![]()

Women’s Territory

Community and the Ethic of Care at Julie’s International Salon

She has women friends here who will neither let her starve nor weep.

—E. M. Broner, A Weave of Women

Julie’s International Salon—Julie’s, for short—is located in a residential neighborhood of a large midwestern city. More precisely, it is to be found in a nondescript mini shopping strip at the intersection of two busy streets. A large picture window sports the shop’s name, along with hair-design posters, which are tastefully displayed and infrequently changed. Not uncommonly, hand-written signs, posted on the window or the glass door, note changes in shop hours; they decidedly convey an air of informality to the place. Moving indoors, the customer first steps into a rectangular reception area. To the left of the entrance is the shop’s desk; it serves as a cashier’s station and is not regularly staffed. It is usually Helen, who is in charge of hair washing and general shop upkeep, who transacts payments behind the desk. On a wooden surface over the desk, a pen is attached to a chain for the convenience of customers writing checks. Salon pocket calendars often rest sloppily on this surface for the taking. Several chairs are arranged haphazardly near a television set. Two walls are lined with wood-grained, glass-faced cabinets that display various kinds of merchandise for sale, including custom jewelry and women’s clothing. Some of this merchandise has remained in place for years and looks rather shabby for wear. A small room to the right of the entrance functions as a coatroom.

Customers arrive at Julie’s in various ways. Many drive their own cars, which they park in the shopping strip’s parking lot, within view of the beauty shop. Some are dropped off by husbands, or more rarely, by children or friends. A few walk from their homes in the vicinity of the salon. Still others take cabs. On occasion a woman on a wheelchair or a walker is brought in by a companion, or a very elderly, frail woman is helped to negotiate her way into the heart of the shop.

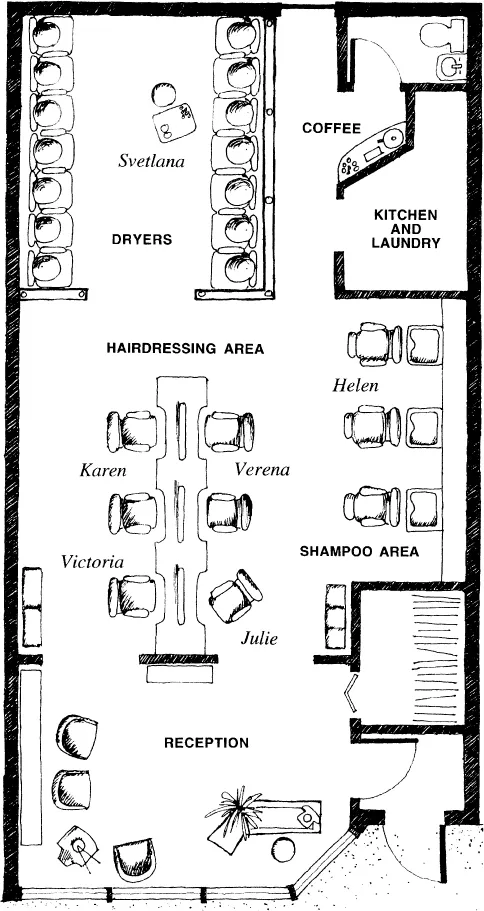

The “inside” area is partly painted and partly wall-papered in soft colors—pink and gray. This area is longitudinally divided by a long wooden cabinet used to support three large, two-sided mirrors and store beauty supplies and equipment. Three cosmetology chairs are located on either side of the cabinet. There are spaces between the mirrors that allow beauticians and customers to see and talk to each other across the division separating the stations. Three hair washing stations, consisting of a chair and a wash basin each, are situated against one wall. Usually only one of these stations is used for its designed purpose. There is also a small bench against the wall behind Julie’s station, which one first encounters after entering the shop. A similar bench resides behind Victoria’s station, immediately opposite Julie’s on the other side of the room divide. These benches and chairs provide opportunities for socializing while customers await their turns.

The back part of the shop, beyond the main “inside” room, consists of a large area lined on opposite sides by old-fashioned hair driers—fourteen in all—the type used to dry hair set in rollers by placing a kind of helmet over the head and adjusting the heat to personal comfort. It is in this area that Svetlana, the manicurist, works, using a portable cart that holds her supplies and provides a working surface. A small kitchen and a bathroom are connected by a small corridor, in which is located a coffee station: coffee pot, cups, and virtually always sweets to eat.

The interior’s accent is on functionality, not glamour. In fact, the place is characterized by homeliness and an unkempt flavor: It is not unusual to see hair curlers or towels on the floor, for the TV to be blaring even when no one is watching, and for people to be yelling from one part of the shop to the other. These very characteristics may in fact facilitate the communal nature of social interaction there, as the sociologist Ray Oldenburg argues in The Great Good Place, where he studies coffee shops, taverns, and cafés—neighborhood places where people used to hang out, away from both home and work. According to Oldenburg, these features discourage pretension among those who gather there, thereby encouraging social leveling1 and hence an atmosphere conducive to friendliness and social exchange.

Adding to the shop’s informality is the occasional presence of staff members’ children “hanging around” during school holidays. Julie’s three children typically occupy the reception area during these times. Victoria’s oldest son watches television when he comes in with his mother on Saturdays. Customers delight in and fuss over the children, who are never perceived as a nuisance in this context, even when they run around the shop or raise their voices in gleeful play or discord. Informality is also reflected in the self-presentation of customers when they come to the shop. Many are very casually dressed and wear no makeup at all.

Julie’s International Salon. Drawing by Dianne Hanau-Strain.

In the past, the neighborhood was characterized by a heavily Jewish population. While the neighborhood is more mixed than it was some twenty years ago, the older population is still predominantly Jewish (there is currently an influx of young Orthodox families into the area). The salon’s clientele is mostly drawn from the neighborhood. It is largely female, American-born, middle-class, older, and Jewish. Not all Jewish customers are of the same stripe, however. They range from those involved in some branch of religious Judaism, to those active in the local Jewish Community Center, to women who have no formal connection to any Jewish institution yet have strong Jewish identities. For most customers that identity appears to be shaped by ethnic rather than religious meanings, in keeping with similar patterns generally observed among second-generation Jews.

In a real sense the shop follows the Jewish calendar, as major Jewish holidays are marked by appropriate decorations throughout the year. The shop closes on Yom Kippur and displays a lit electric menorah on the window during Hanukkah. Women freely offer each other holiday greetings. Speech is frequently sprinkled with Yiddishisms when Jewish customers speak together. Discussion of holiday foods and family dinners is frequent. Food brought into the shop for sharing often is “Jewish style.”

The salon staff is non-Jewish (save for the manicurist) and foreign-born: Korean, German, Russian, Greek. It is also exclusively female. As a consequence, the shop constitutes an all-female space wherein it is rare to see men at all. Occasionally men come in, usually to pick up their wives, in which case they wait in the reception area, behind an invisible border that separates it from the “inside” of the salon, where the “action” is. On rare occasions men do enter this “inner sanctum.” I am told that a few men are customers, although I have never seen one in that role in all the years of my visits as customer or researcher. Some men occasionally come into this space to chat briefly with a spouse or parent, in which case they are most commonly ignored, that is, rendered invisible. In short, this is principally “women’s territory.”2 In this regard Julie’s is an old-fashioned shop since unisex hair salons, which serve women and men and are typically staffed by both sexes, are now the norm. Julie’s also continues to offer certain services largely unavailable in today’s typical salon, namely, hair setting. It is common to see here, but not elsewhere, women getting their hair set in rollers and then sitting under hair driers before being “combed out.”

To the untrained eye, customers might look alike, reflecting the tendency to homogenize the Other—in this case, older Jewish women. But if you spend any time at Julie’s you notice that, like anyone else, each woman has a unique personality and presents a distinct public persona. What they share is an unprepossessing yet unmistakable presence that seems to announce, “Here I am.”

The Salon as Community

By now it should be clear that in no way is this an upscale salon. According to Marny, a long-term customer, this is a “good, old-fashioned beauty shop. I don’t know if there are many left. There are a million of the ‘la-la-la’ salons downtown and in the suburbs; and they put up high prices and high names.… What’s different about Julie’s is there is no pretense.… What you see is what you get.” Lucy, an affluent customer who commutes a fair distance to Julie’s, suggests that the run-down nature of the place is “comfortable for the haves and it’s comfortable for the have-nots. And there’s plenty of haves there.… It’s a real melting pot.”

Whereas for Lucy the attraction of Julie’s is its socio-economic variety, for Edie the pull is its cultural diversity, the fact that the staff is multinational: “Julie’s is an international beauty shop. Did you know? … It’s beautiful. And we all get together. We all like each other.… We get along beautiful. You go to a different beauty shop, you have to sit there and nobody is talking to nobody.”

A similar note is struck by Anna, who, as we will see, is a Thursday customer who takes charge of bringing food to the beauty shop for everyone’s consumption. She tells me, “We have a very international organization: Julie being Korean; Verena being German; Helen is Greek; Svetlana is Russian; the other girl, Victoria, is Greek; Karen is an American; and I’m Jewish.3 All of this melds together. We have no problem with it. So it’s very international. To watch Julie eat Jewish food is hysterical. She loves it!”

The fact that the staff is foreign-born—save for one beautician, Karen, who only works on Saturdays—contributes to rather than detracts from the communal ethos at the beauty shop. This is because these women—all substantially younger than their clientele—share some fundamental values with their customers. These include a central commitment to family, conservative cultural values, and an appreciation for the value and experience of old age. By American standards, these workers reveal values of an older generation—hence the fine fit with their customers.

In an effort to articulate the meaning of community for modern people, Martin Buber wrote,

Community … declares itself primarily in the common and active management of what it has in common, and without this it cannot exist…. The real essence of community is to be found in the fact—manifest or otherwise—that it has a centre. The real beginning of a community is when its members have a common relation to the centre overriding all other relations.4

Buber refers here to what might be called an intentional community—people purposefully drawn together by a core set of concerns. Here I argue that community at Julie’s is of an unintentional sort: Without planning or design, Julie’s emerges as a group of individuals—a different group depending on which day of the week their appointments fall—who enter into ongoing relations with one another around a shared set of concerns. Narrative theologians suggest that community is constituted by those people who share stories, stories with a mythic and symbolic depth emerging from the past that speak to people’s contemporary experiences.5 I believe a variation of this sort of storytelling takes place at Julie’s that forges this beauty salon into a community.

Community becomes possible among customers for a variety of reasons, including the casual style of the physical environment already described, but also because of shared structural commonalities, including age, gender, ethnicity, and in many cases, marital status, since virtually all customers are either married or widowed. The stories women tell, though seldom of a religious or mythic nature, draw them into shared universes of meaning. The stories, as we will see in this and other chapters, relate to the experience of being female in a society that demands the display of a feminine appearance; the reality of aging and physical decline; the history of many customers as second- or third-generation American Jews; their background as mothers and homemakers, caregivers par excellence. Storytelling is complemented by action, so the salon becomes a site for the performance of caring deeds, as well.

Despite the values shared by the staff and clientele and the latter’s appreciation of diversity, there are some built-in tensions between customers and staff tied to their respective roles. A customer, after all, is an employer of sorts, a beautician or manicurist an employee. These power inequalities surface on occasion. During “slow” days, for example, when bad weather keeps customers away, Svetlana shows me her appointment book, anxious about the number of customers she can count on for the day. In this way she reveals her economic dependence on her regular clientele. Julie often shares her frustrations with me about difficult customers: those who routinely arrive late, those who rush her, those who make unreasonable demands, those who dislike one another and use her as an intermediary. Verena is more spontaneous about expressing her aggravations directly and sometimes wrangles with some customers. But I also observe that she seems to get along very well with many of her customers. “I like more than I dislike,” she says, adding that she simply ignores difficult customers, stays quiet, and does her job. Julie confides that despite the stress that some people and situations engender, when she’s away from the shop for a day she misses it. She appreciates the close ties she has with many customers, recognizing their unusual nature in a work setting. If friendship and community emerge from relationships among equals, then the communal life at Julie’s is centrally a phenomenon experienced by the shop’s clientele. What is significant at Julie’s is that despite the power inequalities between customers and staff, as we will see, staff members frequently partake in communal life and find areas of reciprocal sharing with many customers.

In chapter 2, I will discuss at some length what motivates customers to frequent beauty salons. Here I turn to a more specific question, namely, why they choose to patronize Julie’s International Salon, in particular. We should keep in mind that most customers have standing weekly appointments; most also have a long-standing relationship with this particular beauty shop, in some cases antedating by many years its 1982 purchase by Julie.

A few customers cite convenience as the key reason for going to Julie’s. These are women who live in the immediate neighborhood and walk to the salon or get there via a short car ride. This is not a sufficient reason, however, as there are other shops in the general area that could command their patronage. For these and other women, the competence and efficiency of their beautician is a real draw. In the case of two beauticians, Verena and Victoria, many customers followed them from other shops years ago. Women laud not only the work of their beauticians, but also the fact that these are nice people, people they have grown fond of, people who care about them. Edie celebrates the fact that “Victoria and I get along so beautiful.” Referring to Verena, a woman tells me, “She’s good. She listens to you, she sympathizes, she talks, she laughs at you, she makes fun at you.” In short, she is attentive. Customers frequently cite their affection for Helen, the “shampoo girl,” who always has a kind word for everyone. As Teri sees it, “Helen greets you like you’re a long-lost relative.”

Julie, the owner of the shop, is the object of greatest admiration because she is seen, not only as a capable beautician, but as the tone-setter for the salon. And it is the shop environment that seems central to customers’ enjoyment of the place and their desire to continue their association with it. People characteristically mention Julie’s warm personality and calm demeanor. She is seen as “a kind, delightful woman”; a “sweet girl—she’s got the patience of a saint”; a “hard-working, nice girl”; a “good person”; “friendly, pleasant”; “very accommodating.” One woman tells me that Julie is “very nice. I feel she has a Jewish heart,” that is, Julie is able to bridge their ethnic differences. Julie is also seen as a capable manager since there is no tension evident among the staff, a situation commonly reported about other beauty salons. Many women also value Julie’s insofar as there is seldom any bickering among customers as is usual elsewhere: “Nobody gets on anybody else’s nerves,” says Anna. “Nobody is hollering, ‘Me first,’ which is horrible.” Perhaps Martha best captures shared perceptions when she declares that Julie “creates a very warm, accepting atmosphere, and people who are there respond in kind.”

Anna says that Julie’s is “like family … like a second family to many women,” a sentiment echoed by other customers and staff, as well. Reva calls it “family-style,” while Martha suggests that “It’s a friendly, homelike atmosphere. You become part of the family.” Some customers, though not the majority, are in fact integrated into Julie’s family, at least in symbolic terms. Martha recounts occasions she and her husband were invited to celebrate Julie’s family events, including a baby shower, a birthday party, an open house, a wedding: “My husband and I got to know her whole family.” Apparently a few other salon customers were also guests at some of these happenings. Another case in point is a customer named Pam. When Pam arrives for her usual Thursday appointment one December morning, she is thrilled to see Ceci, Julie’s youngest daughter. She takes Ceci into her arms, kisses her on the lips, and asks Julie why “Grandma Pam” wasn’t told Ceci would be there. The child and the older woman spend some intimate time together. On another occasion, as Pam leaves the shop, she tells Julie, “Tell my little girl I love her.”

Images of home also are repea...