This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

It's the real stories, not the publicists' confections, that concern Colin Escott. We hear Perry Como's story in his own words: it wasn't all smooth. We learn about the astonishing twists and turns in Roy Orbison's life, and the stories behind the songs we know so well. And we go down with Vernon Oxford, the last great honky tonk singer, who came to Nashville just a little too late. These are stories for anyone who loves what Escott calls "little songs from great sorrows." They will fascinate even the most casual fan of popular music, and they're told here in sympathetic, engaging, and illuminating prose.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Roadkill on the Three-Chord Highway by Colin Escott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Smoother Side of Town

Chapter 1

Roy Orbison

Starlight Lit My Lonesomeness

F. Scott Fitzgerald surely couldn’t have written “There are no second acts in American lives” if he’d witnessed Roy Orbison’s astonishing rebirth. Most rock stars die dreaming of the Big Comeback, but Roy Orbison died in the middle of one.

Through all the upturns and downturns, Orbison seemed to maintain a Zen-like calm. When interviewers spoke to him during the last months of his life, he was polite and deferential, taking his renewed success in stride. Eighteen years earlier, in 1970, when Orbison was a negative equity pop star, Martin Hawkins and I spoke to him backstage at a pitifully small theater in an English coastal town. If he was wondering what ghastly turn of fate had brought him to a half-empty house in a dreary off-season English seaside resort, it didn’t show. He was polite, deferential, and willing to talk for ages to two neophyte journalists with no credentials whatsoever.

Roy Orbison was a true enigma. Born in Texas, he recorded in Nashville and lived most of his life there, yet wasn’t a country artist. Not only was there no “country” in his music, there was almost no “southernness.” His greatest recordings are curiously timeless and placeless. He was the lonely blue boy out on the weekend: got a car—no date. Equally intriguing is the fact that his signature hit “Only the Lonely” wasn’t a progression from earlier singles. It’s almost as if the nine previous records were by another Roy Orbison.

These days, if a record bores or irritates you, it does so for at least four

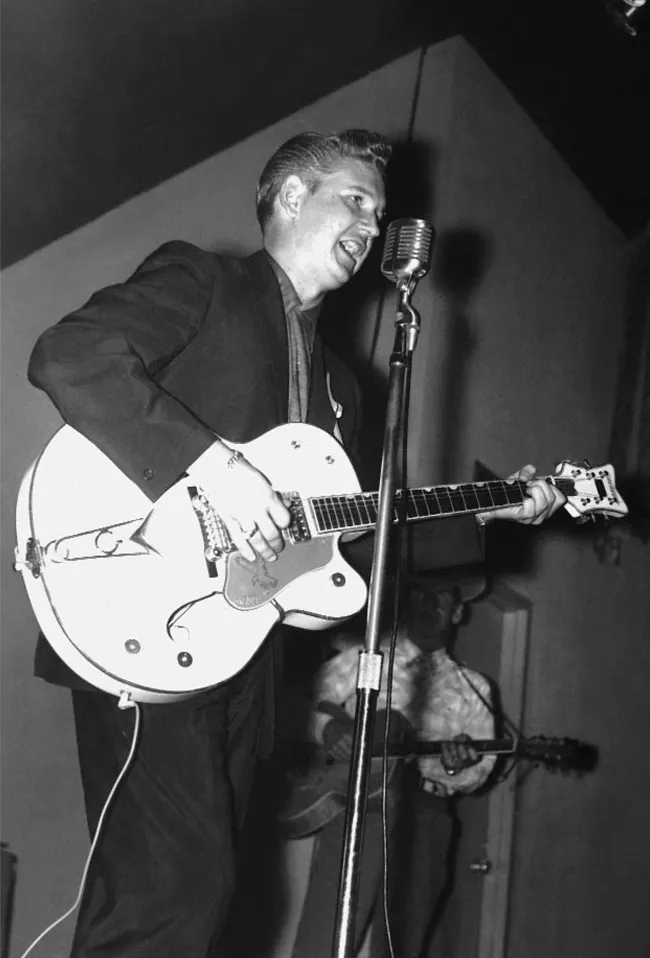

Roy Orbison, c. 1960. Courtesy Bear Family Archive.

or five minutes. Roy Orbison came from a different era. He understood compression. He’d relate a short story or imprint his mood on you in twoand-a-half minutes. The great Roy Orbison records were perfect pop symphonettes. Bruce Springsteen especially admired the little introductions that “synthesized everything down so perfectly.” Two-and-a-half minutes later came the Kleenex Klimax. Not a surplus word or note.

Roy Orbison was a star, yet not. His biggest hits came during the early and mid-1960s pretty-boy era, but there were no stories in 16 magazine. “My dream date with Roy Orbison”?—not likely. “Roy’s Pet Peeves”?— who cared? He was the career outsider. “Only the lonely know the way I feel” after all.

Orbison’s music was very much his own, setting him apart in that era. He wrote most of the songs and effectively coproduced his sessions, which made him a prophet of sorts. Within a few years, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Beach Boys, among many others, would be clamoring for that same level of artistic control. Orbison stretched the boundaries and unsettled the imagination. What or where was a Blue Bayou? Nowhere I’d been. Sometimes, he was almost surreal. “In Dreams” was a deliciously poetic record that seem to drift out of the shadows: “A candy colored clown they call the sandman tiptoes to my room every night. …” Very different; delivered in that voice, very weird. Even the name Roy Orbison had a touch of unreality. Do you know anyone else called “Orbison”?

Two biographers couldn’t quite come to terms with the fact that Roy Orbison’s life was, by rock star standards, untainted by perversion or paranoia. This little piece tries to unravel the music more than the man, although, of course, the two are inextricable. Roy Orbison’s great records were far outnumbered by middling-to-bad records, but for four years he was the most innovative artist in popular music. How did he suddenly elevate himself to greatness in 1960? Why did it all dissolve so fast? Why was he playing a half-empty auditorium in an off-season British coastal resort just five years after topping all the charts in 1965?

Willie Nelson and Texas mythologists would be hard-pressed to find romance in the part of west Texas where Roy Orbison grew up. It’s as desolate as anywhere in the world. There seem to be just two colors: light tan and brown. No one seems to know where the Orbisons came from or how they ended up there. Local history files in North Carolina carry references to Orbisons as far back as the 1750s, but we know little of Roy’s immediate forebears. His father, Orbie Lee, was born in Texas on January 8, 1913, and his mother, Nadine Schultz Orbison, was born on July 25, 1914. Orbie was a rigger, holding down a hard job in a brutally inhospitable climate. Roy was born in Vernon, Texas, on April 23, 1936, but Orbie Lee and Nadine moved to Fort Worth to work in the defense plants shortly after the United States entered the Second World War. It was there that Roy acquired his first guitar. Orbie taught him some chords, and took him to see Ernest Tubb playing on the back of a flatbed truck.

The story of Roy’s earlier years has been pieced together in the biographies, so there’s little need to recap much of it here. Very briefly, he was sent back to Vernon in 1942 because of a polio epidemic in Fort Worth. While there, he made his first radio appearance on KVWC (a delightful acronym for Keep Vernon Women Clean). He performed every Saturday for a while, bicycling down to the station. After the war, the Orbisons moved to the Permian Oil Basin. Roy was an albino with chronically poor eyesight. He wasn’t good-looking; he had no money; and he lived in a town called Wink. “Football, oilfields, oil, grease, and sand,” was how he later characterized that part of west Texas; he rarely if ever went back. Wink tried to claim him as its own, but Orbison was having none of it. He felt an apartness from an early age. “You know,” he said later, “I wrote ‘Only the Lonely’ in west Texas.” The implication was obvious.

Roy began to dye his sandy hair black at an early age, and heard something in his voice that promised deliverance from a bleakly predictable future. As he said later, “I didn’t think it was a good voice, but I thought it was a voice you would remember if you heard it again.” Talking about music with David Booth, he said, “My first music was country. I grew up with country radio in Texas. The first singer I heard on the radio who really slayed me was Lefty Frizzell. He had this technique which involved sliding syllables together that really blew me away.” Roy and Orbie went to see Lefty. They pulled into the parking lot and saw a car sticking out ten feet farther than all other cars. It was Lefty’s Cadillac, and its image seared itself into Roy’s brain. You could drive out of Wink in that Cadillac; drive out and never look back. When Roy signed a buddy’s high school yearbook it was as “Roy ‘Lefty Frizzell’ Orbison,” and when he joined the Traveling Wilburys toward the end of his life it was as Lefty Wilbury. For all that, Lefty Frizzell doesn’t explain Roy Orbison, not in the way that Lefty explains, say, Merle Haggard.

Around 1949, Roy’s buddy, Billy Pat Ellis, borrowed the high school drum kit, and he and Roy put together a band, the Wink Westerners. They appeared on KERB in Kermit, Texas, and the character of their music can be judged by their name and the Roy Rogers bandanas tied jauntily around their necks. “We played whatever was hot,” recalled mandolinist James Morrow. “Lefty Frizzell, Slim Whitman, Webb Pierce … we did a lot of their numbers. We also played a lot of Glenn Miller–styled songs, like ‘Stardust’ and ‘Moonlight Serenade,’ which we adapted for string instruments. I played the electric mandolin and later the saxophone. I fed the mandolin through an Echoplex amp so it sounded like an organ sometimes.” Morrow’s electric mandolin had an eerie sound that complemented Roy’s voice, but there were many bands as good or unusual as the Wink Westerners—and many better.

In his 1954 high school yearbook, Roy spelled out his ambitions: “To lead a western band / Is his after school wish / And of course to marry / A beautiful dish.” And he did, and he did. In the fall of 1954, he went to North Texas State College in Denton, and subsequently transferred to Odessa Junior College for his second year. He studied geology in Denton, preparing to follow his father into the oilfields if all else failed, but, after flunking his first year exams, he switched to English and history.

The Wink Westerners became the Teen Kings, and the explanation for the name change is simple: Elvis. Those yellow Sun records from Memphis turned Roy Orbison’s head around. It’s hard to date the epiphany because Elvis all but lived in mid- and west Texas in 1955, and he was on the Louisiana Hayride, which blanketed Texas, every week. “I was at the University of North Texas,” Roy recalled, “and my father wrote me a letter. He said he had seen a concert with Elvis Presley and it was terrible. He said this greasy-haired kid came out and stole the show. Anyway, Elvis came to town and about four hundred of us showed up. It had to be late summer because everyone had gotten on trains and gone to Abilene to see a football game. Elvis came out and I thought I saw him spit onto the stage. As he walked out, he just went Puhhh. It was him, Scotty Moore, Bill Black, Floyd Cramer, and my old drummer. The show was pretty good. He sang a lot of other people’s songs.” Elvis was in Odessa in February 1955, but Roy would have been in Denton at the time, so perhaps this was the show that Orbie saw. Then Elvis was at the Big “D” Jamboree (within driving distance of Denton) in April 1955 and back in west Texas in June, August, September, and October 1955. Roy could have been at any or all of those dates.

Frat party days. Left to right: Jack Kennelly, Johnny Wilson, Roy, Billy Pat Ellis, James Morrow. Courtesy Bear Family Archive.

The Teen Kings won a talent contest sponsored by the Pioneer Furniture company in Midland, and the prize was a television appearance. Roy persuaded Pioneer to sponsor a Friday night show on KMID-TV and a Saturday afternoon show on KOSA-TV Odessa. Television was a novelty in west Texas, but Roy was amazed how many more people turned up at their gigs once they started announcing them on television: another epiphany.

Roy returned from Denton with an original song, “Ooby Dooby.” He’d learned it from two fellow students, Wade Moore and Dick Penner, who had written it in fifteen minutes on the flat roof of the frat house at North Texas State. Roy had seen them perform it onstage at a free concert. “They sang this song and the people went crazy,” he remembered. So he sang it too. It appears as though Roy first recorded it at some point in late 1955 or early 1956 during a demo session, possibly at Jim Beck’s studio in Dallas. Beck scouted acts for Columbia Records’ head of country A&R, Don Law, although Roy remembered that the audition was held by someone called “Green.” It’s possible that he was thinking of RCA’s roving A&R man, Charlie Grean. Roy was friends with Charline Arthur, a female rockabilly singer of uncertain sexual orientation, who recorded in Dallas for RCA, so it’s possible that she arranged an audition with Grean.

Columbia’s Don Law had signed Lefty Frizzell, but saw no merit in Roy “Lefty Frizzell” Orbison. He gave the acetate to one of his contracted artists, though, and the otherwise forgotten Sid King recorded “Ooby Dooby” on March 5, 1956. One day earlier, Roy Orbison cut the song at Norman Petty’s studio in Clovis, New Mexico, together with “Trying to Get to You.” It became the first release on Je-Wel Records. (Je-Wel was a rough acronym for JEan Oliver and WELdon Rogers.) The Je-Wel story isn’t really relevant to our story, and doesn’t explain where “Only the Lonely” came from, but it’s a fascinating little sidebar that says something about the usually well-disguised Orbison ambition.

Je-Wel was underwritten by Jean Oliver’s oil executive father, Chester. “We had this TV show on Channel 2 in Midland,” Weldon Rogers told Kevin Coffey.

Just before we came on for thirty minutes there was a young band on for thirty minutes. It was Roy Orbison and the Teen Kings. So, anyway, we had a session set—we were going to do a session at Norman Petty’s—and the gentleman that went in with me on this deal, Chester Oliver, said, “Did you listen to them boys in there?” I said, “Yeah, I listened to them.” He said, “What do you think?” I said, “Well, they don’t play my kind of music, but I tell you what, they are very, very good for the type of music they do. They’re tops.” He said, “Well, I was thinking we ought to go talk to this young man that’s the head of the group—what’s his name?” I said, “Orbison? Roy Orbison? He goes to college out at Odessa.” He said, “Let’s go talk to him to see if they’d be interested in recording. Do you think it’d sell?” I said, “Yep. It sure would.” So we talked to him a night or so later, went over to his apartment in Odessa. … He said, “Well, I’ve been turned down by every record label there is … we’ve tried’em all.” I said, “Well, we’ll put you on a label and if it does what I think it will, you’ll get a label deal—I plan on getting you a good deal on a label.”

The Olivers lived in Seminole, Texas, sixty miles north of Odessa and 150 miles from Clovis. Roy’s mandolin player, James Morrow, claimed at one point that he dated Jean Oliver and paid for the Clovis session. Roy once insisted that he paid for it, but in an interview with Glenn A. Baker he confirmed Rogers’s account: “There were some people in Seminole, Texas who wanted me to make a record for them, so they paid for the time. It was the first custom session Norman Petty ever did.” Within a year, Petty would be working with Buddy Holly and forging a little musical frontier in Clovis. In retrospect, Roy might have been well-advised to hang around.

“I was selling those records just as fast as I could peddle’em,” said Rogers.

They were selling faster than I could get’em pressed. Sid Wakefield out in Phoenix, Arizona pressed the record for me and did a good job. We were selling records galore. Cecil Holifield had a record shop in Odessa and a record shop in Midland. He was selling a lot of those records. I went back about a third time to take him a hundred. There was a music store in Lubbock that bought’em 250 at a time—and a week later they called, “Hey, I’m out! I need some more.” It was doing that well. Well, Cecil Holifield, it stirred him up. [He] picked up the phone down there and called Sam Phillips at Sun Records in Memphis. When I signed a contract with Roy Orbison, age did not enter my mind or Mr. Oliver’s mind. We just took for granted that he was of age. Well, he wasn’t. He was only nineteen. We didn’t ask him. He didn’t tell us. He signed the contract—but you know about how much that was worth. And that’s what Cecil Holifield called Sam Phillips and told him: “I got some boys out that’s got a record that’s just selling like hotcakes and this old boy that signed him to a contract don’t know that he’s just nineteen. If you’ll get them down there and record them, you can make a mint with this old boy.” So Sam Phillips got in touch with Roy, said, “You boys come on down. Bring your father to sign the contract with you.” In the meantime, they filed an injunction against me and Mr. Oliver in the district court in Odessa, an injunction to stop me from selling his records.

Roy more or less bears out Rogers’s account. The Je-Wel record had probably been on the market no more than a few days or weeks when Sam Phillips approached Roy. “I took this recording from Clovis to Cecil Holifield,” Roy told Baker. “He played it on the phone for Sam Phillips. Called Sam on the spur of the moment right there. Sam said, ‘Can’t hear anything. You’ll have to send it to me.’ He sent it and Sam called Mr. Holifield and Mr. Holifield called us and said, ‘Can you be in Memphis in three days?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, we will.’ I was under contract but I had the opportunity to be on Sun Records, so I asked my dad about it. ‘What am I gonna do here?’” It was probably Phillips’s idea, not Orbie Lee’s, to ask if Roy had been twenty-one when he signed the contract, and it was almost certainly Phillips’s idea to slap a cease-and-desist on Rogers and Oliver. A district judge ruled against Je-Wel, and then, according to Rogers, “The judge ordered me to give Roy all of the records that I had on hand … about fifty is all I had with me. So I gave’em to him. Later on, I went back to Norman Petty’s and I told Norman what happened. It made Norman [mad]—it hacked him off pretty good. He said, ‘What exactly did that judge tell you?’ I said, ‘He told me that I had to turn over all the records that are on hand to Roy Orbison.’ ‘Did he tell you, “Do not press any more?”’ I said, ‘No, Norman, he didn’t tell me that. There wasn’t anything said about that.’ ‘You need quite a few of’em, don’t you?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He reached over and got the phone, said, ‘This call’s on me.’ He called Sid Wakefield in Phoenix and said, ‘Press this Je-Wel 101—press five thousand up and send’em to me just as soon as you can get’em here.’ So, anyway, we sold another five thousand records of that—except for about a dozen that I kept.” This would certainly account for the fact that, although rare, Je-Wel 101 is available with several different label backgrounds and is nowhere near as hard to find as it would be if it had been on the market just a few weeks.

Roy Orbison on Sun Records is one of the great comic horror stories of the record business. Rarely was an artist so misunderstood, especially by someone who had such a sparkling track record, as did Sam Phillips. It seems as though Phillips’s golden ear told him that he was onto something, but didn’t tell him what it was. For Roy Orbison, Sun Records was the celestial city. He was standing where Elvis had stood. The idea of saying no to “Mr. Phillips” was unthinkable. Roy knew how many kids simply wanted the opportunity because he saw them lined up outside the studio, and saw the tapes arrive in the morning mail.

“My first reaction,” Phillips recalled many years later, “was that ‘Ooby Dooby’ was a novelty type thing that resembled some of the novelty hits from the thirties and forties. I thought if we got a good cut on it, we could get some attention. Even more I was impressed with the inflection Roy brought to it. In fact, I think I was more impressed than Roy.” This was an astute observation. Some say that rock ‘n’ roll was R&B under another name, yet songs like “Ooby Dooby” and “Be Bop-a-Lula” were closer in many ways to dumb old pop novelty songs like “Hoop-Dee-Doo” than to R&B or blues. R&B was adult music; rock ‘n’ roll was not. “Ooby Dooby” certainly wasn’t.

Sensing that “Ooby Dooby” might break like “Blue Suede Shoes,” Phillips moved fast, bringing the Teen Kings to Sun in late March or early April 1956 to rerecord the song. According to Weldon Rogers, Phillips called him during the session:

After all of this, Sam Phillips had the nerve to call me one night at home when they were doing the session down there. [He] couldn’t get the sound in his studio that Norman Petty had gotten. H...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART I The Smoother Side of Town

- PART II Fabor

- PART III Town Hall Party

- PART IV Memphis Sun Records, June 1957

- PART V Postscript

- Index