1

Introduction

Why India is a democracy and Pakistan is not (yet?) a democracy

It is rare for two countries as similar as India and Pakistan to have such clearly contrasting political regime histories. These are large, multi-religious and multi-lingual countries that share a geographic and historical space that gave them in 1947, when they became independent from British rule, a virtually indistinguishable level of extreme poverty and extreme inequality. All of those factors militate against democracy, according to most theories, but democratic systems were the next step from the gradually liberalizing institutions of the state that the British had grudgingly accepted, in response to nationalist-movement demands. In Pakistan, democracy did indeed fail very quickly after independence. It has only been restored as a façade for military–bureaucratic rule for brief periods since then, including the present. After almost thirty years of democracy, India had a brush with authoritarian rule, in the 1975–7 Emergency; but, after a momentous election in 1977, democracy has become stronger over the last thirty years.

Why is it that after sixty years of independence Pakistan is now, and has mainly been, an autocracy, while India is now, and has mainly been, a democracy?1In 1947 these two countries were fraternal twins, sharing a deep history of “Indian” civilization, with a largely overlapping genetic and linguistic heritage, and a history of struggle to be free from British rule. They also inherited much of the colonial state, including its legal system, its bureaucratic system, and its constitutional structure. Both countries smoothly started functioning as democracies, with elected provincial assemblies (albeit by the 15 percent or so of adults who were enfranchised) and an indirectly elected constituent assembly, which was divided, with the two parts serving also as a parliament for the successor country.

Many scholars and other experts believed that neither country would develop a stable democracy. Both countries were so desperately poor, so grossly inegalitarian in practice and belief, and so prodigiously multi-lingual if not multi-national that sustaining a democracy would be very difficult if not impossible. Pakistan’s history indeed conforms to the expected normal pattern of “political development” (see Riggs 1981 for a wonderful dissection of that term’s meaning), in which an initial gift of a democratic system from the colonial power breaks down fairly quickly, with either the military or a single party headed typically by a charismatic leader putting an autocracy in place.

India is thus the deviant case. As Michelutti (2008: 3) has summarized it: “‘Indian Democracy’ carries on working despite the poverty, illiteracy, corruption, religious nationalism, casteism, political violence, and disregard of law and order.” Rajni Kothari (1988: 155) argues that “India is a deviant case in a much more fundamental sense, in that most if not all the threats to democracy in India come from the modern sector, and from the pursuit of State power by this sector for steamrolling tradition and pluralities in an effort to make the country a modern, united, prosperous and powerful polity.” But democracy is now more than just a system for organizing the government; according to Yogendra Yadav (1999b: 30):

Indeed, democracy in India has been “accepted and legitimated in the popular consciousness” (Michelutti 2008: 4).

Some resolve the question of India’s deviance by claiming that India is not “really” a democracy, or not really a “substantive” democracy. Others are still waiting for the anomaly to be resolved by India falling apart, or succumbing to a (fascist) Hindu nationalism or a (left) revolutionary takeover.

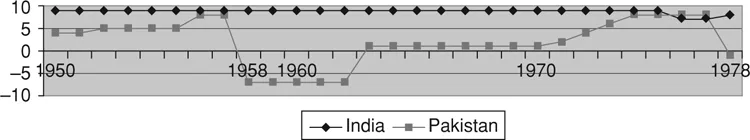

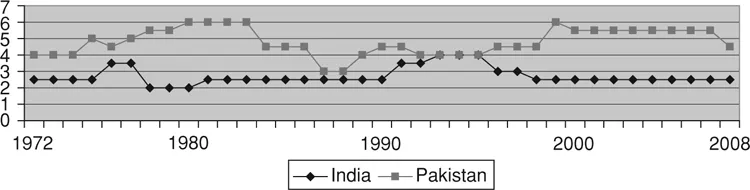

Conventional accounts, however, accept that there is a genuine and persisting regime difference between the two countries. Consider the graph we can generate from the Polity IV data for the first three decades of independence, and then the graphs of Freedom House data (Figures 1.1–3).

Freedom House labels India “free” from 1972 to 1974, from 1977 to 1989, and from 1998 to 2007 (and “partly free” in 1975–6, and from 1990 to 1997). Pakistan is judged to be “partly free” from 1972 to 1978 and from 1984 to 1998, and “not free” from 1979 to 1983 and from 1999 to 2007. Pakistan returned to “partly free” status in 2008 (see Figure 1.2). Alternately, the Freedom House data can be graphed to show the average “political rights”/ “civil liberties” score, where “1” represents the highest degree of freedom, and “7” the lowest (see Figure 1.3).2

The Freedom House sorting depends on scores on “political rights” and “civil liberties” that require democracy to be practiced in the country as a whole. In India, the demotion to “partly free” in the 1990–7 period was due to “methodological modifications,” but it is possible that the scores were reduced because of state repression of the Kashmir insurgency.3 In Pakistan’s case, the “partly free” designation in the 1984–98 period, during which elections were held, and freedom of press and assembly were quite

strong, was due to the power of the military to make and break elected governments, including those with a majority in parliament.4

Putting these countries – and the others Freedom House evaluates – into these categories is largely a matter of careful assessments of the intensity and spread of certain practices such as arbitrary police action. Changing a designation from “free” to “partly free” and to “not free” is done only with a great deal of deliberation by the Freedom House experts.5 For some purposes – sorting out the causal links between “democracy” and “development” for example (see Hadenius 1992) – it makes sense to develop an index of democratization, so that countries are scored as more or less democratic than others. More recent work, however, has tended to use dichotomized or trichotomized data (see, among others, Przeworski and Limongi 1997; Boix and Stokes 2003; D. L. Epstein et al. 2006; Hadenius and Teorell 2005).

Freedom House has provided a separate evaluation of the parts of Kashmir ruled by India (since 1998) and Pakistan (since 2002). Kashmir-in-Pakistan has been labeled “not free” for all the years through 2008; Kashmir-in-India “not free” from 1998 to 2001 and “partly free” from 2002 to 2008. That contrast would probably have described the two Kashmirs after 1947: Pakistan’s part “not free” throughout, and India’s mainly “partly free” or “not free” (and just possibly judged “free” in the period 1977 to 1983). Like Kashmir, much of India’s northeast has suffered almost since independence from a systematic denial of civil liberties in those states where the army has been a constant presence. As Vajpeyi (2009: 36) persuasively argues:

As she notes, “the rest of the country carries on as though it is possible to gloss over the reality of military rule as a temporary aberration and a mere enclave in what purports to be the world’s largest democracy” (Vajpeyi 2009: 38; see Human Rights Watch 2006 for details on Kashmir). Around 5 percent of India’s population lives in that enclave, no small number of people, who need to be kept in mind in the analysis that follows.

Defining democracy and autocracy

I have chosen here to draw some sort of a line between an autocracy and a democracy, on the basis of where sovereignty ultimately rests: with the people, or with self-appointed rulers. The definition of democracy that essentially requires that elections be free and fair and that no other power (such as the military) can veto decisions made by elected rulers suggests an either/or situation (see Schmitter and Karl 1991; for a succinct essay on conceptualization and measurement of “democracy,” see Berg-Schlosser 2007). Some situations would not be clear, in a country in which local political systems are undemocratic in some way (see Gibson 2005), or in which day-to-day politics consists of rulers who are not held accountable or who even flout the law. In my view, those countries are democracies if in a crisis it is the citizenry that remains sovereign. On the other hand, if a strong majority of the citizenry – leaving aside the question of precisely what proportion of the citizenry we are talking about, and how strong the feeling is – concedes the right to rule to a person or institution other than “the people,” we would have a “legitimate” autocracy.

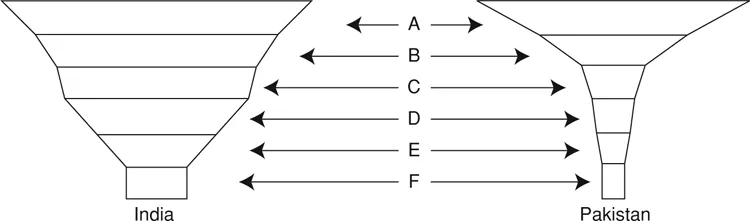

Some help in evaluating where India and Pakistan fit using these criteria is to be found in the State of Democracy in South Asia report (see also a summary article, deSouza et al. 2008). This report is based mainly on a very careful and convincing opinion survey, conducted in the five major countries of South Asia in 2004. The graph that depicts the “funnel of support for democracy in South Asia” (SDSA 2008: 13) shows a “stage one” bar indicating the percentage of respondents who support government by elected leaders. For India the figure is 95, and for Pakistan 83 (Figure 1.4). The “funnel” – perhaps “inverted pyramid” would be a better description – is then drawn by cutting away the base of that possibly superficial support for democracy, by showing five more bars underneath, each of which represents the bar above minus the respondents who have answered questions in a way that negates their support of democracy.

When those who “prefer dictatorship sometimes” or are indifferent between democracy and dictatorship are excluded, India’s bar shrinks to 73 percent, while Pakistan’s shrinks even more dramatically, to 45 percent. Excluding those who want army rule produces a 59 percent bar for India and a 19 percent bar for Pakistan. Excluding those who want rule by a king has less effect, understandably: 55 percent remain in the Indian inverted pyramid, 13 percent in Pakistan’s. Excluding those who want a strong leader without any democratic restraint gives India a bar representing 40 percent, and Pakistan

one representing 10 percent. The final cut excludes those who want the rule of experts rather than of politicians; here India’s bar is cut in half, to 19 percent, while...