eBook - ePub

Practicing Counseling and Psychotherapy

Insights from Trainees, Supervisors and Clients

This is a test

- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Practicing Counseling and Psychotherapy

Insights from Trainees, Supervisors and Clients

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Practicing Counseling and Psychotherapy: Insights From Trainees, Supervisors, and Clients offers a framework for understanding the counseling and psychotherapy process that can be used in any training program. Clinical examples and discussion questions are included throughout the book, and are based on a large-scale empirical study that qualitatively and quantitatively examines the experiences of trainees, clients, and supervisors. This volume is an excellent resource for those who want an insider's view and conceptualization from the perspectives of psychotherapy trainees, their clients, and their supervisors.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Practicing Counseling and Psychotherapy by Nicholas Ladany, Jessica A. Walker, Lia M. Pate-Carolan, Laurie Gray Evans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Journey to Becoming a Therapist

Two roads diverged in a wood and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

—Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken

Without a doubt, one of the most important jobs in the world is that of a therapist. Equally, without a doubt, one of the most difficult jobs in the world is that of a therapist. As a therapist, you are asked to emotionally invest yourself in others, spend years of study learning about interpersonal approaches to working with clients, engage in lifelong self-examination, and eventually settle with the knowledge that much of your work will not provide immediate results. All of this is done for, at best, a modest salary. So then why do it? Perhaps the best answer to this question is because of the love of the work and the knowledge that simply being with a person who is suffering can be healing and offer comfort. How many greater goods are there?

Our book is intended for those who are interested in learning the ins and outs of what it takes to become an effective therapist. We rely on our experiences that began when we were students up to the present time as educators and practitioners. We approach this work with an honest and frank assessment of the ups and downs we have experienced. We also depend on information from a large-scale study we conducted as a guide for offering real-life data from the mouths of trainees, their clients, and their supervisors. In essence, our goal is to offer a realistic, behind-the-scenes, and infront-of-the-scenes look at the training and practice process.

Some notes about terminology. Throughout the book we primarily use the term “therapy” as a synonym for words such as counseling and psychotherapy. The basic premise that underlies these terms is that psychological models, theory, and research inform practice. In some circles, these terms connote unfortunate turf battles between disciplines that have little grounding in real life situations. We have all known excellent master’s and doctoral-level counselors, clinical psychologists, counseling psychologists, social workers, and psychiatrists, just as we have all known their incompetent counterparts. Throughout our book we will talk about that which makes therapy effective and leave the turf battles for the professional organizations. To that end, we don’t limit ourselves to literature from only one discipline but, rather, incorporate the literature from all of the aforementioned disciplines, thereby hopefully offering a rich understanding of the work of therapy. Our hope is that trainees in each of the disciplines will find our book useful and bring therapists together for the common good of helping clients.

In a similar fashion, we are not convinced that operating from a singular theoretical approach is prudent (nor is it adequately supported by research). Although we do not eschew theory, we believe that working with clients involves a comfort with being informed by multiple theoretical perspectives. The Dodo Bird Verdict still seems to be true: “Everybody has won and all must have prizes” (Luborsky et al., 2002; Rosenzweig, 1936). We also agree with Bruce Wampold, who states in his meta-analytic review of treatment approaches in The Great Psychotherapy Debate, “The essence of therapy is embodied in the therapist” (Wampold, 2001, p. 202).

In addition, we prefer the term “client” to “patient.” Carl Rogers first used the term “client” to minimize or decrease the hierarchical implications around the term “patient.” The use of “client” also highlighted a more optimistic view of people’s ability to change and was therefore more empowering to the help-seeker. We, too, believe that “client” is a more humanistic (i.e., less dehumanizing) term to refer to those with whom we work. We also believe that using the term client keeps therapists in the mind-set of the collaborative nature of the therapeutic work, an element of successful therapy.

We mentioned previously that a study we conducted informs the chapters throughout our book. In order to understand the therapy training process we decided to undertake a large-scale research project examining the ins and outs of therapy and the training experience from the perspectives of everyone involved. We learned pretty quickly why no one had conducted such a naturalistic investigation (i.e., the undertaking just about sent us to the undertaker!). The official name of the study was the Psychotherapy and Supervision Research Project, but from this point forward we will simply refer to it as the Study.

Basically, the Study involved tracking four beginning therapists, their clients, and their supervisors for a little over a 2-year period. The basic structure of the Study was that we observed four therapists, each of whom worked with four to six clients, and each of whom worked with one or two supervisors. We videotaped and audiotaped all of the therapy and supervision sessions. We used quantitative measures at multiple points in time including pretreatment, presession, postsession, and posttreatment. We conducted qualitative interviews after every therapy session with both the trainees and their clients, and after every supervision session with both the trainees and their supervisors. In all, 4 trainees, 16 clients, and 6 supervisors were studied across more than 250 therapy and supervision sessions. A summary of the methodological protocol, as well as the quantitative and qualitative variables, can be found in Table 1 in the Appendix.

When applicable, we use data from the Study to illustrate concepts and ideas about therapy. In that way, the concepts are grounded in real-life examples. In our examples from the Study, we altered the demographic information about the volunteer participants to protect their anonymity. Although we do use actual data from the questionnaires the participants completed and the interview information they provided, we did not believe changes in the demographics compromised the integrity of the concepts we attempt to convey.

As can be anticipated, the data set was enormous but also quite rich. We were very pleased with the findings and use them to illustrate the practices we discuss. Although we provide examples of what worked well, we also provide examples for when things did not go well because learning takes place from our failures as well as our successes.

We thought the qualitative and quantitative results of the Study would be useful to illustrate concepts we discuss throughout the book. However, because there was so much data we thought it prudent to attend to the nuggets of data that were most illustrative to the topic at hand so that the text would not be too cumbersome with tables and figures and lose focus on the points we were attempting to illustrate. That said, we also realized that the data from the Study could prove useful to explore the topics more in depth that in turn could stimulate more reflection and further discussion (e.g., many types of secrets that therapists do not share with their clients). To that end, we have included the bulk of the results of the study in an Appendix, and encourage you to refer to it as desired.

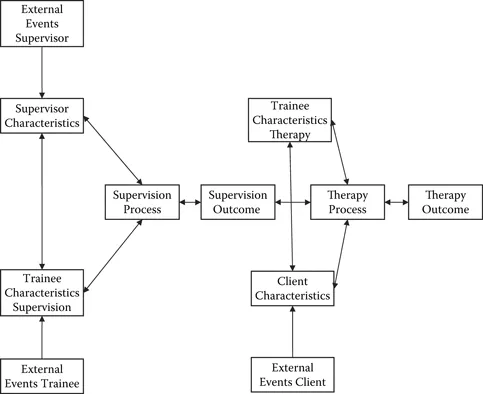

The overarching structure of the book is represented in Figure 1.1. In essence, we examine therapy process and outcome in relation to supervision process and outcome, all in the context of client, therapist, and supervisor characteristics and external-therapy events. To be sure, therapy process and therapy outcome are not clearly distinguishable. Like many constructs in the therapy field, they seem to be solid in the middle and a little a fuzzy on the outside. That said, generally speaking, therapy process can be seen as what happens in therapy sessions (e.g., therapist and client behaviors) whereas therapy outcome pertains to short and long-term changes in the client (e.g., decrease in depression) that result from therapy processes (Lambert & Hill, 1994). To be sure, there is overlap in what can be labeled a process variable from what can be labeled an outcome variable. However, the labeling system can prove useful as a heuristic manner of looking at psychotherapy. Supervision process and outcome can be similarly defined. For a more extensive appreciation for the primary therapy and supervision variables attended to in the book, please see Table 2 in the Appendix.

Figure 1.1 Categories of Therapy and Supervision Variables.

Each chapter takes a close look at a subset of these variables. To be sure, there are many other variables to be considered; however, we have found that these are the primary ones that you will run across as a therapy trainee. We begin by looking at therapy process variables and consider the essential skills used by therapists. In the next chapters, you will learn ways to conceptualize clients and conceptualize yourself as a therapist. You will then be provided with ways to conceptualize therapy outcome to the point of termination. Next, we attend to supervision variables related specifically to how you can get the most out of supervision. We bring it all together with Lydia’s Story, which is a narrative that captures the entire first training experience of “Lydia,” a beginning trainee. We conclude with a look at how to engage in therapist self-care and what we know leads one to become a master therapist.

At the end of each chapter, we include a set of exercises intended to be thought-provoking, stimulate self-reflection, and encourage debate among your peers. There is still a great deal unknown about how therapy works, and we contend that continuous examination of assumptions is a healthy enterprise. Indeed, self-awareness is a skill that is consistently practiced by the most accomplished therapists.

We use “we” throughout the book in reference to our group consensus about ideas that we all tend to believe. At times, we may get more personal, such as when we refer to a specific example from our training or our current professional work. In these cases, you will see one of our initials in parentheses following these statements (i.e., NL, JW, LPC, LG).

We have also set up a Web site for the book to answer your questions and hear your reactions to the things we say (http://www.routledgement-alhealth.com/ladany.com). We recognize that becoming a master therapist is a lifelong endeavor, and we want to hear about how you are doing along the way. It is also a place for others to share their experiences so we can all learn from one another. We look forward to hearing from you!

What Makes an Effective or Ineffective Therapist?

This question is perhaps the overriding query of the entire book. We boil down the answer into three key features that make for an effective therapist: empathy, managing countertransference, and the ability to tolerate ambiguity. Although on the surface, having only three things to learn seems rather simple. However, it is our belief that to adequately learn each of these skills takes years of practice and self-examination. It is also likely the case that most therapists never reach an adequate level of each of these skills, which may explain the variations found in therapeutic outcome. Although we will be discussing each of these skills more throughout the book, they are worth mentioning here to set the framework for our basic assumptions. First, in relation to empathy, or in essence, the ability to understand another person “as if” you are that other person, we believe it is vital for therapists to understand a client’s framework to be able to help them. It is not sufficient to sympathize, or feel sorry for the client. The essence of empathy is the notion that you yourself could be in that client’s shoes given the same life circumstances. The closer you can get to that belief, the more empathy you will have. The further from that understanding, the more blocked you likely are, and, by default, the more countertransference is operating.

In a nutshell, countertransference is how your biases as a therapist are interfering with your ability to empathize with a client. We all have countertransference, and as can be seen by the definition, we see countertransference as a pantheoretical construct. The key to managing countertransference is to first identify it (no longer allow it to be a blind spot) and second to work through the feelings associated with the biased belief (whether they originate from your past and/or the client’s behavior).

Finally, we believe that it is therapeutically beneficial to be sitting with a client and every now and then say to yourself, “I don’t know what the hell is going on right now.” Of course, as a beginning therapist, this thought may be entering your head more than every now and again. However, expert therapists have indicated that getting comfortable with, and tolerating, the inherent ambiguity of therapy allows for an openness of new ideas to enter the treatment, as well as ultimately assist in therapeutic outcome. Therapists who are the most dogmatic about an approach also tend to be the least open to alternative ways of thinking. As a result, this may stifle their ability to learn and help their clients. So the lesson here is to learn how to be comfortable with not knowing.

We began this chapter by noting that becoming a therapist is a noble thing to do. As with many noble adventures, the road is less traveled for a reason. In the end, though, we believe the adventure is worthwhile and we wish you the best in your journey!

Discussion Questions and Exercises

Discussion Questions

- What made you want to be a therapist?

- What setting do you eventually want to work in (e.g., Hospital? College counseling center? Community mental health center? Veteran Affairs? Prison system? Children and Youth advocacy?)? Why do you want to work in that setting?

- What are some of the chance events in your life that led you to the therapy profession?

- If you were not going to be a therapist, what occupation would you like to have? How can you keep aspects of these other occupational interests as part of your avocational life?

- What do you think will be your greatest challenge in this field?

- What do you think will be your greatest strength in this field?

Exercise: Professional Informational Interviewing

Career counselors will tell you the best way to learn about a profession is to interview people already in the field. To that end, your task is to interview a professional in a specific mental health occupation in which you are interested. Consider places in which you would like to work once you have graduated. Also, think about the types of clients, potential mentors, and so on. Use what resources you have to identify a person you would contact for an interview. Don’t be afraid of rejection. Most people love to have their ego stroked! If needed, you can do this interview on the phone. As a general structure for the interview, look at it as something that would last about 45 minutes. Some guidelines for what to focus on include the professional’s (a) experience entering the field (i.e., training, obstacles, chance happenings); (b) current tasks; (c) likes and dislikes of present job; and (d) match with expectations from when he or she was a graduate student. Rinse and repeat as desired!

CHAPTER 2

The Work in Therapy

All adventures, especially into new territory, are scary.

—Sally Ride

Do you feel ready to be doing therapy? Typically, when I (NL) ask my students this question, I receive a resounding “No!”

I counter, “But you have had multiple courses on theory and research. You have taken helping skills classes with great professors (most of the time!), and have received extensive training in what it means to be an ethical professional.”

Silence ensues along with a number of head drops. Then I am reminded how scary it can be to venture into new territory. I typically have to explain to my students that you never really feel ready to begin seeing clients. I’ve taught master’s and doctoral students in counselor education, counseling psychology, clinical psychology, social work, and psychiatric nursing at three universities and have rarely met students who say they are completely ready to see their first client. They can provide, though, numerous reasons for why they aren’t ready, and how much more training they need. In the end, it is important to embrace your nonreadiness. In fact, you are probably as ready as you’ll ever be. In reality, you were pro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Tables and Figures

- 1. The Journey to Becoming a Therapist

- 2. The Work in Therapy

- 3. Understanding Your Self as a Therapist

- 4. Conceptualizing and Understanding the Client

- 5. Therapy Outcome

- 6. Getting the Most Out of Supervision

- 7. Lydia’s Story

- 8. The Next Steps

- Appendix

- References

- About the Authors

- Subject Index

- Author Index