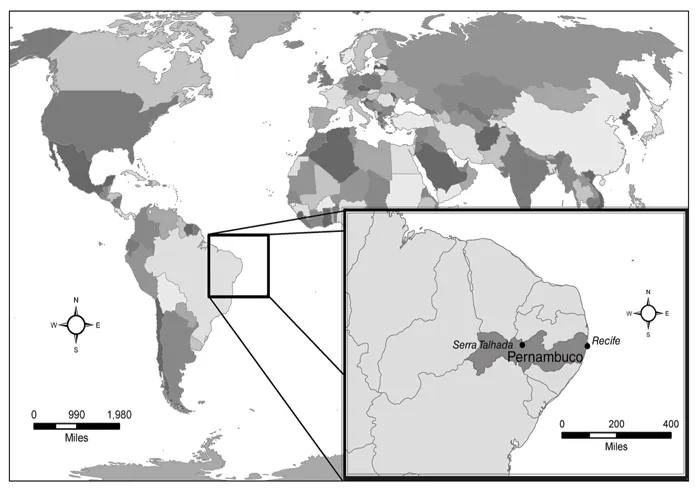

Yet, despite its seeming isolation and supposed stagnation, there are signs that the sertão—and the women who live there—are, in fact, deeply embedded in global flows. In 1995, in the early stages of fieldwork, I found myself at a workshop organized by a rural women’s movement in the remote town of Serra Talhada, named after the rocky outcroppings carved out of the landscape that loom nearby. The women had invited some male colleagues from the agricultural unions in the area to join them in studying and discussing an unfamiliar concept: gender relations. As a pitiless afternoon sun seared the tile roof of the borrowed union hall, some thirty-odd participants sat at rickety student desks, clustered in small groups around the meeting room. The walls were covered with butcher paper, filled with lists of terms describing rural men—“vain,” “hard-working,” “jealous,” “affectionate”—and women—“courageous,” “pretty,” “many children,” “suffering.” Some entries, like “calloused hands” and “like to dance” appeared in both columns.

Having learned through their discussions that gender was a socially constructed power relation between men and women, the participants moved on to consider how it shaped local institutions: the Church, community associations, family agriculture, and rural workers’ unions. It was a perspective I was familiar with from reading Princeton feminist historian Joan Scott’s work. What was not familiar was seeing her post-structuralist theoretical discussion brought to life in this context, so far from the halls of Northern feminist academe.

It was evident that despite the remoteness of the setting and the poverty of the participants, this women’s movement was linked to discourses with roots half a world away. Even in the far reaches of the sertão, the local had no fixed boundaries. At the same time, this was not a case of overbearing global cultural forces penetrating a helpless and backward social sector. In the discussion I observed, participants with their own political histories and context engaged the unfamiliar discourse and made it their own. Given their precarious standing as members of an agricultural peasant class in the late twentieth century, the rural women conceived of “gender” in a particular way. At a time when most feminists in the global North were privileging gender over class, this group was linking the two.2 Women of the sertão used gender to strengthen a class-based movement by rebuilding ties with their male comrades on the basis of equality. They were appropriating a transnational resource and reconstructing it to help them meet their own local political challenges.

THEORIZING TRANSNATIONAL CONNECTIONS

Much of the literature on globalization in the late 1980s and early 1990s conveyed an exhilarating but ultimately hopeless view of it as a set of

inexorable forces beyond the control of ordinary human beings. In this dominant genre, flows of capital and technology swept the globe, incorporating the lucky few, while condemning vast regions and populations to “structural irrelevance.” Extrapolating from their economic analysis, those who wrote from this perspective reached the conclusion that the local had also ceased to matter in a political and cultural sense. As Castells’ “space of flows” came to dominate the “space of places,” meaning evaporated from the local—individual places became increasingly isolated from one another and vulnerable to overwhelming outside forces.4

In this scenario, some, like Bauman, saw geographically mobile elites holding the reins of the global system, while others viewed power as more diffuse. Harvey cited the unfolding dynamic of an accelerating capitalism as the causal force, while Castells located control in “the nonhuman capitalist logic of an electronically operated, random processing of information,” to which even powerful economic interests were subject.5 However they conceived of the locus of global power, theorists in this tradition shared the view that inhabitants of the local were spatially confined, lacking in community, and unable to construct their own meanings or articulate their own alternative visions. What resistance there was, they claimed, took the form of a reactionary fundamentalism based on territorial and primal ascribed identities.6

Feminists and other scholars have since challenged this pessimistic portrayal, arguing that capitalist globalization is not a fait accompli, but rather a discourse—a “rape script” of the inevitable penetration of helpless regions and social sectors, in the words of Gibson-Graham.7 The discourse of global power, they argue, masks a heterogeneous set of processes, ridden with contradictions and vulnerabilities. Though capital seeks to extend its reach and universalize its logic, to do so it must come down to earth, engaging with the particularities of social relations at a local level. While globalizing forces do reshape these relationships, Tsing observes that they too are transformed by the “friction” of the encounter.8 Rather than a deus ex machina, feminist critics argue that globalization is a god with feet of clay.

The perspective of pioneering globalization theorists like Bauman, Castells, and Harvey was profoundly rooted in the particular experience of class and class-based movements. Empirical studies have repeatedly shown the ways in which workers have lost ground in the face of the transnationalization of capital, economic restructuring, and the imposed “flexibility” of labor.9 Though unions have long had international ties, and there have been increasing efforts in recent decades to create cross-border solidarities, these have oft en been nationally circumscribed and undermined by the entanglement of workers’ movements with the state. In the case of class-based movements, gloom may have some purchase in the empirical world.10

The effects of globalization on gender relations, however, are much more ambiguous. The flourishing local space of yesteryear, so fondly remembered by globalization theorists, was too often a suffocating enclosure for women in patriarchal families. Though many have seen their class position deteriorate, global flows have not always had the same negative effect on their experiences of gender.11 Nor does the despairing view reflect the kind of globally connected feminism I found even in a “structurally irrelevant” region like the sertão.12 Rather than turning inward or being confined in the local, women’s movements have developed sophisticated and extensive transnational networks over the last several decades. They represent the other face of globalization—the emancipatory possibilities created by new inter-local connections.13

While the perspective once dominant depicted global flows occurring of their own volition and at their own rhythm, feminist researchers have shown how the purposeful activity of social actors—whether Filipina migrant domestic workers, Barbadian “higglers,” Dominican sex workers, or Mexican immigrants to global cities—underpins the global economy.14 In a similar vein, my study finds social movement actors purposefully constituting transnational political relationships.15 The feminists described in this book appropriate and transform discourses, exchange political currencies of legitimacy and authenticity, and negotiate the requirements of international development funding. In the process, their movements transform meanings and material resources as they facilitate their displacement to new contexts.

The recent literature on transnational social movements takes account of these developments among feminists, as well as among indigenous, environmental, peace, human rights, queer, and global justice movements. By chronicling these proliferating forms of activism, social movement scholars have made an indispensable contribution to understanding the forms of agency that have emerged alongside new kinds of domination.16 They explore the ways social movements have responded to global economic restructuring and to a shifting “transnational opportunity structure” with innovative forms of cross-border collaboration.17 Networks, coalitions, transnational social movement organizations, regional and global gatherings, international advocacy campaigns, and Internet-based activism all push politics beyond the confines of the state and form the basis for new kinds of collective identity. At the same time, these authors make the convincing claim that politics has not entirely lost its grounding in the nation-state. There are continuities between domestic and international activism, and the constraints and possibilities of each shape the other.18

However useful, the literature on transnational social movements has limitations for grasping the cultural dimension of cross-border politics. For the most part, its objects of analysis are particular formalized structures— whether they are organizations, such as People’s Global Action; campaigns, such as the Global Campaign for Women’s Human Rights; events, such as the World Social Forum; or venues, such as the United Nations. From this perspective, movements appear as pre-constituted. The focus is on how already existing entities respond to opportunities and obstacles in a globalizing context, rather than on the processes by which movements come into being and sustain alliances.19 The origins and outcomes of particular strategies adopted by collective actors receive much of the scholarly attention. Culture, from this perspective, is viewed primarily as a resource to be used instrumentally for political ends, rather than as fluid sets of meanings that tacitly shape movement practices and discourses.20 Connections like the invisible discursive trajectories that link feminist scholars in Princeton to rural women in the Northeast Brazilian backlands lie outside the scope of this literature.

Then, too, the organizational bias of the literature often leads to an emphasis on social movement entities and campaigns based in or dominated by the global North. Given the disproportionate share of resources and institutional power in the countries of Europe and North America, it is not surprising that most of the formalized transnational organizations have their roots there. Because of this and also because of the location of many scholars in the global North, these groups draw more analytical scrutiny. But such a focus misses the ways South-North dynamics are experienced by movements in much of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.21

This book takes the perspective of feminist movements in the global South and specifically in Latin America, locating them in a larger web of political and cultural relationships. It explores the multiple forms of collaboration and connection—both inside and outside formal structures— that link them to one another and to movements in the global North. Geographer Doreen Massey’s conception of place provides a useful starting point for theorizing transnational social movements in this broader framework. She views globalization as intensifying links between internally differentiated local sites, rather than as simply the growing power of anonymous “global” forces to penetrate and dominate a defenseless local community. The identity of a particular place—or node—in this web consists of its shifting configuration of links to other near and distant locales. The local “matters,” therefore, not simply as a passive and static counterpoint to the global, but as the primary site where globalization is constituted, as well as where its effects are played out.22

This perspective helps us to rethink social movements, not as bounded entities, but as relational constructs, nodes in a larger web of connections. I argue that, like local places, oppositional social movements, and the organizations that give them concrete expression, come to be through their relationships—with members and allies, as well as with dominant institutions. Their politics—goals, strategies, structures—are defined through their engagement with others; there is no essence that exists outside these connections. Social movements do not have relationships; they are relationships: a set of always shifting interactions with a variety of allies and interlocutors, whether individuals, organizations, discourses, or other social structures.

As this study will show, social movement connections are the source of their greatest power and deepest vulnerabilities. The “goods” that flow through these linkages, and sometimes remake them in unexpected ways, are both material and intangible. Social movement relationships are vectors for discursive travel, as well as the transfer of resources.23 Organizations do not simply absorb all of the discourses that pass their way; they make choices about which new meanings to incorporate and how to reinterpret them. However, their choices are increasingly constrained as the reach of the global market extends into new social spaces.