Chapter 1

What are we really doing to patients?

We have all, from time to time, experienced debilitating illness. Many of us have faced serious illness or its possibility, or faced the uncertainties and dangers of pregnancy, or of trauma and so on. Almost without exception on these occasions we have consulted our doctor wanting to know what is wrong with us, or what is the solution to our problem to ensure continued health. We have depended on the doctor’s diagnostic and therapeutic skills and been assured by authoritative answers to our questions. It is not difficult therefore to succumb to the temptation to perceive the doctor as the custodian of a treasury of secure and objective knowledge about us in these extremely important areas of our life. It is also understandable that doctors too will be tempted to think that they can, with some authority, determine what we really need, and be confident of what they are really doing to us in the clinic. But are things as straightforward as this?

The search for precision in our description of the world and the related quest to secure our knowledge of the world about us started long before the beginnings of modern medicine. It characterised the history of Philosophy from its beginnings. These two enterprises are often referred to in terms of the relation between language and reality. The first concerns the question of what it is that distinguishes a meaningless jumble of marks or sounds from a written or spoken sentence. How precisely does language latch on to reality, to the world which we inhabit? The second concerns the question of whether we can be certain that our view of the world about us is authoritative. Each of these questions applies to the world of medicine in which we are specifically concerned to describe the human condition as carefully as possible and extend our knowledge of the same so as to identify its ills and develop means to provide help to those in need.

There are two reasons for approaching this quest in medicine and health care by the circuitous route of reviewing the manner in which philosophers have dealt with the general issues. The first is to avoid the impression that the philosopher is somehow prejudiced against medicine and those who profess it when he or she engages in critical reflection upon its subject matter. The philosophical worries that concern us in this chapter apply equally in all realms of human activity from shoe repairing or cobbling to administering health care. Socrates was condemned as a meddler in the business of others for asking questions about the nature of their activities. Indeed even cobblers were not beyond the range of his interests. Philosophers have, more recently, been similarly condemned by doctors for reflecting upon their practice.1

The second reason is to enable us to ask the correct questions about what we are doing when we describe health and illness states and prescribe interventions to deal with those states. In short it is to help us determine how much sense there is in the question which forms the title of this chapter and to explore the consequences of the temptation to think that we can or ought to endeavour to give a definitive answer to it as it stands. In particular the object will be both to illustrate how values enter inevitably into the picture and to point out the crucial importance of this dimension of the language of health care.

The innocence of language

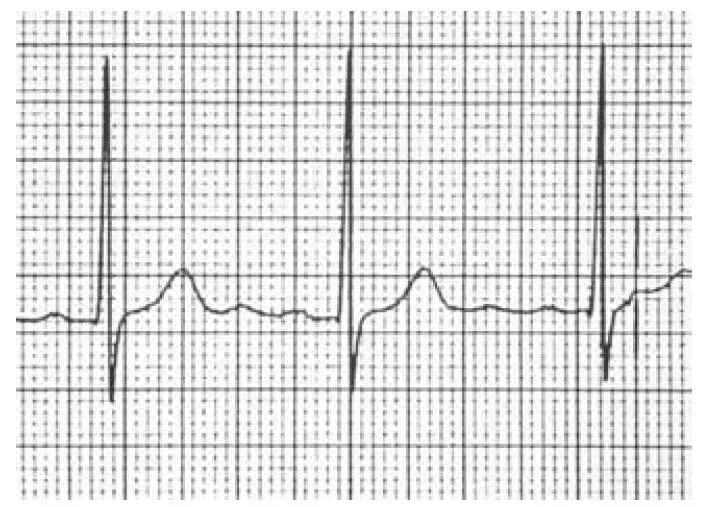

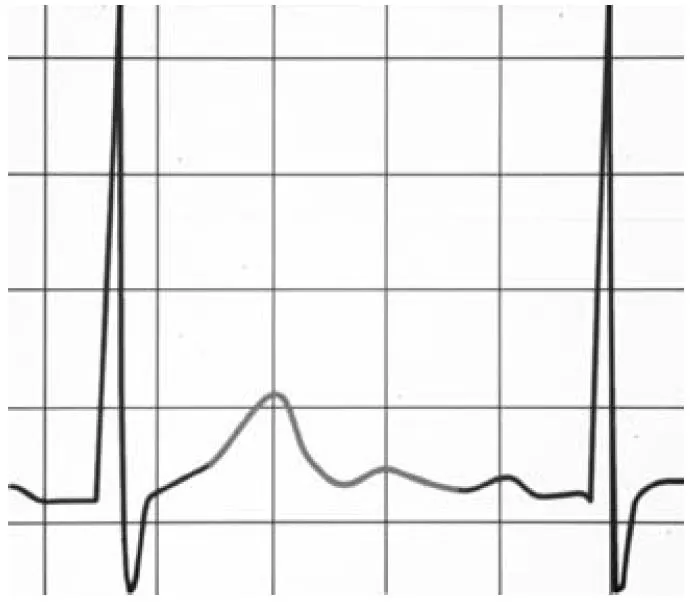

How would we respond if asked to describe the real significance of the following images? (See Figs 1.1 and 1.2 below.)

We might imagine that it is more challenging to formulate a response to the first than to the second image. Yet, as we shall see a little later, each response runs into the same logical problems.

Philosophers are often thought to be preoccupied with language. There is a good reason for this interest for the central question of Philosophy from its beginnings has centred around how it is that sounds we utter and signs we make and write can be significant. For example, what is it that gives the two images meaning? Or more generally, when we make claims about the world around us how is it that the noises we utter or the marks we make relate to the real world? What is it which makes it possible to refer to things in the world and to make utterances which can be true or false as opposed to meaningless?

The language of facts

The most influential and enduring answer to this question goes back to Plato and has survived through Augustine to this century when many believed it found its apotheosis in the early work of Ludwig Wittgenstein.2 He was to go on to make fundamental criticisms of the account3 which we shall note.4 Despite these criticisms and as testimony to the power of the temptation to seek answers to the question: ‘What are we really doing when we say something?’, newer versions of the account have been espoused by contemporary philosophers.5

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

The account has an immediate appeal to common sense in that it appears to reflect the way in which we teach children to read and associate signs with things in the world about them, that is by pointing. The claim is that the fundamental activity involved in language is that of naming. A simple word or sign has an immediate relationship with what it signifies, viz. its meaning is the object it names. Of course there can be more complex signs which get their meaning from a combination of the simple signs which make them up. Hieroglyphics present us with a perspicuous model of this account where relatively simple pictures denote individual objects and they can play a part in a more complex picture enabling us to say things about the relationship between the objects referred to in the world – that is to make an assertion. However, from Plato onwards philosophers quested for even more simple signs than these primitive pictures. They wanted signs which would rule out ambiguity and somehow link with reality in an unmediated way – that is in a way which did not depend on human agency at all. This would guarantee an authentic relation with reality eliminating arbitrariness.

Perhaps one of the best approximations to this primitive relationship is found in colour words. If we wish to teach a child the meaning of a colour word then we use the word in relation to objects we point out bearing the colour – the yellow teddy bear on the page of the book, the banana on the table, the custard in the dish, and so on. We then hope that the child will catch on to the sequence and be able to go on to identify other objects which are similar in this specific regard. When it is able so to do we believe that we have established the immediate relation between the word and the colour for the child – that it has learned the meaning of the word by recognising its bearer other than by understanding a definition, as no definition (which would be something akin to a description of yellow in more basic terms) is possible. But we cannot achieve this with a blind child precisely because we cannot confront her with the object which is the bearer of the name ‘yellow’ and therefore we cannot establish the immediate relationship. That child is forever cut off from understanding the word. On this account, according to Plato ‘the essence of speech is the composition of names’.6

But in order to say something it is necessary to do more than simply identify things; one has to assert something about the relation between those things. For example, to point at a cat and utter ‘cat’, or to a mat and utter ‘mat’ is not to say anything. But to link them as in ‘the cat is on the mat’ is to make a claim which could be true or false depending on the circumstances which prevail in the world. For this reason it is the composition of names which Plato thought was ultimately important for meaning. Here too there has been a quest for such combinations – propositions – which are absolutely unambiguous, such as Wittgenstein’s elementary propositions, which were supposed to be primitive pictures of reality. But the big question philosophers had to answer was whether such activities as naming and picturing could be primitive in order to secure a link between language and the world.

There are many difficulties attaching to each of these phases of an account of meaning but before visiting them briefly let us ask what could be the relevance of such interests to the world of medicine and health care. Here too, of course, we are committed to trying to understand the world with which we are presented, identifying particular features of that world – such as biological phenomena – and making sense of them, that is seeing their significance in relation to other features of the world such as their role in determining the health state of a person presenting with the feature in question. The vastly increased influence of science in the practice of medicine over the past three centuries has led us to believe that we have made great progress in furthering our understanding of the human condition. The authority of scientific descriptions and explanations of bodily states has replaced what are now seen as rather speculative and fanciful descriptions and explanations, bringing us closer up against the realities of health and disease. Consider, as a simple example, Harvey’s discovery of the function of the heart as a pump circulating the blood and thereby oxygenating the tissues of the body. It is hard for us to imagine the kind of sense made of so many physiological conditions prior to this advance in understanding or, indeed, what more accurate account of the matter could ever be given beyond more detailed information as to how such a function is facilitated in terms of electrical discharges, and so on. It is here that we have to avoid the temptation alluded to in the case of the philosopher who was concerned with the more general problems of meaning for fear of attributing more authority to our descriptions and understanding than we are entitled, as we shall later see in a number of contexts of health care provision.

What then are the problems attaching to the notion of the innocence of the language of facts which is bound up with the alleged fundamental activities of naming and picturing? Consider the first phase of naming particulars. Is the activity of pointing really an unambiguous activity and could it be the fundamental activity in language use? Wittgenstein came to see that his claim that ‘a name cannot be dissected any further by means of a definition: it is a primitive sign’7 could not stand as an account of the beginnings of language for one already has to be a master of language, in a sense, before naming is possible at all. Pointing, the activity involved in ostensive definition, is not unambiguous and the person being instructed might well misunderstand what is meant by the teacher. To take the most plausible example discussed earlier, viz. the colour yellow, we must note that pointing to a banana and saying ‘yellow’ does not inevitably make the link between the sign and the colour. The learner might think that we refer to the shape of the object, or to the number of objects, or to its situation of being at rest or a multitude of other things. Unless he is aware that we are referring to the colour of the object then there is no guarantee that he will take our pointing as we intend him to. But the presence of this ‘colour space’ at which to station the word ‘yellow’ assumes a whole social practice of making colour distinctions which has to be absorbed to a degree by the child before the specific naming of colours to a child will be possible. Up to a point then, what one really sees is determined by a whole series of expectations and shaped by familiar practices and contexts.

Let us return to our first image for a moment to illustrate the point. To ask what is it that we really see when confronted by the squiggle in isolation is puzzling. It might be something significant or not – no more than a squiggle. But now view the same squiggle in context and it takes on an unmistakable significance for the viewer who has mastered certain skills. Some of those skills are commonplace, such as our reading of two-dimensional drawings, a skill we master very early in life.

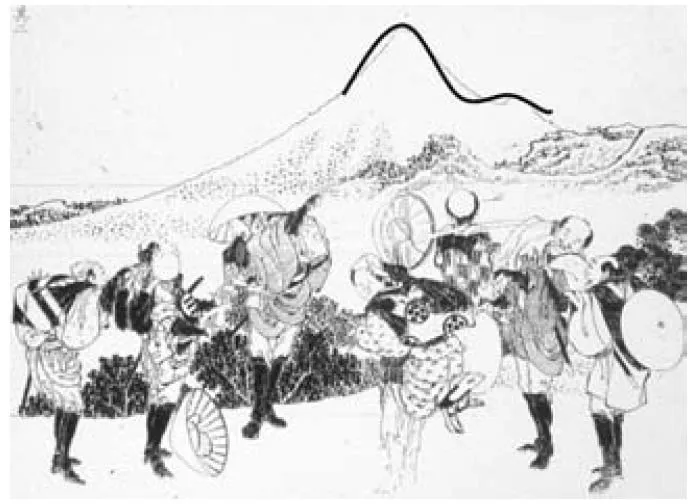

This woodcut (see p. 6), is number eight of the One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai.8 It is his only drawing showing the blemish on the perfect form of the mountain – the projection on the right-hand side. This was a representation of the crater formation left by the great eruption of 1707 which formed Mount Hoei. Though one might not be able to identify the background shape as Mount Fuji, nevertheless one recognises it as a mountain or a large hill pretty easily. One might be surprised to discover that our squiggle is part of the mountain profile.

Figure 1.3 Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), woodcut, number 8 from One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji.

Have we now discovered its significance? Can we say what we really saw earlier in the paper? The answer is no for if we place it in another context we shall see something quite different.

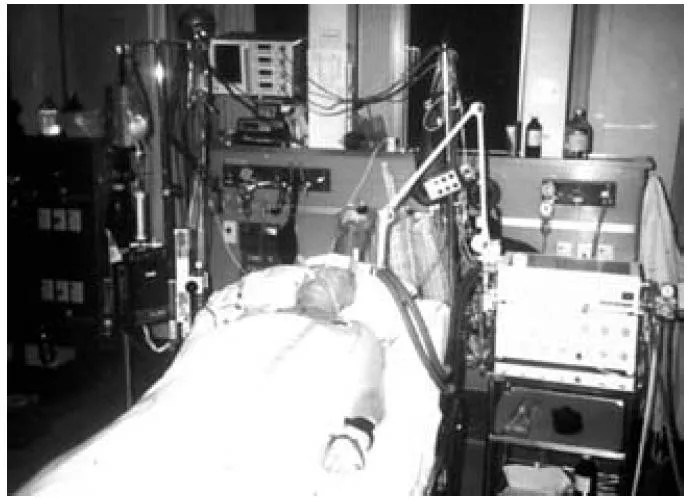

This electrocardiogram is one taken to trace the heartbeat of the author prior to the implementation of anaesthetic procedures for surgery (see Figs. 1.4 and 1.5 opposite). The skills which have to be mastered to invest this kind of significance in the squiggle are rarer, of course, but no less social or public in character. But we might, in a moment of revelry, note an interesting feature of the image (see Fig. 1.6).

Imagine the patient’s concern if the attending clinician employing this trace at the bedside had remarked on the elegance of Mount Fuji in the patient’s records. This would not merely have been highly unlikely, it would also have been a total distraction. The trace was not such a representation; rather it was made up of the T wave and the U wave in the cycle of his heartbeat – the former representing the ventricular muscle repolarisation of the heartbeat and the U wave being of, as yet, uncertain significance. What it was, however, could not have been recognised in the absence of other reading skills facilitating the identification of the squiggle as a phase in the heartbeat, skills attaching to the theory of muscle activity and electrical discharge as summed up in Fig. 1.7 opposite.9

Figure 1.4

Figure 1.5

Figure 1.6

Thus the relation between the sign and the signified is not an innocent one, is not sacrosanct and immediate, but is one which is mediated by some kind of social convention.10

No more could the relation of picturing be prim...