- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ways Around Modernism

About this book

Stephen Bann examines the arguments for the centrality of French modernist painting. He begins by focusing particularly on the notion of the modernist break, as it has been interpreted with regard to painters like Manet and Ingres. He argues that 'curiosity', with its origins in the seventeenth-century world-view can be a valid concept for understanding some aspects of contemporary art that contest the modern, suggesting ways of sidetracking the modern by adopting a lengthier historical view.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art General1. Strange Encounters

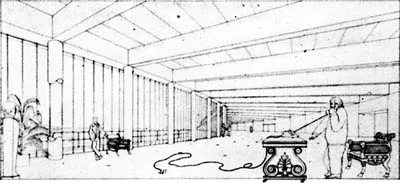

When and where did Postmodernism begin? I want to start by acknowledging the relevance to this question of an area of the arts that has a good claim to have launched the first debate about the era of the postmodern, and to have offered an exemplary way of understanding what was entailed in the shift from Modernism. At a recent exhibition of plans and drawings by contemporary architects from the collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montréal, my attention was taken by an elegant line drawing credited to the architect Léon Krier (Figure 1.1). This was tantalizingly captioned with a set of queries by the architectural commentator Colin Rowe:

So exactly when did [James] Stirling buy his first piece by Tomas Hope which quickly became so celebrated by the Leon Krier perspective for the Olivetti interior at Milton Keynes? Was it '69 or '70? This was surely a watershed.

Rowe's rhetorical question is addressed, we may conclude, primarily to the architectural cognoscenti. It takes for granted that

Figure 1.1 Leon Krier, draftsman, and James Stirling and Michael Wilford, architects, interior perspective for Olivetti Headquarters, Milton Keynes (1969–1970). Collection Centre Canadien d'architecture / Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal.

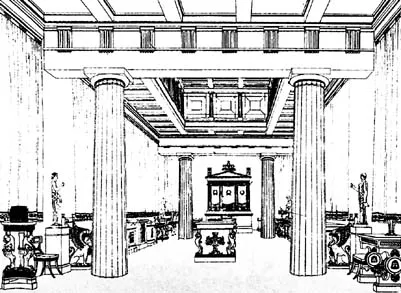

they are already aware of the mythic occasion when a specimen of the neoclassical furniture of the early nineteenth-century connoisseur and designer Tomas Hope, which had been bought by the well-known contemporary architect James Stirling, was then incorporated wholesale in an otherwise seamless modernist design, the Olivetti headquarters for Milton Keynes. Te drawing by Krier (who was at that point working in Stirling's office) shows the modern office building in a receding perspective, unexpectedly tenanted by two elegant armchairs, a classical herm, and a table that would not have been out of place in the line engravings published to accompany Hope's “classic style book of the Regency period,” first published in 1807 (Figure 1.2).1 Rowe's comment celebrates the visual encounter between the contemporary interior

Figure 1.2 Interior perspective from Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (Bolt-Court, UK: Longman, Hurst & Orme, 1807).

and the apparently ill-matched furnishings, and indicates that in this juxtaposition, precisely, is to be found the “watershed.” He calls attention to the point in time when such a mismatch was not regarded as a mistake or an anomaly, but accepted as a testimony to a wholly new conception of contemporary style—as a premonition of what would shortly be termed “Postmodernism.”

It is interesting to observe the precise terms in which Rowe's retrospective judgement has been couched. Te “event” in question is so exceptional that it cries out to be tethered down to a particular year. “Was it '69 or '70?” Tat the difference should matter is partly a question of squaring the relationship between Krier and Stirling, on the one hand, and other claimants for primacy in advancing the theory of Postmodernism, such as the architect Roberto Venturi, who published his Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture in 1966. But, on a more fundamental level, it is surely a symptom of the need to enhance the mythical moment by anchoring it within a lived history. No doubt, the planned Olivetti HQ was never destined to be filled with furniture in the style of Hope—though Stirling certainly shocked many modern purists with the classicizing rotunda that he installed at the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart in 1984.2 However, Krier's image gives just sufficient grounding in reality to the project for us to imagine that abrupt intrusion of the historicizing pieces of furniture. In the ghostly form of the line drawing, they have so strangely violated the functional world of the bulky receptionist, and interrupted the blandly receding perspective of the modernist interior.

Lunch on the Grass

We might say that the emphasis that is still placed upon the shock value of Manet's Déjeuner sur l'herbe (Lunch on the grass) (Figure 1.3) can be compared with this recent example. However, it remains essentially different. Manet's much-reproduced painting is, of course, infinitely more securely grounded in time and space than the architectural drawing

Figure 1.3 Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863). Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

that Colin Rowe hesitated to place in one year or the succeeding one. There can be no doubt at all about the place and date of its first public showing in Paris, which was at the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Nor does the work require us to make the imaginative leap of reconstruction that Krier's architectural sketch invites us to perform. This is a painting, and we can easily take a trip to view it in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, or see the reduced version in the Courtauld Institute Gallery in London.

However, the differences may not perhaps be so absolute as would appear at first sight. Can we in fact recover the full sense of what it was that would have seemed so out of the ordinary— to the point of being a “watershed”—in the first appearance of Manet's painting at that particular date? Michael Fried appears to put that issue directly on the line, when he writes in the last couplet of a poem dedicated to T. J. Clark, and also entitled “Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe,”

When at the age of eighteen I first stood staring and breathless in the Jeu de Paume

what most astounded me was that the paint appeared still wet.

In this text, let us bear in mind, Fried is speaking as a poet who is imaginatively reliving his own earlier life, and not as an art historian. He is reconnecting with his own vivid memory, and allowing that memory to resonate, perhaps, with the mythic moment when Manet's contemporary audience might have been similarly startled. But he has no intention of persuading us that the shock produced by the Déjeuner sur l'herbe, at the time of its first showing, would also have been registered by the Parisian viewers in terms of the canvas “appearing] still wet.” Maybe that would have been a banal impression at a nineteenth-century viewing, since the first sight of such works would usually have been at the vernissage, or varnishing day, when the artists were wont to apply their finishing touches. Contemporary critical evidence does not record that people were shocked by the painting for this particular reason, or indeed tried to translate their experience into verbal expressions congruent with such an impression.

As a historian, Fried knows this well—hence his concern in his historical study of Manet's Modernism to demonstrate that the radical nature of the painter's work can be defined in another, less context-bound manner. It resides in an aesthetic property that can be closely correlated with the observations of a few, especially perceptive contemporary critics. But in order to be appreciated fully, it must also be appreciated in the light of the broader developments in nineteenth-century painting to which Manet and a number of contemporaries were heirs. So Fried as a historian gives himself the task of endeavoring to trace—through a century of formal development—the practical application of a concept that he terms “facingness.”3 This concept, in particular, needs to be taken into account in determining why the painting of Déjeuner sur l'herbe was so crucial to the achievement of “Manet's Modernism.” In his poem, Fried comments quite elliptically on this point,

It was a moment in the history of the art of painting

when the weight of the broken water rushing out to sea exactly

counter-balanced the force of the waves rushing in.4

Such a powerful image as this could imply a critical revision of the concept of the “watershed,” as it was used by Colin Rowe. For a “watershed” is a familiar term denoting in the strict sense “a narrow elevated tract of ground between two drainage areas” (OED) that is instrumental in feeding streams and rivers on either side of the eminence. Te original term, which was evidently borrowed from an analogous German usage around 1800, has entered common parlance in the sense of a line or division between two systems of culture and thought. In this respect, it tacitly takes for granted the traditional equation between a high viewpoint and extensive knowledge of a field (considered metaphorically) that was prevalent in Western thinking about landscape from the early modern period onwards.5

Yet the lesson of Nietzsche's ladder should again be applied here. Te observer who is perched perilously high is not necessarily best placed to see into the future. Fried's powerful image of “counter-balanc[ing]” waters, on the other hand, evokes the collision of mighty currents in a turbulent sea. From the observer's point of view, the surprise is that the force of the incoming waves is “exactly” matched by that of the undertow, which pulls the “broken water” in the reverse direction. Instead of an even distribution of supply—extending towards the future and the past— we have a kind of maelstrom in which conflicting currents meet and part in different directions. But the burden of this surprising image is that the painting is held to have arrested these conflicting movements, and fixed them in a kind of dynamic stasis.

Particularities of verbal figuration—poetic expressions that seek to describe the effect of paintings—are not to be disregarded when we try to make sense of the history of art. This watery simile is, surely especially apt in the case of Manet's Déjeuner sur l'herbe. We talk rather loosely about finding the “sources” for paintings, as though they were waterways that derived from distant springs. No one today disputes that one of these faraway outlets that found its way into Manet's painting was the Renaissance artist Marcantonio Raimondi's print after Raphael's now lost Judgement of Paris. Te relationship might well have been noticed by the more artistically literate members of his audience, but it was not formally spelled out in writing until an article on the subject was published in 1908. An alternative source springing from the Concert champêtre in the Louvre (at the time attributed to Giorgione) was more openly avowed by Manet, according to his chronicler Antonin Proust, who specifically described his friend as intending to create a modern Giorgione.6

But these far-removed, so to speak, deep sources should not necessarily be privileged over the shimmering crosscurrents that animate the surface. While discussing the German art historian Aby Warburg's enga...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Preface

- Introduction by Margaret MacNamidhe

- Ways Around Modernism

- 1. Strange Encounters

- 2. Curiouser and Curiouser

- Seminar

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ways Around Modernism by Stephen Bann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.