- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Future Transport in Cities

About this book

Cities around the world are being wrecked by the ever-increasing burden of traffic. A significant part of the problem is the enduring popularity of the private car - still an attractive and convenient option to many, who turn a blind eye to the environmental and public health impact. Public transport has always seemed to take second place to the car, and yet alternative ways of moving around cities are possible. Measures to improve public transport, as well as initiatives to encourage walking and cycling, have been introduced in many large cities to decrease car use, or at least persuade people to use their cars in different ways.

This book explores many of the measures being tried. It takes the best examples from around the world, and illustrates the work of those architects and urban planners who have produced some of the most significant models of "transport architecture" and city planning. The book examines the ways in which new systems are evolving, and how these are being integrated into the urban environment. It suggests a future where it could be mandatory to provide systems of horizontal movement within large-scale development, using the analogy of the lift, upon which every high-rise building depends. In so doing, future cities could evolve without dependence on the private car.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart I

The transport situation today

Chapter 1

Introduction

By the year 2000 many people believed that cities would be transformed. Streets would be quiet, safe places in which to walk and public transport would be a delight to use, being both convenient and affordable. In the cities of Western Europe, from which this book largely draws its material, some transport systems have, at least, partly achieved this. These cities are now better places in which to live and work, where people can bring up their kids safely and in good health. There has never been more of a demand by the public than today for a better environment in which to bring up their children. The ‘image’ for the city in which they live has become important for them – as has the ambition that, the city should be a ‘delight’ to be in, and a place to enjoy, rather than an environment torn apart by traffic.

In all cities an important factor affecting the environment is the numbers of cars per head of population (Europe, with a population density of 344 people per sq. mile, has 116 million cars while the United States (excluding Alaska) with a population density of 78 people per sq. mile has 141 million cars). How the car has been absorbed and dealt with by cities is discussed in this first section.

1.1

Set for the film Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926. Possibly influenced by his first visit to New York, this portrayed life in a city where the workers lived and worked underground under protest, while their rulers enjoyed living above ground and travelled by various systems of transport.

Set for the film Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926. Possibly influenced by his first visit to New York, this portrayed life in a city where the workers lived and worked underground under protest, while their rulers enjoyed living above ground and travelled by various systems of transport.

The present situation

The predictions of car ownership in the UK are that a rise of 20 per cent could occur in the next ten years. Single-car ownership is increasing in the more affluent families to two or more cars. Although people love their cars, 50 per cent of the population still either do not own a car, cannot afford one, don't want one, or are too young – or too old – to drive. The effect on life in cities caused by traffic is already alarming. Three thousand children in the UK are killed or injured in an average year, which is the second highest accident rate in Europe, and vehicle exhaust is estimated to affect 200 million people in urban areas. According to the World Health Organisation 15,000 Italians die annually from smog-related illness. Noise levels too are estimated in Europe to affect over 80 million people. Pollution from traffic is also likely to have an effect on global warming, but the exact extent of this has yet to be established.

1.2

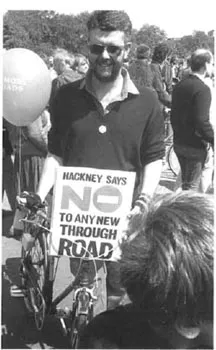

Grass roots opposition to more road building has questioned the need for more roads, which simply bring in more traffic. This protest, organised by residents of Hackney, an east London borough, concerned the East Cross route which was subsequently built.

Grass roots opposition to more road building has questioned the need for more roads, which simply bring in more traffic. This protest, organised by residents of Hackney, an east London borough, concerned the East Cross route which was subsequently built.

Some of the problems of traffic in cities are being dealt with by authorities with varying degrees of success. Depending on the country these may be summarised, somewhat simplistically, into five approaches towards the problem:

- There is a serious and effective grass-roots opposition in most countries to more urban road-building on the basis that more roads mean more traffic.

- Within residential areas there has been the development of traffic calming and town yards.

- Controls on parking within city centres has effectively reduced and controlled the amount of traffic entering cities.

- Planning laws are banning more out-of-town shopping centres or random car-oriented development.

- Public transport has been maintained and improved, without which none of the other measures would be effective.

In spite of these measures there remains the nagging problem associated with continuing car growth, the political strength of the car lobby and a public wanting to use cars. People love their cars. Cars are a retreat from the real world, which partly accounts for their popularity. Cars also afford a degree of comfort and privacy for the user which public transport does not, and can take the driver where he or she wants to go. As a result of this, the car has caused the most problems to city life. It is here that alternative ways must be found of providing transport which is good enough to get people out of their cars, as well as providing a better service for those without them.

Cars in cities: what is happening

In the 1960s a project by an American architect, Victor Gruen for Fort Worth, Texas, represented a prototypical image for the planners of many European cities after the Second World War. Gruen's plan showed a city centre with a pedestrian-only centre about 1 km square, with small bus-trains serving as local transport. The deck was to be serviced from basement level and ringed by a giant freeway system, feeding into multi-storeyed parking for 60,000 cars. Many German cities were rebuilt along similar lines, except that the ring roads were smaller and public transport by bus or rail still served the centres. Most of the city centres adopted pedestrian-only areas for their main shopping streets but built multi-storeyed car parks around them because at that time it was believed essential to their survival.

These parking buildings, together with the inner ring roads built later, proved not only to be inadequate for the numbers of cars entering and wanting to park, but frequently occupied valuable land as well as generating unwanted traffic. In Essen, for example, the ring road serving the parking has had to be expensively bridged in order to connect the centre with the surrounding neighbourhoods. Such roads became nooses around the centres, overscaled and isolating them from the surrounding neighbourhoods. Work on Munich's only partly built inner ring road was, in fact, abandoned once the populace realised what it was going to do to the city centre.

Park and ride

In European cities it was found that some people still wanted to live close to the centres, if not in them. As car ownership increased so parking became insufficient and much of it, principally commuter parking, was moved to the periphery, accessible from outer ring roads, smaller than in Gruen's plan. More importantly it became obvious to site this parking next to rail or light rail routes which people could use to reach the centres more quickly than driving. Hamburg, for example, froze parking in the centre and constructed, at least one well-planned park and ride garage adjoining its subway line, providing ticket machines at every level with lifts feeding directly down to platform level. But this attention to detail is rare. All too often, for reasons of cost, where land was cheap, park and ride was built at surface level around the suburban stations, creating a barrier for anyone walking to the station. San Francisco's BART metro planned many of its suburban stations in this way, regardless of the environmental implications, but is now rectifying this by beginning to build multi-storeyed parking, as well as offices, on sites of former car parks. Moreover, due to the presence of the station, the land values have risen.

Light rail today is increasingly used to serve park and ride commuters and shoppers although operators are rarely obliged to pay the high price of multi-storeyed parking (see Figure 2.10). Because light rail is so often retrofitted into an existing community (such as has occurred in Vancouver with its Skytrain, or in Croydon with London's Tramlink), park and ride car parks are deliberately omitted at stations in order to reduce the traffic generated by them. Instead passengers reach stations on foot, by cycle or by bus – or are simply dropped or picked up at stations (’kiss and ride’).

1.3

Van poolers at 3M factory, Minneapolis. A popular means of transport for suburban commuters in North America, with vans often paid for by the factory and driven by the workers, with priority space given for parking. Courtesy: 3M, Minnesota.

Van poolers at 3M factory, Minneapolis. A popular means of transport for suburban commuters in North America, with vans often paid for by the factory and driven by the workers, with priority space given for parking. Courtesy: 3M, Minnesota.

Not all countries have followed this practice. France, for example, which has had a long-standing honeymoon with the car, continues to build extensive multilevel parking around its stations. Some 100,000 car spaces are provided on the periphery of Paris, often without parking controls in neighbouring communities. For example at Torcy, served by the Regional Express metro line (RER), the multi-level parking for 1000 cars is unused and commuters simply park free in the surrounding streets. Within the city centres, any new building in France will normally be required to provide for layers of parking below, and architects take this as a matter of course, giving their buildings, in cross section, the appearance of an iceberg (see Figure 7.3). It was not for nothing that President Pompidou decreed ‘it is necessary to adapt Paris for the automobile’ and did so, destroying both banks of the Seine with motorways in the process.

This approach contrasts with policies for new office building in the City of London where developers are not required to provide for parking unless their clients feel it is necessary to pay the high cost of doing this. What should also be done is to require, as occurs in France, that anyone working in the centre employing more than ten people contribute towards the cost of the transport infrastructure by enacting a tax (le versement public) based on a percentage of the wages paid. This tax raises substantial sums of money in France to help finance new transport infrastructure. For example in Strasbourg £34 million is raised annually for subsidising public transport and £61 million was raised by this means to help finance the construction of the light rail system, which cost £230 million (Hass-Klau et al., 2000).

The insatiable demand for parking space, and the traffic congestion caused by cars looking for parking space, has now resulted in planning authorities, in parts of North America, enacting controls to limit the amount of car access to new developments, before planning permission is granted. Employers in some areas of California, for example, are required to reduce parking by encouraging their employees to reach their workplace by sharing cars (called car-pooling) or alternatively by providing them with small self-driven buses to serve groups of fellow workers living in the same area (called van-pooling). Workers too, may be given free travel passes for use on trains or buses. At Boots, in Nottingham UK, for example, over £250,000 a year is spent on providing special buses to bring worke...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I The transport situation today

- Part II Transport and the future city

- Part III The new transport technology

- Comparative systems

- Selected bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Future Transport in Cities by Brian Richards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.