This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Captive Images examines the law's treatment of photographic evidence and uses it to investigate the relationship between law, image and fantasy. Based around the scholarly examination of a bank robbery, in which a surveillance camera captures the robbery in progress, Katherine Biber draws upon critical writing from psychoanalysis, postcolonialism, art, law, literature and feminism to 'read' this crime, its texts and its images.

The result is an interdisciplinary study of crime that unfolds a compelling narrative about race relations, national identity and fear.

This book is an essential read for all levels of law students studying, or interested in, law, criminology and cultural studies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Captive Images by Katherine Biber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The hooded bandit

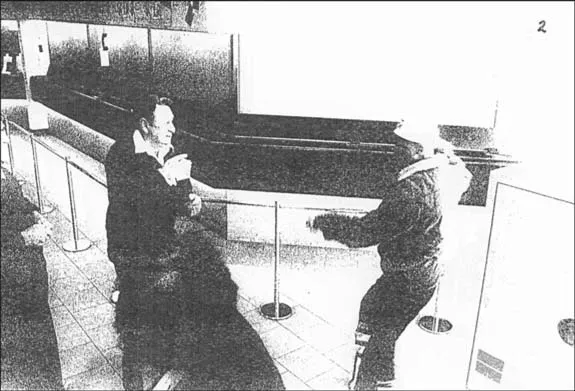

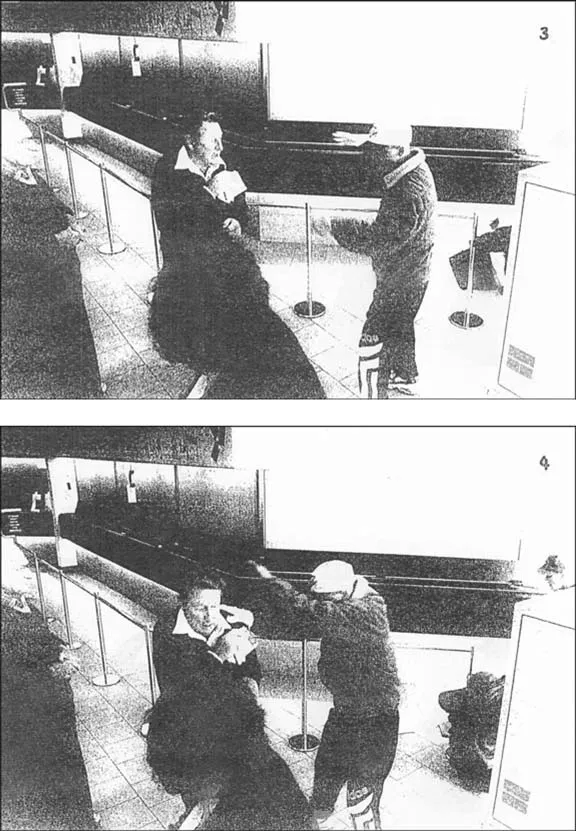

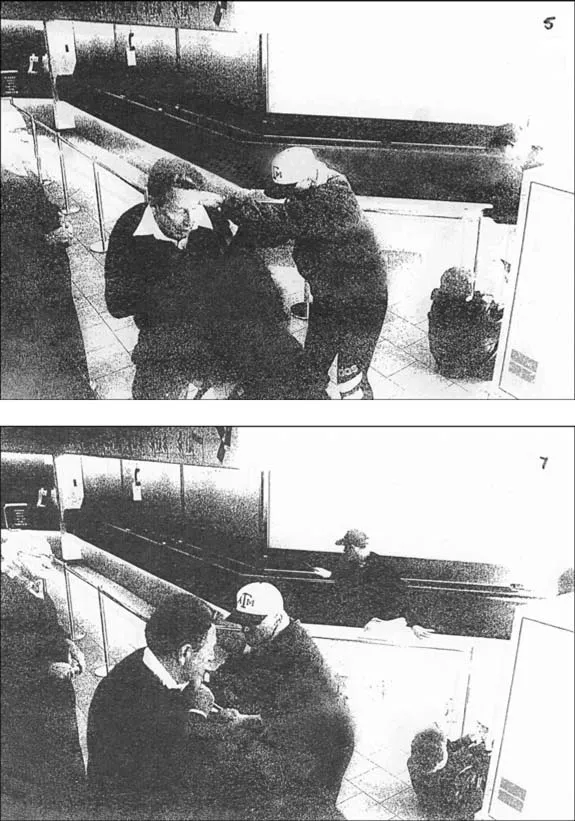

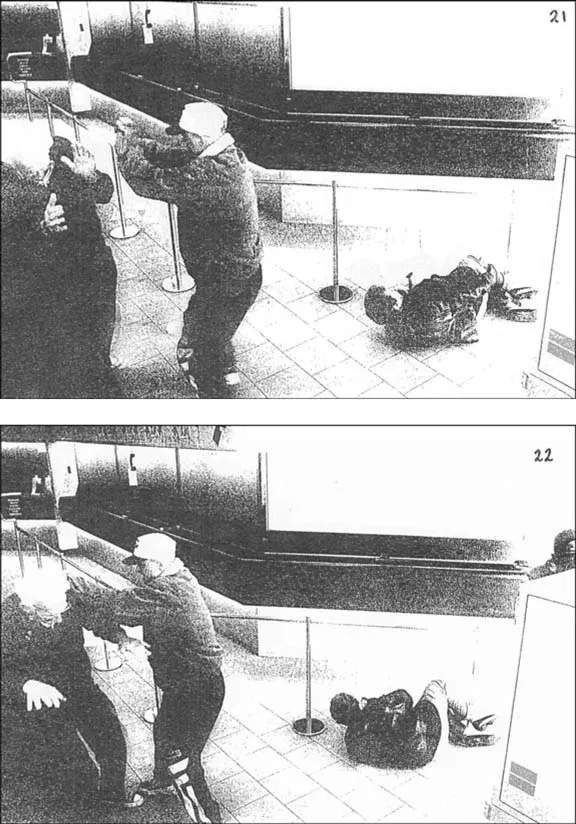

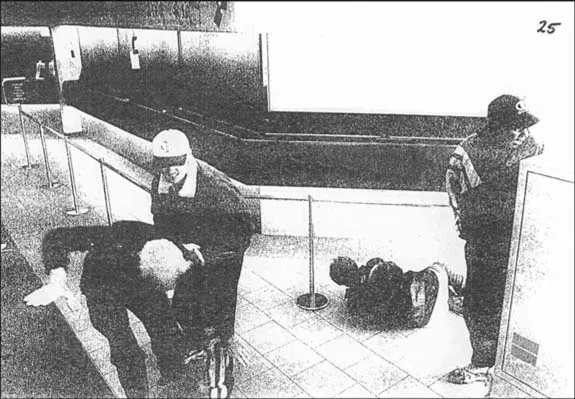

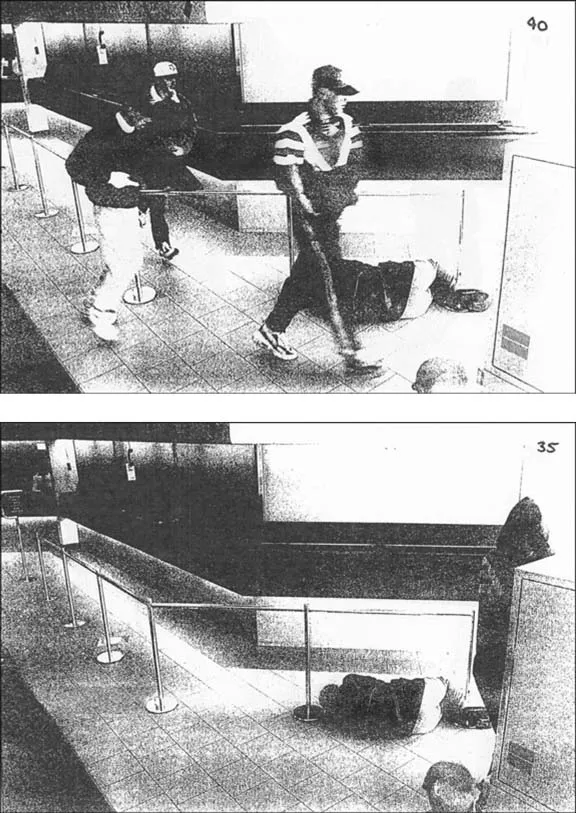

One Thursday at lunchtime, in a quiet Sydney suburb, the local branch of the National Australia Bank was robbed. Four male youths launched themselves into the bank wearing baseball caps, tracksuits and white gloves. One jumped over the counter and wrestled with a bank teller before the security screens were activated. Someone thought they saw a screwdriver being used to open drawers containing money. There was shouting and swearing and a woman lay on the floor, curled in a foetal position, ardently not looking at what was happening around her. The surveillance camera was triggered, capturing one photograph illustrating each second of the robbery. In the photographs, which are black and white and mostly grainy, we can see, frame by frame, one elderly man being pushed to the ground by a young bandit as another elderly man watches. This second man – each frame represents his hands moving incrementally, first to protect his head, then to break his fall – is pushed to the ground as his spectacles fall from his face.

A total of $16,610 is stolen, the final frames show three bandits walking out of the bank in what appears to be a casual stroll, possibly holding the money. The fourth bandit, his face almost entirely concealed by the hooded jacket he wears, stands beside the doorway to the street. He is the look-out. On the wall in front of him is a surveillance camera. The hooded bandit looks directly into it. This man was alleged to be Mundarra Smith, a 19-year-old Aboriginal man, whom two police officers later testified that they recognised in the photographs. On the basis of this testimony, Smith was sentenced to a minimum term of three years and ten months, of which he had served three years and six months before his appeals reached Australia’s highest court, the High Court, which quashed his conviction and ordered a re-trial. His second trial resulted in his acquittal.

Captive Images examines what happens when law tries to prove things from photographs. This book disentangles the unsteady embrace between race and crime, blackness and deviance, and the role of photographs in holding them together. For law, photographs purport to tell the truth; photographs are evidence. The criminal courts pore over photographs, hoping to crack open the secret hidden within the image. Ignoring over one century of scholarship on photography, never attempting to formulate a jurisprudence of the visual, the law looks at photographs as if there were nothing impeding its capacity to see. Captive Images is about a series of photographs which, for three and a half years, alleged that a young black man had robbed a bank, before determining, upon balance, that he had not. This book is about the fantasy that permits law to imagine that decades of criminological, historical and cultural inquiries into race and representation, dispossession and deviance had not intercepted its capacity for vision. Looking at a photograph is not the same as reading a chart, nor like listening to an eyewitness, nor entering a crime scene and dusting and scraping it for clues. The assumption that a photograph is analogous with ‘truth’ has never adequately been addressed by law.

Photographs occupy multiple genres: they remind us of happy moments with our family, nostalgic reflections, memories of places we have been, disastrous images of places we never want to go, people we hope never to meet, our obsessions, our dark desires and our fears. The evidentiary capacity of the photograph needs to grapple with each of these genres, asking what is in these images, and also asking where these images belong. What is a photograph? What is in a photograph? What is the role of these photographs in the lives of these young offenders? Are these proof of their criminality? Snapshots from their youth? Do these form part of an historical record of black men’s conduct and misconduct? Can we compile an album to leaf through later, recalling a time when we surrendered unflinchingly to the fantasy that we could really know the world from these pictures?

In cases where a photograph is clear, its evidentiary capacity seems assumed. At Mundarra Smith’s trial and appeals, where the photographs were unclear, instead of scrutinising the place of photographs in the evidentiary canon, the courts devoted all their attention to determining who is permitted to look at and speak about an unclear photographic image. The doctrinal question that concerns the law is: Can two police officers who know Smith from the streets of a tough inner-city suburb give evidence that they recognised him in the surveillance images? This book deals with this question, which the High Court answered ‘No’, but it also asks other questions: What does it mean to accuse an Aboriginal man of crimes against property in the context of indigenous claims against a nation built upon stolen land? What does it mean when the eyewitnesses to the crime each described the perpetrator as having a different skin colour? Why was the defendant’s mother called as a witness and not shown the photographs? Is it dangerous for the jury to learn that the defendant is known to the police who patrol one of the most notorious areas in the nation? How provocative was it for the High Court to describe the hooded bandit as the spectre from Hamlet? And what can it mean when Mundarra Smith looks at the image of the hooded bandit and says, ‘Doesn’t look like me.’

To look into the photographs in order to find Mundarra Smith is also to look into a space that contains racial difference, criminal conduct, banking, policing and surveillance. These photographs offer a kind of visual confirmation of a psycho-social assumption that conflates blackness with deviance. These images illustrate the evacuation from the inner cities and the ex-urban fringes of social services, networks of family support, educational infrastructure, all replaced by an increasingly threadbare welfare safety net and an increasingly fortified matrix of institutions dedicated to the supervision, surveillance and interception of proscribed misconduct. These photographs are evidence of adolescent misadventure, of misguided masculinity, disrespect for the elderly, for authority, for work, for other people’s possessions. They are images of boredom, poverty, and a craving for adrenaline. These may be Beatrix Campbell’s ‘marauding men’, boys from impoverished housing estates managed – without support and with little effect – by their mothers (Campbell, 1993: 93). And, of course, by the police. These photographs purport to show us what our world looks like. They become a window into ‘drug-related crime’, into ‘bank robberies’, into ‘black crime rates’. Law proceeds as though it does not, or need not, see any of these visual effects. Law imagines that it can quarantine the photograph from all of these social images, asking a single question: Who is this? By privileging law’s question, law provides the definitive caption for the photograph: This is what you see.

Captive Images sees something else in these photographs. This crime signifies something fundamental about race relations, about national identity and colonialism. This book tests whether it is possible to read crime, its images and its texts, as scenes in the management of national space. In White Nation (1998) the anthropologist Ghassan Hage wrote that the nation is a fantasy space, and nationalism is the fantasy of being in charge of it. A compendium of micro-fantasies constitutes the nation. In this fantasy nation, each of us occupies shifting positions. We imagine ourselves as included or excluded, belonging or not belonging, tolerant or tolerated. But the position we occupy is contingent upon our role in everyone else’s fantasy. Each of us may seek to include ourselves within a particular milieu, one that is defined through the exclusion of others. But another’s fantasy may depend upon our own exclusion. This enables us to occupy a particular position and its opposite without impossibility. We contain within ourselves the capacity to fulfil our own fantasy, but we also possess all that our adversary requires to achieve their counter-fantasy. They want to take it from us, claim it, and exclude us. In the endless confrontation of competing fantasies, the fantasy nation is always elsewhere. It is the nation we once were, and lost. It is the nation we could become, if only we remove the obstacle.

This book is about the hooded bandit in the photograph. He is the obstacle to the fantasy nation where money is safe in the bank, where the young show respect for the elderly, where rampaging black men are kept behind bars. To achieve this fantasy, we enact laws, we convene courts, we empower police, we make demands upon parents and – increasingly – we install cameras. The role of the surveillance camera in the fantasy is to be everywhere, to see everything, to remember, to reinforce, to fill the blank space. And to show us what the obstacle looks like. One aim of this book is to interrogate the use of photographic technologies in the policing of minority individuals and communities.

Anecdotal evidence from the Sydney Regional Aboriginal Corporation Legal Service (ALS), which represented Mundarra Smith, suggested that – at the time of these events – at least 20 per cent of Aboriginal defendants – adults and juveniles – were prosecuted for offences arising out of photographic or CCTV surveillance evidence. Now, as entire town centres, transport interchanges and public amenities are brought within the fold of surveillance, those figures would be much higher. In the decade leading up to Mundarra Smith’s successful appeal to the High Court, prosecutions for bank robberies were conducted very simply. The photographs were developed and passed around at police stations in specified areas. Police officers would claim to recognise the perpetrators, who were arrested and brought to trial. The jury was shown the photographs, and heard testimony from the police about their recognition of the defendant from these photographs. The jury would then determine whether, beyond any reasonable doubt, and having looked at the defendant sitting in the dock, they agreed with the police recognition evidence. This method of prosecution had high conviction rates. Eliminating most of the traditional methods of crime investigation and eyewitness examination, the police played the leading role in identifying and intercepting the hooded bandits, the obstacles to achieving the fantasy nation.

This is how Mundarra Smith’s first trial proceeded in the District Court of New South Wales,1 a joint trial with a co-defendant, Jason Nicholas, who was also convicted. The photographs were tendered and police officers were called to testify. The police were from the Redfern patrol, 20 train stations north of the crime scene in Caringbah. Caringbah, in the Sutherland Shire, is notorious for its mono-ethnic whiteness; the Shire’s major beach, Cronulla, was the scene of what the media and politicians called ‘race riots’ in December 2005. Redfern, on the other hand, is famous as the home of urban Aboriginal poverty, high crime rates, and an ever-present needle-exchange van. Two police officers testified that they recognised Smith from the Redfern area, and a third testified that he recognised Nicholas. Both Smith and Nicholas exercised their right to silence. In separate proceedings, Richard Murchie pleaded guilty to the bank robbery, admitting that he was the bandit who jumped over the counter. The fourth prosecution was of a juvenile in the Children’s Court, whose proceedings and findings are closed to the public.

After an unsuccessful appeal to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal,2 Smith’s appeal to the High Court was upheld,3 as were two related appeals brought by the ALS on behalf of Jason Morris and Lee West, who had been convicted of different bank robberies using the same prosecutorial technique.4 The majority of the High Court held that the police recognition evidence was irrelevant and, as irrelevant evidence is prima facie inadmissible, Smith was to be re-tried without the police evidence. His first conviction was quashed and the re-trial held in 2002.

At Smith’s second trial, the jury was simply shown the photographs and asked to compare them with Smith, who sat silently in the dock. They were given additional instructions about the dangers associated with identifications made of Aboriginal people by non-Aboriginal people; an instruction derived from American jurisprudence, where ‘cross-racial identifications’ are in issue, and which are discussed later. The second jury was told of a socio-cultural tendency amongst non-Aborigines to ‘recognise’ features that they associated with Aboriginality, rather than the features of the individual in question. They were told that it was not enough simply to see – in the dock and in the photographs – an Aboriginal man. They needed to be certain beyond a reasonable doubt that both men were Mundarra Smith. They were not certain, and acquitted him.

Policing techniques required immediate reconsideration in the wake of the High Court’s decision in the Smith case, and other Aboriginal men who had been convicted of bank robbery using the same method had their convictions quashed and re-trials ordered, beginning with Guy Gardner.5 The ramifications of the High Court’s decision continued into February 2004 when Redfern erupted into a ‘riot’ following the death of a teenage Aboriginal boy, T J Hickey, during a police pursuit. As indigenous youth clashed with police late into the night, police and amateur footage was taken, and later used to identify some of the participants. The Police Minister John Watkins issued a media statement confirming that the High Court’s decision in Smith v R would not impede the swift and strenuous pursuit of trouble-makers (Watkins, 2004). He said that, following the riot, the Police Commissioner Ken Moroney had sought legal advice which:

confirms the Smith case cannot be used as authority to exclude images which depict an offence being committed. It does not matter whether images come from security cameras, media outlets, or bystanders. The bottom line is – as long as the pictures depict an offence being committed, they are relevant and admissible.(Watkins, 2004)

The Minister was ‘pleased’ with this advice and announced that police would ‘continue their great work at Redfern’, restoring the nation’s fantasies of law and order and children in their beds at night,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword: Alison Young

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Table of cases and documents

- 1 The hooded bandit

- 2 The national bank

- 3 The epidermal examination

- 4 The mother’s trouble

- 5 The danger zone

- 6 The spectre

- 7 Your fantasy, my crime

- Bibliography

- Index