The city and the text

Remembering Dublin in Ulysses: remembering Ulysses in Dublin

Hugh Campbell

In Ulysses, James Joyce remembers Dublin. It is such a simple point that it is easy to forget. Not only is Ulysses an extraordinarily detailed portrait of Dublin life, it is one created at a physical and temporal distance. The final words of the novel are actually ‘Trieste—Zurich—Paris’, reflecting the fact that Joyce had barely set foot in Dublin during the seven years the novel took to write. Not only that, but by the time Ulysses was published in 1922, the Irish capital had undergone radical political, social and physical change: it was now the capital of an independent nation, but a capital that had suffered large-scale destruction during the 1916 rising and the war of independence. Right from the outset, Ulysses was, among many other things, an act of commemoration. Joyce’s famous boast, that if Dublin were destroyed it could be rebuilt entirely by reference to the pages of his novel, was really about recognising that the version he had constructed might in fact prove to be more enduring than the real city on which it was based. Joyce consulted street directories and maps, asked friends to send him all the shop names on particular streets, went to great lengths to ensure that his rendering of Dublin, 16 June 1904 was as complete and accurate as possible. ‘In Ulysses’, he said, ‘I wanted to stick close to the facts’.1

But if Joyce spent his entire writing life remembering Dublin, how does his native city choose to remember him? Initially, it seemed far more inclined to forget him. Ulysses was banned in Ireland, as it was in America, and Joyce’s exile remained in force long after his death in 1939. The opening of the James Joyce Museum in the Martello Tower in Sandycove, in which the first chapter of Ulysses is set, was really the first attempt to bring Joyce home. The intermingling of Joyce’s life, his fiction and the real space of the city that the tower exemplifies, continues through more recent initiatives such as the James Joyce Centre on North Great George’s Street—close to the Eccles Street address of the Blooms—and the annual celebrations of Bloomsday, with its uneasy mixture of pantomime and scholarly discussion. While the recent statue of Joyce on North Earl Street, off O’Connell Street, serves to announce very directly his acceptance into the pantheon of Irish greats and his newfound centrality to Dublin’s cultural tourism, the two projects of commemoration on which this chapter will focus are about something at once more direct and more difficult—the reintroduction of the text into the city from which it derives and which it depicts. It is straightforward enough to establish a museum or a study centre in a writer’s name, or to erect a statue of them in their native city, but to try to commemorate a work of fiction in its real setting is a much more slippery enterprise.

The first of these projects dates from 1988, the year when, somewhat spuriously, Dublin celebrated its millennium. The sculptor Robin Buick and the curator of the Joyce Museum, Robert Nicholson (also the author of a book on Joyce), inserted into the pavements of the city a series of 14 plaques tracing Leopold Bloom’s movements through the centre of Dublin in the eighth chapter of Ulysses, Lestrygonians. Nicholson explains the logic behind choosing this chapter:

The action of Ulysses takes place all over the city and in Sandycove, Dalkey, Sandymount and Glasnevin, so I felt that it would be more cohesive to concentrate on a single episode in the way that the plaques would fall into sequence as a trail. Few of the episodes actually conform to the public perception of Bloom walking steadily through the streets of Dublin, but one of them is admirably suited to this purpose—‘Laestrygonians’, the eighth episode, which describes Bloom’s lunchtime journey from O’Connell Street to the National Museum with a stop at Davy Byrne’s en route.2

Lestrygonians (each of the chapters in Ulysses was originally named after an episode in Homer’s Odyssey, although these names do not appear in the published novel) is also the chapter that gives us the fullest and most continuous access to Bloom’s consciousness. We are in Bloom’s head almost all the time as he moves through the heart of lunchtime Dublin. However, at regular intervals, Joyce slips back to a third-person narration and advances Bloom a little further along his route (it is a technique he calls ‘peristaltic prose’, equating his reports on Bloom’s progress with the regular swallowing motions of our digestion). It is these intermittent ‘stage directions’ that, almost exclusively, provide the material for the plaques. Here is Nicholson again:

The sequence of landmarks along the way is so closely described that Bloom’s position can be pinpointed to within a few yards at any point of the chapter. An added bonus is that most of the landmarks mentioned are still there. Since the opening of the chapter catches Mr Bloom in mid-stride outside Graham Lemon’s, I felt that we could place the first plaque at the starting-point of his journey outside the Evening Telegraph office in Abbey Street at the end of the previous chapter. The sequence then evolved easily enough with plaques spaced out at fairly regular intervals. Preference was given to important points in Bloom’s journey or to the opportunity to use a colourful quotation, but we were also mindful not to bunch up plaques in some places and leave overlong gaps in others.3

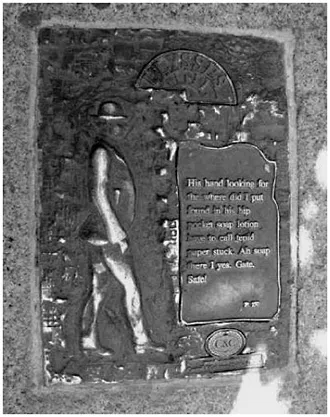

The bronze plaques, each about A3 in size, feature, in shallow relief, a bowler-hatted Bloom and a brief framed quotation. They are small enough to be inconspicuous, and sometimes you have to make a real effort to find them. A leaflet giving their locations and a short commentary by Nicholson was originally available but is long since out of print. In fact, at least one of the plaques has now disappeared (given that Dublin’s pavements seem to be dug up, patched and resurfaced on the slightest pretext, it is actually surprising how many of the plaques have survived), but it is still possible to follow the trail.

Robin Buick, Joyce Plaque on Westmoreland Street, ‘Mr. Bloom smiled O rocks at two windows of the ballast office.’

Robin Buick, Joyce Plaque on Grafton Street, ‘He passed, dallying, the windows of Brown Thomas, silk mercers.’

Following the sequence of plaques, it is striking that the final one, marking the moment where we leave Bloom to gaze at the nude statues in the National Museum, is the only one that really allows us to inhabit his mind (the quotation reads: ‘His hand looking for the where did I put found in his hip pocket soap lotion have to call tepid paper stuck. Ah soap there I yes. Gate. Safe!’).4

However, the second project I want to discuss chooses to dwell entirely in a character’s consciousness. This time, the character is Molly Bloom, Leopold’s wife. In the final chapter of Ulysses—Penelope—Molly lies in bed in the small hours, having been woken by Leopold’s slipping into bed (even though he tries not to disturb her by lying head to toe), thinking about lovers past and present. Her late-night reverie is presented as an unbroken stream of thought (the entire chapter is made up of only eight sentences), ending with a reaffirmation of her attachment to Leopold (the famous last words of the novel: ‘and Yes I said yes I will yes’).

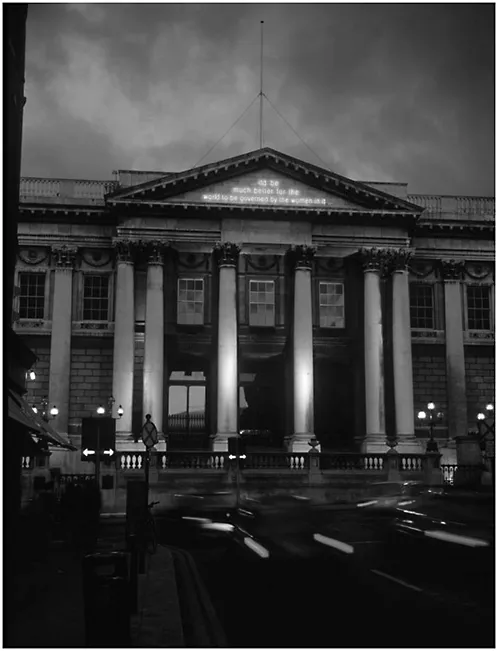

The chapter formed the basis of a public art project conceived and realised by Frances Hegarty and Andrew Stones in 1997. The artists placed nine fragments of Molly’s thoughts, rendered in cerise-pink neon, at a series of locations around the city. The fragmentary quotations focus on what they call Molly’s ‘humorous and ironic appraisal of the activities of men’.5 The locations are then chosen for their correspondences with the content of the quotations. Sometimes these correspondences are simple—‘… O that awful deepdown torrent O … and the sea the sea crimson sometimes like fire …’ is strung along the quay wall close to the level of the Liffey river. Often they are humorous—‘I hate an unlucky man’ is written above a bookmakers; ‘I wouldn’t give a snap of my two fingers for all their learning’ is found on the side of Trinity College. But they are never direct: that is, they do not highlight specific references to the city’s detailed geography in the way that the plaques do. The setting of Penelope is a bedroom in Eccles Street, but the artists have relocated this private reverie to the public space of the city. They use the text in a very different way to Nicholson and Buick, looking for thematic rather than geographic content. Their medium is also very different. Although neon signs are as much part of the urban furniture as the metal plates and covers embedded in the streets and footpaths, they are essentially nocturnal. For the duration of the project, the neon texts remained lit continuously. Although they retained a faint, constant presence in the daylight and noise of a busy city, it was only at night, as the streets faded into darkness, that they grew more intensely visible. Furthermore, and unlike the plaques, there is no intended sequence to these neon interventions (although there is a map showing their locations). You are supposed to stumble on them unexpectedly, to wonder at their provenance and meaning.

Robin Buick, Joyce Plaque on Kildare Street, ‘His hand looking for the where did I put found in his hip pocket soap lotion have to call tepid paper stuck. Ah soap there I yes. Gate. Safe!’

For Dublin, site-specific installation with neon, © Hegarty & Stones, 1997, ‘… it’d be much better for the world to be governed by the women in it …’

For Dublin, site-specific installation with neon, © Hegarty & Stones, 1997, ‘… O that awful deepdown torrent O … and the sea the sea crimson sometimes like fire…’

Of course there are all sorts of comparisons that could be made between the two projects, but for the purposes of this chapter I want to focus on the ways in which they reflect on the nature of memory and consciousness and their relation to the fabric of the city.

It is through the act of writing that Joyce remembers. Memory, for him, is something produced rather than received; it is active not passive, protean rather than unchanging. Henri Bergson, whose work Joyce knew, used the image of the search to explain memory, believing that, in the words of Edward Casey, ‘memory involves the creative transformation of experience rather than its internalised reduplication in images or traces construed as copies’.6 This is certainly true of Joyce, who completely revised his own attitude to his native city through the process of writing about it, but it is equally true of his chief protagonists of Ulysses—Stephen Daedalus, Leopold and Molly Bloom—who spend so much of the novel in dialogue with their memories. It is because memory plays such a major role in our consciousness that Joyce is able to sketch out the characters’ entire histories, despite the fact that we are in their company so briefly. He recognises that to know someone’s autobiography, you would only have to inhabit their thoughts for a single day of their life. In The Feeling of What Happens, the neurologist Antonio Damasio presents a model of the self in which overlaid on our core consciousness is a continuously evolving ‘autobiographical consciousness’.7 At any moment, it is this cumulative self which is present—a self made up more of remembered experience than of immediate sensation. This seems very close to Bergson’s concept of durée—usually translated as duration:

Duration is the continuous progress of the past which gnaws into the future and which swells as it advances. And as the past grows without ceasing, so also there is no limit to its preservation. Memory, as we have tried to prove, is not a faculty of putting away recollections in a drawer, or of inscribing them in a register … In reality, the past is preserved by itself, automatically. In its entirety, probably, it follows us at every instant; all that we have felt, thought and willed from our earliest infancy is there, leaning over the present which is about to join it, pressing against the portals of consciousness that would fain leave it outside.8

So the past is a constant, and constantly evolving, presence, ‘pressing against the portals of consciousness’. It does not need to be consciously summoned up. Shiv Kumar makes a distinction here between Joyce’s understanding of the functioning of memory and Marcel Proust’s: