![]()

CHAPTER I

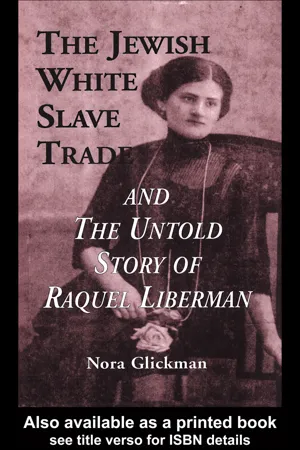

The Jewish White Slave Trade

The Zwi Migdal

Only here there are chimneys of steamers (…) They unload all the elements indispensable for the construction of an immense city giving birth.

Everything!

Only the most important thing is missing… Woman!

Albert Londres The Road to Buenos Ayres

During the first decades of this century there was as yet no law that prohibited public, open prostitution in Argentina. Buenos Aires and its surroundings were swarming with brothels, and the traffickers dealing in that market enjoyed multiple privileges. They had free access to the ports, could climb aboard the arriving boats, and even remove by force those girls who offered any resistance, without facing any struggle from the authorities.

In spite of the fact that the larger number of foreign-born women arrested in Buenos Aires for scandalous behavior were Spanish, French or Italian rather than Eastern European, the persistent reference to Jewish pimps and prostitutes became a sign of religious depravity. Several historians coincide in that prostitution in Argentina was not primarily a Jewish business. The French, who catered to a richer clientele, dominated the vice scene. The Jews, in turn, were followed by the Italians and the Creoles.1

What is remarkable is that public accusations against Jewish delinquents made by Argentine Jews did not have a parallel among other immigrant groups, as those groups did not discriminate against their “own” pimps and prostitutes. This, in fact, in Bernardo Kordon’s estimation, may be regarded as a tribute, as it “testifies to the strong moral zeal that characterized Jews in Argentina and in the rest of the world.”2

Prostitutes were extremely reluctant to testify to the authorities for fear of reprisals from their slavers. The laws protecting minors from the trade were seldom enforced. Traffickers, for their part, did everything in their power to keep their activities secret.

As early as the mid-nineteenth century Domingo F.Sarmiento and Luis Alberdi were advocating policies which encouraged a European immigration that would drastically change the prevailing conditions in Argentina. The majority of the immigrants who came to Argentina were single and married men who were leaving their families in their native countries with the hope of gathering sufficient funds to send for them soon after.

Through previously arranged contracts—such as those of the Jewish Colonization Association—Jewish families from Eastern European countries arrived at the port of Buenos Aires from where they were directed to their farms in the provinces and distributed in the Argentine Pampas. Few of them remained for any length of time in the Capital. The immigrant Jews of this group were called rusos, as most had been born in Russia.

The larger immigrational Jewish group began to arrive in Argentina in 1890. Most of them (over 40,000) were agricultural pioneers brought over under the sponsorship of Baron Hirsch, a Bavarian philanthropist who wished to save them from the Pogroms in Eastern Europe. Baron Hirsch created the Jewish Colonization Association (ICA), to provide them with settlements in their “golden” land of Argentina.

Although Baron Hirsch’s representative warned the new immigrants about the presence of human flesh traffickers outside the gates of the port, and advised them not to let their families into the street, a few families fell into their hands. Mordechai Alpersohn, one of the pioneers who arrived in Argentina as a farmer in 1891, commented that “near the gates of the immigration house [they] met a few dozen elegantly dressed women and fat men in top hats. Through the gates the [procurers] were talking with [the immigrants’] wives and gave chocolate to the children.”3

In spite of the efforts of the ICA, by 1910 Argentina was stained with the image of being a “contaminated land”. And trafficking was identified as a principally Jewish activity, to the point of endangering the potential immigration from Europe.

Perhaps in response to the disproportion of female to male population—a high number of males in relation to a small number of females—commercial vice began to infiltrate Argentina in the late 1880s. The great imbalance also became evident in the demographic disproportion of immigrants to natives living in the country. Since 1889, however, international agreements obliged governments to create agencies to monitor the moves of people exporting women for prostitution into Argentina.

Until 1910 prostitution in Argentina was seen as a morality issue. In response to the pervading fear of dangerous lower class women who sold their sexual favors out of dire poverty, and of those who enjoyed themselves while they earned their “immoral wages,” new morality laws were passed. They required that immigrants pass literacy and medical tests, that they produce a certificate proving they had been free of a criminal record for the previous ten years, and that women under twenty-two could not enter the country alone, unless they were met by a responsible person.4

Although xenophobic sentiments in Argentina were directed against minority groups already living there even before 1880, when the physical presence of the Jew was almost nonexistent in Argentina, certain authors expressed exaggerated fears of the dangerous influence of Jews in their country. As critic Gladys Onega points out in her book La inmigración en la literatura Argentina: 1800–1910, “xenophobia has served in our country…as a pretext for the defense of the most conservative and antisocial values and interests.”5

Anti-immigration conservatives linked the white slave trade with the corruption and debasement of Argentinian morality. They presented a distorted picture of the Jew based on racial prejudice and the prevailing Christian myths derived from Judas and from the Wandering Jew. The early decades of this century witnessed an increase in stereotypes of wealthy bankers (The Rothchilds, the Galeanos, the Bauer and Landawers), and a surge of the publications influenced by anti-Semitic European literature, such as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Edouard Drumont’s La France Juive.6

Politicians and the public openly discriminated against foreigners and legalized prostitution. They heightened their anti-white slavery campaign and attempted to abolish municipally licensed bordellos. Consequently, pimps and prostitutes were forced create their own societies and to conduct their activities surreptitiously, with the connivance of the police, in order to evade new regulations.

CRIMINAL ORGANIZATIONS:

Although to naive minds there was no difference between one criminal Jewish group and another, during the first three decades of the twentieth century, two groups of Jews lived side by side in Buenos Aires: The “pure” ones, and the t’meyim (Hebrew for “unclean”). The traffickers insisted on identifying themselves as Jews, and on legitimizing their religion through rites. This was a factor that disturbed the Jewish community intensely, as they feared the possible confusions that might derive from xenophobic and antisemitic actions (Mirelman, 352).7

The paradox consists in that at the same time as the t’meym profess with devotion a religion of high ethical principles, they do not hesitate to practice the commerce of women. A report of the beginning of this century describes their ostentatious lifestyle:

They wear enormous diamonds, they attend the theater or the opera daily. They hold their own clubs, where the ‘merchandise’ is classified, auctioned and sold. They have their own secret code… They feel comfortable in the Jewish neighborhood knowing that many of the tailors, shop-keepers, and jewelers depend on them as clients (Mirelman, 351).

THE “CAFTEN SOCIETY”:

Feeling ostracized from their community the traffickers built their own synagogue to perform the religious ceremonies of their members, and they also built their own cemetery. The Hungarian Jews from Rio de Janeiro were the first to manage a “Caften Society”—so called because their traditionally long gowns became synonymous with pimps in charge of the illegal brothels.

THE “WARSAW SOCIETY” AND THE “ZWI MIGDAL”:

A notorious institution which passed off as a mutual aid provider, was the Warsaw Society, founded in 1906. In 1926 the Polish Ambassador objected to the use of its name and forced it to be changed, as he considered it offensive to his country. The new name the organization adopted was Zwi Migdal after its founding member. Although the numbers vary, it is believed that in 1929 the Zwi Migdal numbered 500 members, that it controlled 2000 prostitution brothels and employed 30,000 women.8 The Zwi Migdal consistently found ways to break morality rules.

THE “ASHQUENAZIM SOCIETY”:

This entity, also associated with the white slave trade, reached its pinnacle of wealth and influence in 1920. It was composed principally by Russian and Rumanian Jews who hid their illegal activities, ostensibly as an Israelite Society of Mutual Help.

THE “POLACAS”:

As early as 1890, when Argentina began to receive large waves of immigration, a large scale commerce of white slaves began to import women from Poland and Hungary. These women, known as polacas were very different from other foreign prostitutes who arrived “in a constant flow from all corners of Europe to Argentina” (Goldar, 48). “Polaca” was the generic name applied to all Jewish prostitutes in Argentina. Violations of the law, widely tolerated by corrupt officials in the customs office, facilitated their illegal entry into the country, and their spreading throughout the city of Buenos Aires.

The polacas were deceived by Jews of good economic standing that came to their native villages to ask for their hand in marriage. Sometimes the girls were visited by suppliers who made “contracts” which were in fact stratagems to raise the hopes of the parents, whose wish was that their virgin daughters would keep their religion and marry men who would provide them with a respectable life—even if it was in such a remote place as Buenos Aires. The parents candidly accepted the false promises from the Alfonsos (traffickers), and gave away their adolescent daughters to their “husbands”, hoping that after a few years they would join them in a land free from poverty and antisemitism.

In Prostitution and Prejudice Edward Bristow also describes the international ramifications of the Jewish white slave trade in Argentina—“El dorado” dream of European traffickers.9 What the polacas had left in their native country was only misery and persecution. Upon arriving in Argentina, however, most polacas encountered new difficulties that, paradoxically, precluded for them any possibility to adapt themselves to the country. But as opposed to the rest of European women practicing prostitution, the polacas soon found they did not have a place to return to, so that they had no other choice but to become an integral part of their community in Buenos Aires.

In response to the total rejection of their community, the traffickers consolidated their efforts to fund their own organizations. The acclaimed Yiddish author Leib Malach—an immigrant from Poland—reports both in journalistic entries and in his fiction how persistently the prostitutes and the traffickers had insisted on attending the synagogue of the Jewish community, and on being allowed to be buried in its Jewish cemetery.10 Upon their rejection, their vast earnings allowed them to build their own temple and burial ground without much difficulty.

In his study on this subject, Victor Mirelman writes about the celebration of the shtile hoopes (“silent weddings”) in Buenos Aires under the auspices of the Zwi Migdal. These ceremonies were not preceded by a Civil marriage, as the Argentine law prescribed.11 In this manner the women were pushed into a miserable existence. Later they would be exploited or sold in private auctions arranged by the traffickers.

The Zwi Migdal also acquired a ceme...