![]()

Part I

Identity, strategy, and the environment

Lin Lerpold, Davide Ravasi, Johan van Rekom, and Guillaume Soenen

How do organizational identities affect individual and collective behavior in organizations? How do members’ beliefs and aspirations about what their organization is (or should be) shape the way decisions are made, strategies are formulated, and policies set up and enforced? Past research shows that members’ identity beliefs and aspirations frame how they interpret changes in society, technology, and the industry – especially to the extent that these changes are perceived as posing a threat to the preservation of a collective sense of self – as well as how they respond to these changes by formulating new strategies or adapting existing ones.

Organizational identity is often invoked by members to support or justify decisions that are perceived – or presented – as crucial to the maintenance of features, without which “our organization would not be the same.” At times, however, changes in the external environment may challenge members’ confidence in the viability of current conceptualizations of their organization, requiring them to re-evaluate their beliefs and aspirations as they formulate new strategies for the organization. Often, as organizational strategies need to adapt to a changing industrial landscape, so too do the identity beliefs and aspirations that underpin and support strategies. Strategy formulation, then, becomes a process where members’ beliefs and aspirations must be made explicit, re-evaluated, and reconciled with changing environmental conditions.

However, as organizations engage in substantial organizational and strategic changes, it is not unlikely that conflicts arise regarding the appropriate course of action. At times, as the case of SNCF (see Chapter 2) shows, conflicting views and positions may rest on different beliefs and aspirations about what the organization is and should be. For instance, people in different units or with different professional backgrounds may develop partially diverging views and aspirations. These diverging views – or, as they are sometimes called, multiple identities – are often unarticulated, but they may underlie internal tensions or, occasionally, give rise to heated conflicts.

The relationship between identity, strategy, and the environment, then, appears to be a dynamic one where all three elements are interrelated and have important iterative influence on one another. In the remainder of this part of the book, we will briefly introduce how organizational identity dynamics influence strategy making in organizations. The issues we raise will be illustrated and discussed more fully in the cases that follow.

ORGANIZATIONAL IDENTITY AND STRATEGY FORMULATION

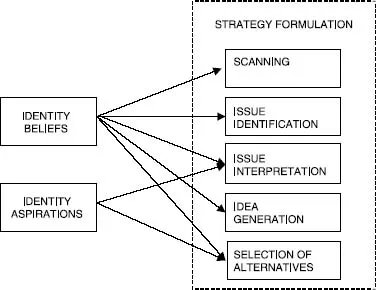

The formulation of organizational strategies can be understood as an iterative process involving the collection of information about the environment (scanning), the selective focus of attention on some of this information (attention), the attempt to make sense of this information (interpretation), and the development of potential responses.1 All these steps are influenced by interpretive schemes that help people assign priority to the various events they are facing, frame their sense-making activity, and guide their selection of appropriate courses of action. These sense-making/interpretive schemes are related to organizational members’ current identity beliefs and, to some extent, their identity aspirations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Organizational identity and strategy formulation

Strategy formulation usually starts with the acquisition of information from and about the external environment – a process that has been termed “environmental scanning” (Aguilar, 1967). However, with overabundant information – and a limited capacity to collect, store, and process that information – managers engaged in formulating strategy have to make choices about what kind of information is salient to them and what information sources are appropriate. Their choices are also guided by their beliefs about “what their organization is” (Nardon and Aten, 2004). The case of the three spin-offs of AT&T described in Part I illustrates how managers’ different conceptualizations of the organization lead them to gather information about different reference groups – in this case, competitors – with repercussions for the following stages of the process.

However, managers do not attend equally to all the information they gather. While some pieces of information are noticed, others are more or less consciously ignored. In this respect, identity beliefs provide a reference for assessing the importance of an event and the extent to which it is worthy of attention (Dutton and Dukerich, 1991). In particular, an event that seems to challenge or contradict collective identity beliefs is likely to become an “issue” – i.e., an event that members collectively acknowledge as threatening their collective sense of self, and as deserving a response. Later in this section, we will call these events “identity threats.”

Identity beliefs, however, do not merely affect the collection of information, they also influence how members process information. They provide a cognitive framework for members’ interpretations of events and their subsequent action (Gioia and Thomas, 1996). More generally, organizational identity helps members of an organization relate to the broader organizational context within which they act, and to make sense of events in relation to their understanding of what defines the organization (Fiol, 1991). Jane Dutton and Janet Dukerich's (1991) study of the New York Port Authority shows how identity beliefs tend to constrain the meanings that members give to an issue; they help distinguish aspects of the issue that pose a threat to the organization from those that do not, and they eventually guide the search for solutions that can resolve the issue. At the Swedish bank, Handelsbanken, for instance, the diffusion of internet technology and “e-banking” was initially viewed as a threat to the independence of local branches and to the preservation of close direct relationships with customers – two features that were collectively perceived as central and enduring to the organization. Members’ determination to preserve these features eventually led to the development of innovative solutions that reconciled established identity beliefs with adaptation to a changing competitive environment. The case is described in more detail in Chapter 4.

Current beliefs, however, are not the only identity-related frames affecting strategy formulation. Based on their investigation of how top managers in higher education institutions make sense of changes in modern academia, Dennis Gioia and James Thomas (1996: 371) argue that “under conditions of strategic change … it is not existing identity or image but, rather, envisioned identity and image – those to be achieved – that imply the standards for interpreting important issues.” Whenever environmental conditions are interpreted as requiring substantial changes in the organization, identity aspirations – “what we would like to be as an organization in the future” – may in fact override identity beliefs – “what we believe we are now” – in driving the formulation of new plans. The identification of an “identity gap” between current beliefs and future aspirations (Reger et al., 1994) may thus be crucial to the development of new strategies that effectively reconcile beliefs, aspirations, and external conditions.

ORGANIZATIONAL IDENTITY AND STRATEGIC DECISIONS

The idea that identity claims and beliefs are invoked by organizational members to help them select among alternative courses of action is as old as the concept of organizational identity itself. In fact, Albert and Whetten's conceptualization of organizational identity was initially formulated to explain an organization's surprisingly heated reaction to a proposed 2 percent budget cut, a change that should have been experienced as relatively insignificant (Whetten, 1998). The proposed change raised fierce emotions and heated debates, as it was perceived as leading to the “uncontrollable erosion of the organizational, and by inference personal, identity” (Whetten, 1998: viii). As one of the participants in the discussion observed:

Would important constituents still think of us as the University of Illinois if we cut out the aviation program, or cut back on agricultural extension services?

(Whetten, 1998: viii)

According to Whetten, organizational self-definitions became a “court of last resort,” invoked to support or justify decisions that cannot be settled on purely technical or economic grounds. A similar phenomenon can be observed in the case of the Swedish truck manufacturer, Scania (see Chapter 1). At Scania, organizational members refused to discontinue the production of bonneted cab trucks for years, regardless of commercial considerations, because this particular design was believed to be central to how both employees and customers perceived and defined the organization.

More generally, identity issues are likely to be raised or invoked whenever alternative courses of action seem relevant to or incompatible with existing identity claims and identity beliefs (Whetten, 2006). During major transitions in the organizational lifecycle, for instance, organizational identity may serve as an anchor point to guide major decisions in the absence of more “objective” criteria, such as technical superiority or economic efficiency. Organizational identity issues are also likely to be raised when there are events and actions that imply an alteration of important identity referents, such as the diminishing relevance of local branches as a result of the spread of e-banking described in the Handelsbanken case. In Part II we will refer to these potentially disrupting events as “identity threats.”

ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES, IDENTITY THREATS, AND ORGANIZATIONAL RESPONSES

Organizations and their members respond actively to external or internal events that they perceive as threats to their identity beliefs, identity aspirations, and/or the image of the organization. A discrepancy between how members believe the organization is perceived externally (what scholars refer to as construed external images) and how members perceive the organization (their identity beliefs) or wish it were perceived externally (their desired image) is likely to trigger a reaction aimed at countering threatening events and representations, and at preserving collective internal and external perceptions of the organization (Ginzel, Kramer, and Sutton, 1993). Unfavorable images of their organization may threaten members’ sense of self and negatively affect their psychological well-being as well as their identification with and commitment to the organization (Dutton, Dukerich, and Harquail, 1994). Furthermore, a deteriorating image may eventually undermine the organization's very survival by decreasing the willingness of critical resource holders to support the organization (Scott and Lane, 2000).

Usually, organization members respond to these “image threats” by engaging in impression management tactics to reaffirm the identity of the organization (Ginzel, Kramer, and Sutton, 1993; Sutton and Callahan, 1987) or by adopting “face-saving” strategies (Golden-Biddle and Rao, 1997) aimed at preserving or restoring collective perceptions and self-esteem when confronted with disrupting events. However, insofar as organizational images provide members with feedback from external stakeholders about the credibility of the organization's claims, a serious discrepancy between internal beliefs and external perceptions may undermine members’ confidence and induce them to re-evaluate their beliefs. They may do so by asking themselves “Is this who we really are? Is this who we really want to be?” (Whetten and Mackey, 2002).

In fact, external pressures increase the likelihood that organizational members will reflect explicitly on identity issues (Albert and Whetten, 1985). Of particular relevance are events that are associated with shifting external claims and expectations about the organization, and/or which seem to challenge the prospective viability of current conceptualizations of the organization and of the strategies that rest on them (Ravasi and Schultz, 2006). Under such circumstances, these events become real “identity threats,” as they are perceived as demanding substantial alterations to core and distinctive organizational features and as challenging the sustainability of organizational identities (Barney et al., 1998). The cases of Handelsbanken in this section (Chapter 4), Bang & Olufsen (Chapter 6), Statoil (Chapter 7), and Industrifonden in the next (Chapter 5) illustrate how relevant identity threats can be to strategy formulation and organizational survival.

![]()

Chapter 1

Scania's bonneted trucks

Olof Brunninge

What actually shapes a company's strategy? The normative literature in the field (e.g., Porter, 1980) emphasizes the importance of rational managers, calculating the economic consequences of different options and choosing the one that offers the highest possible return. Critics of this view have remarked, however, that strategy making is not that simple in practice. A variety of aspects that go beyond purely economic calculations need to be taken into account in order to understand strategy processes in their full complexity (Mintzberg et al., 1998). Organizational identity is one such aspect. It has been said to serve as a “beacon for strategy” (Ashforth and Mael, 1996: 32), providing strategic direction to the company. Albert and Whetten (1985), in their classic paper, characterize identity as a court of last resort in the strategy process. In cases where companies struggle with a strategic decision, the question about the company's identity can be decisive for which strategy is eventually chosen. How clear is the guidance identity offered and how strong is this guidance in a situation where identity clashes with more economically oriented rationales in the strategy process? Such questions become critical when tensions arise around controversial strategic issues.

At the start of the new millennium, the Swedish truck manufacturer Scania was one of the few remaining independent companies in the industry. The firm had a tradition of more than a hundred years of truck manufacture and strived to position itself as the premium brand in the industry. A particular characteristic of the company was its so-called modular system, meaning that trucks were assembled from a relatively limited number of components. Thanks to standardized interfaces, the components could be combined in numerous ways like the building blocks from a child's toy.

The present case tells the story of a specific cab design, the bonneted T-cab, which has come to symbolize the distinctiveness and legendary status of Scania trucks. Around the turn of the millennium, there was an internal debate at Scania between proponents of the T-truck and those opposing it for commercial re...