CHAPTER 1.1

Reading Visuals

Visual literacy is a fluid term which can change depending on its context. In its natural home, the subject of Art, definition of the term predictably becomes a rather complex affair, purely because of the multitude of concepts and technical ideas that must be taken into consideration. When it comes to applying the term to Literacy, we must necessarily adjust our understanding of it to better fit the subject. In order to make our study of visual literacy both relevant and useful to the English curriculum, it is important to build our definition around existing literary and linguistic concepts. In other words, it must fit comfortably within the landscape of the present curriculum while at the same time adding something new and worthwhile.

As stated in the Introduction, the key term here is narrative. If we keep in mind that any visual literacy work in English should be linked to the act of storytelling and its attendant concepts such as character, plot, theme and tone, then we should not veer too far off course in our planning and teaching. This is not to say that the development of general visual literacy must always be linked to a recognisable narrative, of course, but in terms of Literacy studies, it is important that we anchor our work and skills to a base which will allow students to develop their English skills. A good example of this comes in the form of one of the activities featured in chapter 1.3. Herein, I suggest that a useful painting to study with children is Joseph Wright’s ‘An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump’. When examining this picture, even a cursory glance reveals a multitude of tantalising and enigmatic details: the child observing the fate of the bird, terrified yet fascinated; the young lovers, self-absorbed and uninterested in the demonstration; and the implacable gentleman, lost in thought. In short, the painting is the locus for a potentially limitless amount of stories and with a little imagination we can consider it in the same terms as we would any novel. For example: How could we describe the characters we see standing around the experiment? What are they feeling? What happened before and after this moment? What is the tone of the scene? How does it make us feel, and why? On the other hand, we would not be able to derive a narrative as easily from more abstract pieces of art such as Mark Rothko’s famous paintings, many of which are composed wholly of large blocks of colour.1 Allow me to clarify my point here (which is not in any way intended to be an argument against modern art): art experts would quite rightly argue that Rothko’s beautiful works do indeed transmit narratives, after all they undoubtedly have the power to inspire emotion and provoke strong feelings within us, yet these narratives (in the traditional sense) are unarguably more obscure than Wright’s. This is not, however, to say that we have to give in to the rather creatively bankrupt (not to mention boring) view that our work in visual literacy must solely be based around images which contain human beings with recognisable facial expressions. While Wright’s picture is a good example of a suitable resource, we could just as easily use a painting such as Henri Rousseau’s famous ‘Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!)’, that depicts a tiger prowling through the jungle illuminated by a flash of lightning. This work, despite lacking any images of people, nevertheless fulfils the criteria of a narrative image by possessing a clear plot (the tiger stalking through the jungle) and at least one character (the tiger himself) who displays emotion (a visible reaction to the tumultuous storm) – all of which are features that Rothko’s paintings, by their nature, do not possess. Indeed, analysis of works such as Rothko’s would be better served in the primary school by Art as a subject area, not Literacy.

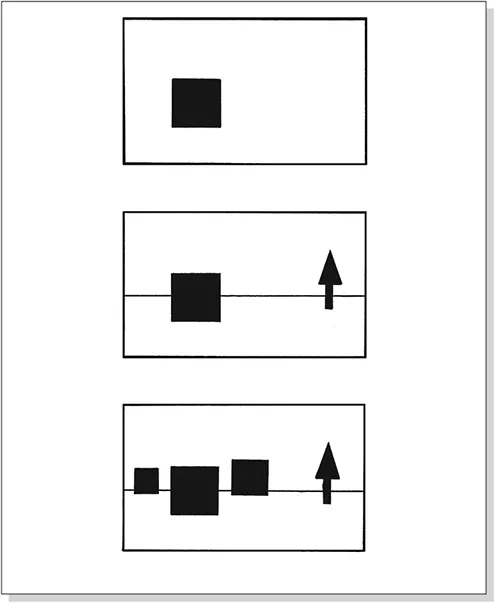

Yet whether or not we consider Rothko’s work too abstract to derive a useful narrative from, the question raised is an interesting one: at which point does an image stop being ‘just’ an image and take on a narrative dimension? Let us consider, for example, the three images in Figure 1.1. The top image is a large black square against a white background. This somewhat abstract image is difficult to reconcile with even a simple story. Admittedly it is not impossible (a close-up of an alien eye for example? A square hole that has suddenly opened in time and space?), but the image is somewhat self-contained in that any imaginative scope is ultimately limited by the sparseness of what we see. The middle image shows the same block but with two very simple additional elements: an object to the right of the square and a horizontal line running across the width of the picture. Immediately the image and our reading of it must readjust radically to incorporate the new information. By placing the square close to something else, we now have a sense of perspective and the square enters into a relationship with another object. For example, if we read the smaller object as a tree (I say ‘if’ purely because I wish to stress from an early stage that images, like written texts, should not always be limited to a single unequivocal meaning, especially abstract ones) then we have a sense that the square might be rather large. We might also raise questions about the location of the square (is it outside? Is it supposed to be there or has it just appeared?). If we then examine the bottom image, which shows the same image as the one above but with the addition of two other differently sized squares, a new relationship and narrative dimension is introduced into our analysis. Again, this is perhaps best expressed in the form of questions: Are we looking at a group of buildings? Why are the buildings different sizes? Is the bigger one more important than the smaller ones? Is it a family of strange beings? Even this relatively simple arrangement of lines and shapes has therefore prompted a number of potential stories or ideas. While all three of these relatively abstract images could inspire a story, the middle and bottom images are easier to read and attribute narrative qualities to than the top purely because the extra visual information imbues the image with a relational quality and provides a sense of context.

Therefore, while it is perfectly conceivable that we could develop students’ visual reading skills in Literacy to the point where they are able to give an insightful and mature reading of

highly abstract images such as Figure 1.1, we do in fact need to anchor our work to existing Literacy skills. This does not mean that we are merely re-presenting old teaching material in a new way. Ideally, any exploration of visual literacy should be situated in the context of our existing English work while allowing for the fact that integrating new media and concepts into our teaching will necessarily take us into some previously unexplored educational territory. It should help us to achieve a twofold objective: to explore dynamic new forms of literacy while simultaneously reinforcing and consolidating the skills we have always taught.

Defining visual literacy terms

As with any subject area, a definition of key terms and concepts is necessary to begin with. Admittedly, we are not working towards an unnecessarily complex or overly theoretical study of visual language with children here, but this is no reason not to introduce and clarify some of the more straightforward ideas. As with many of the terms encountered in academia, the more we search and the further we hunt for a definitive meaning, the faster we realise that singular definitions are almost impossible to locate. If we consider the term ‘icon’, for example, we are offered a plethora of subtly diverse meanings. A traditional definition of an icon is that it is ‘an image or statue … a painting or mosaic of a sacred person’, establishing the term firmly in a religious context (Oxford Reference Dictionary 1986: 408). However, its meaning has undoubtedly widened beyond these parameters over recent years, as acknowledged by a more recent definition of an icon as an ‘abstract or pictorial representation of ideas, objects and actions’ (Sassoon and Gaur 1997: 12). Scott McCloud agrees, stating that an icon is ‘any image used to represent a person, place, thing or idea’, but goes even further, subdividing icons into the more specific categories of symbols (‘the images we use to represent concepts, ideas and philosophies’), the icons of language and communication (such as letters, numbers and musical notation) and pictures (‘images designed to actually resemble their subjects’) (1994: 27). Therefore these concepts vary with each source and while the above definitions are excellent, we need to modify them if we are to understand these terms accurately and in a way which is appropriate to the material covered in this book.

I would offer a slightly different way in which to consider the concepts of image, icon and symbol. It is easier to consider ‘image’ as an umbrella term, meaning ‘the visual material which we are looking at’. In this sense, the number of items depicted is irrelevant, for example we could be looking at a drawing of hundreds of people, yet we would still apply the singular term ‘image’ to it. The idea of a ‘frame’ helps to clarify this. Whether an image has a literal frame (such as a traditional painting in a gallery) or a figurative one (such as a photograph, which has no physical frame to speak of but does have boundaries or edges which the image cannot cross), we can usually define an image as anything we see within a given frame. As these examples suggest, image is also a cross-media term. Any two-dimensional photograph, painting, sketch or even mark on a page can be considered an image and in terms of film and television (commonly referred to as the moving image) an image would be what we see when the film or television programme is paused. Therefore ‘image’ is used here as a general term but certain images (or elements within an image) can be described by the specific terms ‘icon’ and ‘symbol’. An icon is a two-dimensional representation (drawn, painted or printed) of something tangible, such as a dog or a house, or even something intangible such as fear or thoughts. An important point to note here is that icons are indeed representations of real life. This is not simply a pedantic semantic point but rather a key idea which we need to establish early on in our study of visual literacy: an icon is, by its very definition, a depiction of something and not the object itself. As McCloud asserts, a drawing of flowers is ‘not flowers’, just as a drawing of a face is, in actuality, ‘not a face’ (1994: 26). Of course, the concept of icons can only correctly be used in terms of painted, printed or drawn images – images which are interpretations of reality. You would not, for example, look at a photograph of your friends and say that the people shown in it were icons, because even though the picture is undoubtedly only a representation of reality, the camera has in fact simply exposed light and has not offered an artistic interpretation of the subjects.

The third term to define here is ‘symbol’. A symbol is a specific type of icon which represents more than just an object or idea. Here we can turn to literary studies to aid our understanding. In their analysis of poetry and its elements, John Peck and Martin Coyle identify a symbol as ‘an object which stands for something else … [or] signifies something beyond itself’ (2002: 77). We can apply this idea to the visual image when we acknowledge that some icons are in fact symbols. Certainly, all icons are not symbols – it is the context of the image which determines this. An example will help here: if we see a painted image of a person holding a skull, the person is an icon (a representation of a human being) as indeed is the skull itself. Yet the skull is also more than just an icon, it could arguably be interpreted or ‘read’ as a symbol of death and could even provoke the viewer to reflect on the concept of mortality. If, however, we saw an identical skull connected to a human skeleton as part of an annotated illustration in a textbook, the context would demand we view the skull as nothing more than an icon. As with any piece of literature or work of art, we should beware of over-reading and try to avoid looking for a coded, deeper significance in every single aspect of it.

If we return to Figure 1.1, we can analyse it using these terms (but note that the following reading is pitched at an adult’s level, not a child’s). The bottom panel is an image which contains several drawn icons: a horizontal line, a large black square, two smaller black squares and another icon which we might view as being an interpretation of a tree (but is not necessarily one). As stated earlier, we should not assume that every icon is necessarily a symbol, so we let the context of the image guide us when looking for a deeper meaning than that depicted. The image is relatively abstract and is certainly not an information-based image such as a diagram or a map, so we could potentially interpret some of the icons symbolically. One reading, for example, might be that the ‘tree’ icon is symbolic of nature, while the blocks (due to their regular, geometric lines) could symbolise industry or civilisation, producing a reading of the image which explores the unnatural effect of human population on the natural environment.

The image–symbol–icon model is only a suggested approach, which will hopefully simplify any reading of images while at the same time showing that there is specific and appropriate terminology that can be used. It is not completely without disadvantages however. It is perhaps a little too complex for much younger children, for instance, and it is not always easy to classify something as a single image using the frame idea (if, for example, we were looking at several paintings on a cave wall, how would we tell if we were looking at one image or many?). Yet it does serve as an introduction to a vast and complex subject area and even if we do not introduce children to these terms immediately it will help to clarify the approach before teaching it. In addition, viewing visual material as icons and symbols reinforces the basic tenets of visual literacy, reminding us that we are in fact looking at representations and interpretations of things, not the things themselves, and that these icons may often possess a deeper, less obvious meaning if we consider them carefully.

Visual literacy and drama

Some of the activities contained in this book are drama exercises and this has been done for two reasons. First, this book intends to offer fresh perspectives on Literacy work and includes differing modes of assessment that, at times, move away from the traditional emphasis on written work. Second, from personal experience as a drama practitioner, I feel that no exploration of visual narrative is complete without establishing strong links with performance and movement and developing children’s drama skills. Activities which explore body language and facial expression are not only enjoyable for children, they also help them to gain a practical understanding of how we can read emotions and character through purely visual means. This is particularly useful in relation to the study of comics, picture books and film and television, as we cannot expect children to read a range of often complex emotions through visual cues such as facial expressions if they have not had any experience of doing it themselves. Drama, therefore, offers a safe environment in which students can explore a range of feelings and attitudes and witness how they can be expressed in more subtle, non-verbal and non-written ways. Moving beyond the individual, drama also provides the opportunity to examine how characters interact with one another and to learn how gesture and posture can be decoded to give insight into relationships. As the later chapters show, even very straightforward Drama sessions will enable us to explore theories of stage dynamics (how the positioning and movement of the actors’ bodies reflect the social relationships and power hierarchy between the characters). An understanding of dynamics is an essential part of being visually literate and is a way in which we can pick up on the nuances of the relationships between characters. It stems from a realisation that, as Mick Wallis and Simon Shepherd put it, ‘a stage group can be organised, not merely mechanically but also into relationships of power and energy’ (2002: 105). A nice example of dynamics can be seen in the film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007). In one of the film’s storylines, the malicious Dolores Umbridge (played perfectly by Imelda Staunton) has been sent to Hogwarts School by the Ministry of Magic as an Inspector. She relishes her newfound role and the authority it brings and this naturally creates conflict between her and the existing power base in the school. In one beautifully acted scene, the Deputy Headmistress Minerva McGonagall (Maggie Smith) confronts Umbridge about the cruel punishments she has meted out to students. The scene takes place on a staircase in the castle and begins with McGonagall’s polite but firm statement: ‘I am merely requesting that when it comes to my students, you conform to the prescribed disciplinary practices.’ At this point, the two women have stopped halfway up the staircase on the same step and are facing one another. As Umbridge counters the request and attempts to assert her power, she moves up a step on the staircase but McGonagall swiftly does the same so that they are again equal. When Umbridge cites the Ministry of Magic and the power of the law however, warning McGonagall that ‘To question my practices is to question the Ministry and, by extension, the Minister himself’, the affronted and shocked Deputy Head takes a step back down the staircase. Her retreat is immediately exploited by the Inspector, who takes another step up the staircase to proclaim to the assembled onlookers that ‘Things at Hogwarts are far worse than I feared. Cornelius [Fudge, the Minister for Magic] will want to take immediate action!’ What the scene does here is to cleverly articulate in a visual manner a quite complex power struggle between two women. While McGonagall is used to having a position which is almost at the top of the school’s hierarchy, she now has to readjust to the intervention of an individual who is imbued with an authority which comes from outside the institution. The women’s ascent and descent of the steps works on two levels: first it is, at least initially, a gently humorous sight gag (especially when we consider the difference in height between the two women); second, it is in fact an extremely effective way of transmitting detailed information about the power structure at Hogwarts and the characters of Umbridge and McGonagall. The jostling for position and superiority on the staircase is literal and metaphorical and, in terms of the adaptation process, condenses Umbridge’s rise to power (which in the novel J.K. Rowling excellently details over several hundred pages) into a few minutes of screen time. Children can, of course, be taught to look for such things in visual texts, but if we allow them to actually participate in activities which require them to express emotion and narrative through their bodies and faces, they will better understand how to interpret what they see in books, comics and films. Drama work therefore naturally feeds in to the study of visual media to help children read both static and moving images at a more sophisticated level.

Look closer: Where the Wild Things Are

Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are is an undisputed classic of the picture book medium. In the forty-five years since its publication, the book has undoubtedly proven to be timeless, remaining consistently popular with generations of children and adults and having recently been adapted for the big screen by acclaimed filmmaker Spike Jonze. Through pictures and minimal written text, the book tells the story of a young boy named Max who, dressed in a wolf outfit, is so naughty that he is sent to bed without any supper. Once confined to his bedroom, we see it transform into a forest, the walls fading away as the bedposts turn into trees and the carpet becomes grass. Max then gets into ‘a private boat’ and sails to ‘the place where the wild things are’ (Sendak 2000: 14–17), a jungle inhabited by giant creatures who make him their king. Sendak has made no secret of the fact that the book was heavily criticised by adults upon release and deemed too scary for children (Ludden 2005); however, it ultimately proved to b...