![]()

1

CONFLICT AND CRISIS NEGOTIATION

The negotiated resolution model

Gregory M. Vecchi

This opening chapter bridges the gap between theory and practice by presenting a model for the attainment of desired negotiated outcomes. The negotiated resolution model (NRM) works in all aspects of negotiation but it is especially effective in high-conflict (instrumental) situations such as barricaded hostage or kidnapping events, as well as in crisis (expressive) situations such as barricaded crisis, suicide and psychopathological-related events.The NRM proposes a method for attaining a specified negotiated outcome based on the assessment (initial and continuous) of the subject’s needs, conflict behavioural patterns and state of mind in order to determine the appropriate verbal skill sets to be employed. Embedded in the model is the continuous application of the Behavioral Influence Stairway Model (BISM:Van Hasselt et al. 2008), which is used to develop and maintain a relationship and credibility between the negotiator and the subject (individual in crisis/conflict) during problem-solving and crisis intervention processes, as well as dealing effectively with emotions during crisis intervention. Also embedded in the NRM are interaction manipulation techniques aimed at reframing the situation and influencing the perspective of the subject in order to obtain the desired outcomes of the negotiator. The chapter also focuses on when and how to use conflict and crisis negotiation techniques.

Negotiated resolution model

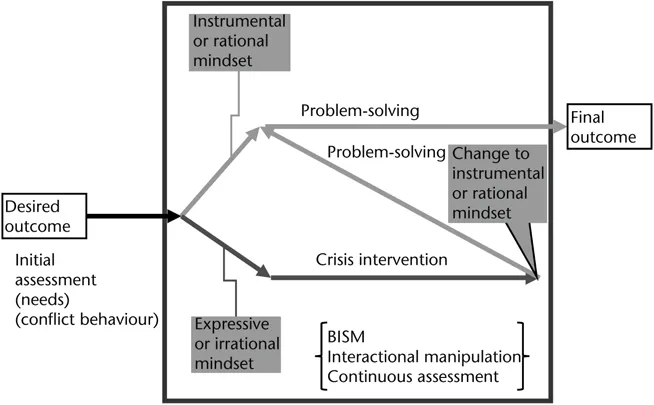

The NRM is a methodology by which to obtain desired negotiated outcomes through the assessment of the subject’s needs and conflict behavioural patterns in order to determine instrumental or expressive states of mind. Once the type of mindset is determined, the negotiator is then able to select the most effective verbal skill sets to bring about the desired outcome: problem-solving for instrumental behaviour or crisis intervention for expressive behaviour (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Negotiated resolution model

The NRM begins with the negotiator determining his or her desired outcome or end-game. For example, a law enforcement negotiator’s desired end-game may be the surrender of the offender, whereas an investigator’s desired end-game may be an admission or confession of guilt. In any event, it is critical to keep focused on the end-game throughout the negotiation even though it may be necessary to adjust it as a result of information obtained during the negotiation or because of circumstances outside the control of the negotiator. Once the negotiator determines the desired outcome, an initial assessment of the subject’s needs (i.e. desires, objectives, values, etc.) and conflict behaviour (accommodating, avoiding, collaborating, competing or compromising) are used to determine instrumental or expressive mindsets. If it is determined that the subject has an instrumental or rational mindset, the negotiator would use problem-solving or conflict negotiation techniques to obtain the desired outcome. On the contrary, if it is determined that the subject has an expressive or irrational mindset, the negotiator would use crisis intervention or crisis negotiation techniques aimed at bringing the subject to a more instrumental or rational state of mind, at which point the negotiator would initiate problem-solving techniques to arrive at the final outcome. Throughout the process, the negotiator uses the BISM to develop and maintain a relationship and credibility between the negotiator and the subject during problem-solving and crisis intervention, as well as dealing effectively with emotions during crisis intervention in furtherance of moving the subject to a rational mindset. Moreover, the negotiator also uses interactional manipulation techniques aimed at reframing the situation and influencing the perspective of the subject in furtherance of obtaining the negotiator’s desired outcomes. Throughout the negotiation process, continuous assessment is used by the negotiator to determine changes in mindset that signal adjustments regarding negotiation tactics in order to bring about the final outcome.

Determining outcomes

It is critical that the negotiator determine the desired outcome of the negotiation before interacting with the subject and keep the outcome in mind as the basis for the selection of the various strategies and tactics to be used during the negotiation. Ideally, the final outcome should match the desired outcome, such as surrender in a barricaded hostage situation or a confession during an interrogation; however, this may not be possible as a result of new information obtained during the negotiation, the behaviour of the subject or because of circumstances outside the control of the negotiator. For example, in 1999, Cuban prisoners took the warden and several correctional officers hostage at a correctional institution in St Martin Parish, Louisiana (Associated Press, 1999). The prisoners, who had finished their sentences, demanded that they be set free or they would kill the staff. As the negotiation progressed, it was determined that the prisoners had indeed completed their sentences but could not be released because they were Cuban citizens without legal status in the United States and Cuba refused to take them back. This situation resulted in them being in a ‘legal limbo’ which prevented their release into the United States or being deported abroad. Ultimately, a country agreed to take them, which resulted in the release of the hostages and their deportation out of the United States. In this example, the desired outcome of the negotiation was the release of the hostages without concessions; however, the final outcome had to be adjusted due to new information, legal considerations and decisions outside the control of the negotiators. Adjusted outcomes can also be based on the behaviour of the subject. For example, a commonly desired outcome of negotiation is the surrender of the offender without violence. This of course is dependent on the actions or inactions of the offender. If the offender kills a hostage on a deadline or if an individual who has symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia begins to shoot at police, then the desired outcome of no violence must be adjusted to a final outcome of deadly force. In this case, the negotiators might assist the tactical operators by persuading the offender to move near a window so the tactical team has the opportunity to use force via sniping, for example.

Assessing the subject

Assessing the subject involves evaluating his or her needs and conflict behavioural patterns. This step is critical to determining the mindset of the subject and choosing the most effective negotiation strategy and tactics for obtaining the negotiator’s desired outcome.

Subject needs assessment

People communicate for the purpose of satisfying needs, whether they are substantive or expressive (Vecchi, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2009a, 2009b). Conflict occurs when there is a perceived blocking of important goals, needs or interests of one person or group by another person or group (Wilmot and Hocker, 1998). When this occurs, people tend to respond with the intention to remove the block in order to satisfy the need. For example, in a child custody battle, the losing parent (whose need to have her children is blocked by her former husband via a court order) could respond constructively by taking her ex-husband back to court or destructively by taking her children by force. Depending on the action taken, the behaviour can be adaptive or maladaptive (Rosenbluh, 2001). For instance, the wife could take an adaptive approach by returning the children and seeking counselling, or she could take a maladaptive approach by taking the children hostage, barricading herself and threatening to kill them if she is not awarded custody. In both approaches, the wife is attempting to resolve her conflict; however, the manner used to resolve the conflict in order to satisfy the need is a function of the wife’s perception, previous experiences, level of resiliency and coping skills, which need to be accurately assessed by the negotiator.

Wilmot and Hocker (1998) see needs as falling into one of four general categories: (1) content, (2) relational, (3) identity and (4) process (CRIP). Content needs are external and tangible, such as food, money or transportation. These needs are fairly easy to ascertain because they are easily communicated by the subject to the negotiator. For example, robbing a bank in order to support a lavish lifestyle would be an example of a content need (money). Some common perceptions of conflict relating to content needs assessment include:

• People want different things.

• People want the same things.

• Perception of scarce resources.

Sometimes it is necessary for the negotiator to reframe these perceptions in a manner that makes the subject rethink his or her position, such as in the example of the orange (Vecchi, 2009a: 37).

Monica and Janice are roommates. In their refrigerator is one orange, which they both need. Both Monica and Janice state that they want the orange, and they refuse to split it, therefore either Monica or Janice will get the orange or no one will. On the surface, it appears that they want the same thing and there are not enough resources (oranges) to satisfy their needs; however, through further inquiry, the negotiator determines that Monica wants to eat the meat of the orange and Janice wants to use the peel of the orange to bake a cake. The situation can now be reframed and described as Monica and Janice wanting different things with sufficient resources rather than them wanting the same thing with scarce resources. This changes the perception of Monica and Janice from one of conflict to one of collaboration allowing for the needs of both parties to be satisfied: Monica gets to eat the fruit and Janice gets the peel for cooking.

Relational needs have to do with the way people treat each other with regard to respect and interdependence. Everyone has different expectations as to how they expect to be treated and these expectations differ based on social status and roles. For example, a person has different expectations with regard to interactions with their children versus parents versus peers versus supervisors, etc. If these expectations are not met, then negative feelings of disrespect and over-control will prevail (Vecchi, 2009a, 2009b).

Identity needs have to do with self-esteem issues with regard to saving face and protecting the self-image from the threat of feelings of humiliation, embarrassment, exclusion, unimportance and being demeaned. More importantly, identity needs translate directly to the need for physical and emotional security, recognition, control, dignity and accomplishment. These needs are the most personal of the CRIP needs, thus they are the hardest to disclose by the subject to the negotiator (Vecchi, 2009a, 2009b).

Process needs relate to the structure or forum of the dialogue such as the degree of creativity, participation and formal/informal and public/private contexts. Process needs are a matter of preference and are connected to personality. For example, in the case of a contested divorce, a married couple often has the option of choosing to resolve the divorce through court or mediation.1 If the couple each differed in their preferences regarding court and mediation (formal versus informal), then the person who did not obtain their preference would experience a conflict with regard to process needs (Vecchi, 2009a, 2009b).

It can be difficult for the negotiator to accurately assess CRIP needs, especially relational and identity needs, simply because these needs are often of a very personal nature and emotion-based and the subject will hide or not reveal these needs until he or she is comfortable and trusts the negotiator. In these cases the negotiator must listen carefully to the context of the situation in order to gauge the accuracy of the needs assessment. Some people may initially be hesitant to reveal conflict associated with relational and identity needs but, in the interest of cooperation, may instead reveal a content need that is in conflict, which is only a symptom of the problem. For example, in a divorce mediation, a wife complains that her spouse is a ‘bad husband’ because he does not make enough money for them to raise their son in the manner which he deserves (content need conflict). Based only on that information, the mediator suggests three options: (1) the husband could find another job; (2) the wife could get a job; or (3) they could remove their son from private school and buy his clothes at discount stores. All of these suggestions serve to increase the amount of money available to the family; however, it turns out that lack of money is only a symptom of a bigger problem. When examined further, it is determined that the husband never lets his wife have any say in the way their son is raised; he dictates what he wears, where he goes to school and what sports he plays, which makes her feel excluded and demeaned (identity need conflict), as well as disrespected and controlled (relational need conflict). This overlap of CRIP needs is common early on in a negotiation, especially when it relates to identity and relational needs conflict. Negotiators should be aware that conflict in the context of interpersonal relationships oftentimes has identity and relational needs at its core, even though the subject may indicate content and process needs as being the primary issue. In other words, content need conflict solutions rarely succeed in interpersonal disputes (Vecchi, 2009a, 2009b).

Subject conflict behaviour assessment

When a person’s needs, values, objectives, goals or desires are perceived to be blocked or delayed, conflict ensues, which causes certain behavioural tendencies or ...