per cent of new housing will be built on previously developed land, including land that is vacant or derelict or currently has potential for re-development (DCLG 2006b) and that the planning system delivers both adaptation and mitigation strategies to respond to climate change.

A growing awareness of sustainability on an international stage has followed from work by the United Nations in hosting global summits in Rio de Janeiro (1992), Kyoto (1998), the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg (2002) and on climate change in Bali (2007). At its most fundamental this subject area sets out to ‘make less last for longer’ (RICS Foundation 2002), so that future generations would still be able to use and benefit from environmental resources. One key area of environmental threat comes from global warming, as the production of carbon dioxide and other emissions (by burning fossil fuels and other industrial processes) traps some of the sun’s energy and produces a rise in global temperature. Global consequences involve dramatic changes to weather patterns, melting ice caps and rising sea levels. At the 1998 Kyoto Agreement (Framework Protocol on Climate Change), the UK government committed itself to reducing the national production of such gases by 12.5 per cent (from a 1990 baseline) by 2012. This target represents a binding legal commitment, although the government have subsequently set a series of more ambitious targets, including raising the bar to a 20 per cent cut in carbon dioxide emissions (the most significant greenhouse gas) by 2010 and setting a more long-term goal to achieve cuts of up to 60 per cent by 2050 (UK Government 2005). Such an aggressive reduction (up to 60 per cent) within the next forty years or so is often put forward as the minimum target to achieve a stabilization of the climate sufficient to prevent extreme weather and associated population movement across the planet (Flannery 2006, Tyndall Centre 2007). Today, world-wide carbon emissions amount to some 3 billion tonnes released annually into the environment. Yet, how can the planning system affect sustainability or, to be more precise, climate change? This is the policy challenge for the system today and in the future. By 2007 the UK government had introduced a guiding set of national planning policy principles (in Planning Policy Statement One) that gave preeminence to the objective of tackling climate change over other policy outcomes (DCLG 2006a). The UK government is committed to the ‘roadmap’ established at Bali (2007) for the future international negotiations necessary to agree more aggressive cuts in carbon emissions.

Sustainability, as a distinct discipline or component of town planning, is only some twenty years old. The 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development (The Brundtland Commission) provided the first and still most enduring definition:

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

While research by the RICS Foundation (2002) reveals considerable disagreement over how to measure sustainability, there is overwhelming scientific and demographic evidence in favour of action now. Statistical evidence is compelling. For example, the United Nations has estimated that by 2030, 60 per cent of the world’s population will live in cities (United Nations 2001). In England today, 90 per cent (47 million) of the population live in urban areas, accounting for 91 per cent of total economic output and 89 per cent of all employment. The powerful and highly influential Stern Review into the economics of climate change (HM Treasury 2006b) concluded that failure to act now on the concentration of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere would lead to serious impacts on economic output, on human life and on the environment.

The planning system is well placed to deliver ‘compact’ cities, based upon efficient land use in which integration with public transport and promotion of mixed-use development discourages dependence on the private car. By promoting and implementing more efficient land use, reflected in density, layout, design, and mix of uses in close proximity, the planning system can make a tangible contribution to climate change and thus affect environmental sustainability.

The need, therefore, to address matters of urban density and layout is pressing. Demographic (i.e. population) change means that over the next generation there will be a significant rise in the number of one-person households, especially amongst younger people. This significant rise in demand for housing presents an opportunity as well as a potential threat for the system. A ‘spectre’ emerges in which planning control is overwhelmed by this volume of development in the following twenty years, a prospect neatly encapsulated by Lord (Richard) Rogers and Anne Power writing in 2000:

We know that in this country [England] alone we may have to accommodate nearly four million extra households over the next twenty years… we can sprawl further round the edges of existing suburbs in predominantly single person households or we can make cities worth living in for those who like cities but do not like what we are doing to them.

(Rogers and Power 2000)

So this potential threat can be made into an opportunity in which development pressure is used to ‘heal’ the city by ‘retrofitting’ a new model of development into the existing urban fabric. The prevailing density of development in our cities must be raised and increasing amounts of urban land recycled. National planning policy sets a headline objective of 60 per cent of new homes on brownland and a national minimum density of 30 dwellings per hectare. The delivery of new housing is being compounded by the market being unable to meet some of the regional targets set by Regional Assemblies. Indeed, in regions like the South East an ambitious target of around 33,500 dwellings to be delivered annually and for the next twenty years appears unlikely to be achieved by housebuilders and housing associations, due to difficulties in releasing sufficient land at the right place and at the right time. How to best create procedural systems that will deliver a renaissance of our urban areas while maintaining many past principles governing the system (such as public participation) and delivering on new policy objectives (like climate change), is another challenge. The UK government, in 2001, instigated a review of the system, which effectively lasted until 2006, with the publication of a Treasury-led review of the planning system (HM Treasury 2004 and 2006a) and an attempt to ‘streamline’ the production of planning policy and the treatment of applications. In 2008 a new Planning Bill made its progress through Parliament, with the introduction of an ‘Independent Planning Commission’, vested with responsibility to make decisions on major infrastructure projects (such as power stations and airports) in light of criticism that the system was too slow in delivering decisions on such matters.

Before considering the implications of such reforms, it is necessary to understand the context within which the town planning system operates. An examination of the past assists in understanding the future because the evolution of urban planning from the late Victorian period exhibits a number of policies, principles and environmental challenges analogous to the present day.

A history of urban planning

Town planning, by its nature, is essentially concerned with shaping the future.

(Ward 1994)

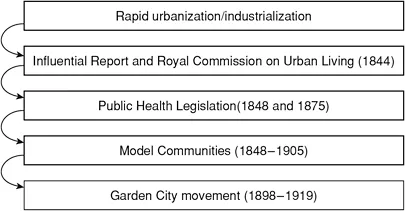

Today, control over land use is increasingly viewed as (one) means of influencing both urban and environmental change. In many policy areas, planning is currently regarded as a reaction against environmental degradation/decay and global warming. For example, if the design and layout of a commercial development harnesses renewable energy sources such as wind power to reduce reliance upon fossil-fuel-derived energy supplies, then, albeit crudely, planning reduces carbon emissions and, in turn, global warming. By contrast, early planning legislation can be traced to the Public Health Acts of the period 1848 to 1875. The genesis of such legislation was the work of people like Sir Edwin Chadwick. Chadwick made a study of urban sanitation and by implication the conditions of the urban working classes in 1842.1 The findings were themselves instrumental in the establishment of a Royal Commission on the Condition of Towns (1844) and subsequent legislation, albeit rudimentary, to establish minimum standards for urban sanitation. The 1875 Public Health Act increased the levels of control so that local government bodies could pass and implement ‘by-laws’ to regulate the layout of dwellings as well as acquiring the power to implement their own schemes following acquisition of urban land. The nine-teenth century witnessed rapid urbanization that affected enormous change across society, economy and environment, and brought with it disease and ill health as a result of insanitary and overcrowded slum housing. Ward (1994) reports that ‘In 1801 the urban population of England and Wales had been 5 million …by 1911 the figure was 36.1 million’.

Industrialization sucked the (rural) population into these new towns and cities. As these industrial urban areas expanded they also merged, giving rise to the new phenomenon of the ‘conurbation’. Pressure mounted to introduce some measure of regulation and, increasingly, urban local government took control over matters of water supply, sewerage and urban layout. A series of local regulations (introduced under powers granted by the Public Health Act of 1875) afforded local control over housing layout to rule out the ‘very cheap and high-density back-to-back building’ typical of the Victorian slum. The grid-iron pattern of late Victorian inner suburbs (at 25 dwellings per hectare) characterized and gave physical form to this newly established regulation. Yet it was not an attempt to ‘plan’ whole districts and to integrate land uses but rather a further attempt to prevent the disease-ridden slum dwellings of the previous seventy-five years by provision of sanitation within, and space around, individual dwellings.

The notion of planning entire areas is perhaps best traced to the Garden City movement of the turn of the twentieth century. The ‘Garden City’ was something of an umbrella term, encapsulating many planning and property development principles in the quest for an environment based upon amenity or quality. Further, the Garden City represented a reaction against the squalor of the Victorian city, just as today the planning system strives to create sustainable environments as a reaction against environmental degradation.

The Garden City idea and the movement it spawned were crucial precursors to the town planning movement in Britain.

(Ward 1994)

Howard published his ‘theory’ of the Garden City in 1898.2 This was based on the notion that a planned decentralized network of cities would present an alternative to the prevailing Victorian system of urban concentration. The Garden City was created on the development of four key principles. First was the finite limit to development. Each city would grow by a series of satellites of 30,000 population to a finite limit of around 260,000. A central city of 58,000 would provide specialist land uses like libraries, shops and civic functions. Each satellite would be surrounded by a greenbelt. Second, ‘amenity’ would be of fundamental importance so that open space and landscaping would provide valuable recreational and aesthetic benefit. Third, this pattern of development would create a topography based on the notion of a ‘polycentric’ (many-centred) social city with a mix of employment, leisure, residential, and educational uses within close proximity. Finally, all land would be under ‘municipal control’, so that the appointed Garden City Company would acquire land, allocate leasehold interests and collect rents. Initial capital to create the company would be raised from the issuing of stocks and debentures. In effect a development company would be created that would be managed by trustees, and a prescribed dividend would be paid (a percentage of all rental income to the company). Any surplus accrued would be used to build and maintain communal services like schools, parks and roads. Howard’s theory has been encapsulated as a kind of non-Marxist utopian socialism (Miller 1989) seeking at the time a reform of land ownership without class conflict.

Such a theory was itself derived from a combination of sources, in particular the concept of land nationalization in the late nineteenth century. This involved the creation of social change through land ownership. Further, Howard was affected by the aesthetic ideas of socialists such as William Morris and the ‘model communities’ of Victorian philanthropists such as Sir Titus Salt (Saltaire, Bradford 1848–63), George Cadbury (Bournville 1894), William Lever (Port Sunlight 1888), and Sir Joseph Rowntree (Earswick, York 1905). All these projects conceived the notion of the utopian industrial suburbs to improve the conditions of the workers. Saltaire was noted for its communal buildings (schools, institute and infirmary), Bournville for its extensive land-scaping and large plot size, Port Sunlight for its good-quality housing, and Earswick for its spacious layout.

In 1903 Howard embarked on the development of Letchworth in Hertfordshire, with Welwyn Garden City to follow in 1920. A Garden City company was established and remains today. The town plan showed a group of connected villages, linked to a civic centre and separated from an industrial area. The concept of ‘planned neighbourhood’ was born.

Letchworth was probably the first English expression of a new town on a large scale.

(Smith-Morris 1997)

Two architects previously employed at Earswick, Raymond Unwin (1863–1940) and Barry Parker (1867–1947) added design to Howard’s theory, producing medium-density (30 dwellings per hectare) low-cost cottage housing in tree-lined culs-de-sac (a layout first created at Bournville). The vernacular design exhibited the strong Arts and Crafts influences of William Morris (1834–96), C.F.A.Voysey (1857–1941), Richard Norman Shaw (1831–1912) and Philip Webb (1831–1915). Morris had viewed ‘the home as a setting for an enlightened life and projected its virtues outwards to embrace community’ (Miller and Gray 1992). Arts and Crafts architecture emphasized the picturesque, using gables and chimneys, and reviving traditional construction, including timber framing. Raymond Unwin developed the ‘local greens’ (or village greens) and culs-de-sac used in Letchworth and also in Hampstead Garden Suburb (North West London).

Other schemes were to follow, notably Wythenshawe (Manchester) and Hampstead Garden Suburb. Howard had taken the rudimentary public health legislation of 1848 and 1875 and produced the ‘master planning’ of an entire area, based upon design innovation, affordable housing, mixed use and social ownership. Such principles are of great importance today as government policy sets out to engender an urban renaissance. A summary of developments leading to the establishment of the Garden City movement is set out in Figure 1.1.

The key principles upon which the ‘model communities’ of the late nineteenth century—and the Garden Cities/suburbs of early twentieth-century—were based are set out in Table 1.1. When considering the density as displayed (dwellings per hectare), it is worth comparing these data with the 1875 by-law figure of 25 dwellings per hectare and the post-war norm of between 15 and 20 dwellings per hectare. Historically, housing densities have fallen progressively over the last 125 years or so. What is perhaps most interesting is that they have fallen from the Victorian city, where overcrowding prevailed, to the low-density post-war suburbs of volume (i.e. mass-market) housebuilders. In other words, they have fallen from the insanitary to the inefficient. Up to 2000, new housing layouts were wasteful in their use of land. By comparison, Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City, as originally built, involved densities in excess of 30 dwellings per hectare yet maintained a leafy environment in which open spaces and amenities predominated. Much can still be learnt from examination of environments like this in the building of pleasant medium- to high-density housing without the need for a return to the high-rise schemes of the 1960s.

Figure 1.1 Development of the Garden City

So at the beginning of the twentieth century a series of urban planning experiments pointed the way forward. A statutory system lagged very far behind. The first town planning legislation (the Housing, Town Planning, etc. Act 1909)3 introduced ‘town planning schemes’, which allowed councils to plan new areas, mostly for future urban extensions or suburbs—although a poor take-up resulted in only fifty-six schemes being drawn up in the first five years (by 1914). Yet in the inter-war years ‘the town extension policies which had been embodied in the 1909 Act were now being implemented on a vast scale’ (Ward 1994). Further legislation was enacted in 1919 with the Housing, Town Planning, etc. Act. This legislation incorporated a series of design space and density standards recommended by a government committee the previous year (the Tudor Walters Report) that importantly endorsed a housing model based upon Garden City densities of 12 houses per acre (30 per hectare). The Act imposed a duty on all towns in excess of 20,000 population to prepare a town planning scheme, albeit that take-up was again poor.

Table 1.1 Principles of early town planning

The 1930s witnessed a rapid growth in private speculative development on the urban fringe. Four million dwellings (some estimates are as high as 4.3 million) were constructed in the inter-war years, peaking at over 275,000 in 1935 and 1936 alone. Of all inter-war dwellings, 58 per cent were built by private speculators. By the 1930s the ‘erosion’ of land from agricultural to urban use stood at some 25,000 hectares per annum. This boom cont...