![]()

Part I

GIRL TALK

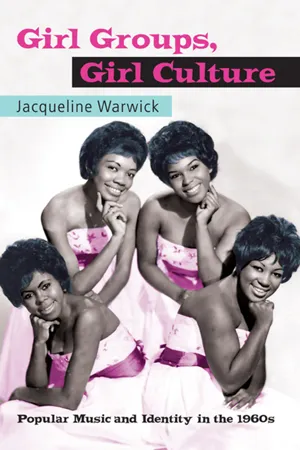

A founding member of the Supremes, the most successful and well-known female vocal ensemble of all time, Mary Wilson has published a best-selling memoir recounting the trajectory of a career that emerged against the backdrop of the girl group phenomenon of the early 1960s.1 At one point, she recalls indignantly that at the height of the Supremes’ commercial success, some considered the three singers to have lost their inherent black “soulfulness,” to the point that a British journalist even urged them to “Get back to church, baby!” In fact, none of the Supremes had ever sung in church, and Wilson complains about “the misguided notion that a black who was singing and didn’t sound like Aretha Franklin or Otis Redding must have been corrupted in some way.”2 As I will show in this section, the girl group sound developed by drawing on many musical styles, of which gospel singing was by no means the only one, or even the most important. I want above all to refute still-widespread assumptions that black singers of soul, R&B, and rock’n’roll all draw on some instinctive, intuitive vocal ability that is simply a by-product of their genetic makeup, rather than a learned artistry requiring considerable skill and effort. My discussion considers the still-developing adolescent voices in girl groups, the relationships they enacted in their records, and the possibilities they present for an understanding of the Voice of the Girl.

![]()

1

THE EMERGING GIRL GROUP SOUND

With their glamorous gowns, elegant choreography, theatrical vocal style, and songs dealing with adult themes such as marital infidelity (“Stop! In the Name of Love,” 1965), illegitimate children (“Love Child,” 1968), and filial guilt (“Livin’ in Shame,” 1969), the Supremes were in many ways never really a girl group, although they are often named first in a list of girl groups from the 60s. Even their earliest hits, “Where Did Our Love Go?,” “Baby Love,” and “Come See about Me” all appeared in 1964, a year in which the girl group “moment” was, for all intents and purposes, over. The girl group sound and style occupied a prominent position in mainstream popular culture at the very beginning of the 1960s, emerging in 1957 and dominating the pop charts from 1960 to 1963. The style was predicated on the sounds of adolescent female voices audibly going through hormonal development—most girl group singers really were girls, with ages ranging from eleven to eighteen in the most representative groups. Girl group records had lyrics addressing themes of special importance to teenage girls, such as boys, the strictness of parents, and the complexities of imminent womanhood. The genre generally involved young vocalists backed by studio musicians, performing material written by professional songwriters (though this book will present several examples of groups that operated differently). Girl group music was at the forefront of popular music during the early 1960s, an unprecedented instance of teenage girls occupying center stage of mainstream commercial culture. This phenomenon was not repeated until the late 1990s and early twenty-first century, when latter-day girl groups and solo singers including the Spice Girls, Britney Spears, and Avril Lavigne, among others, were immensely successful in bringing girl’s voices and concerns back to prominence in mainstream music.

One of the first ensembles to achieve critical and commercial success as a girl group was the Chantels, who really had sung in church: members of the quintet were Catholic convent school girls from the Bronx who were trained in chant and choral singing. Lead singer Arlene Smith would go on to pursue formal music studies at the Juilliard School, and as teenagers, all group members took lessons in piano, were musically literate, and were adept at close harmony singing, thanks to a steady diet of motets and hymns. The Chantels were the first group of black girl singers to attract a significant following, beginning in 1957, only a year after the eruption of rock’n’roll into mainstream culture. When their career took off, members of the Chantels ranged in age from fourteen to seventeen, and they had been singing together at school for more than seven years.1

The Chantels

There are conflicting accounts of how the Chantels came to prominence. Charlotte Grieg and Alan Betrock, both of whom draw on interviews with Arlene Smith, assert that the group lay in wait backstage at Loew’s Theatre one night for well-established producer/manager Richard Barrett to emerge after an episode of The Alan Freed Show, and then caught his attention by singing either a unison hymn or their own composition “The Plea.”2 Michael Redmond, Steven West, and Jay Warner, on the other hand, state that the group happened to recognize Barrett and his group, the Valentines, walking on Broadway one afternoon and approached them for autographs. Hearing these young girls boast that they were singers, too, Barrett challenged them to sing something then and there; under the awning of the Broadway Theatre, they performed a hymn in Latin and impressed him with their angelic sound.3 In both versions of the story, Barrett was intrigued by the possibilities of blending these choirgirl voices with R&B grooves and doo wop harmonies, and he eventually took the group in hand, cowriting their material with lead singer Arlene Smith, producing their records with George Goldner, and guiding the group to considerable chart success over the next four years.

The voices of the Chantels were an exciting sound in 1958, the year their song “Maybe” rose to #15 on the pop charts and #2 on the R&B charts. Their choirgirl diction and the focused, ringing timbres of their upper vocal registers were novel, resembling in some ways the sweet-voiced sounds of urban black teenage boys singing doo wop, and in other ways the barbershop aesthetics of white, mid-Western women like the Chordettes, and even the polished recordings of white, adult starlet/pop singers such as Debbie Reynolds or Patti Page. Their African American identity also invited superficial comparison with blues shouters such as Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker, and Etta James, although the Chantels never emulated a bluesy, gritty vocal style. Ultimately, the Chantels’ music could not be categorized with any other style of the day, and their success spawned many imitators and precipitated a new genre in popular music. However, the girl group sound of the early 60s would develop a markedly different aesthetic from the Chantels’ sound of the late 50s, as even a cursory listening of records by the Shirelles, the Crystals, the Cookies, or the Marvelettes reveals.

The Chantels’ success with “Maybe” paved the way for other girls to enter the world of the music industry, hitherto populated largely by adults and a few teenage boys. “Maybe” set the benchmark for the Chantels and many other female harmony groups. The song is credited variously to Richard Barrett and to Arlene Smith and George Goldner, although Jay Warner asserts that this and many other Chantels songs were composed by Arlene Smith alone and then credited to Barrett and George Goldner—this is, of course, a common claim about many popular songs, particularly in the girl group repertoire.4 Stylistically, “Maybe” closely resembles songs credited solely to Smith such as “He’s Gone” and “The Plea” (both 1957). These songs make use of close harmony singing, featuring Smith’s full and impassioned sound supported by the comforting tones of her sister Chantels. In “The Plea” the protagonist begs forlornly for her lover to remain at her side, while in “Maybe” she yearns for his return—in both songs, she prays ardently for the return of her affections, a religious allusion also present in “Every Night (I Pray)” and “Prayee” (both 1958).

Based on song titles and lyrics alone, these songs reinforce the seldom-examined assumptions that all young African American singers at mid-century were heavily steeped in gospel music traditions and that vocal ensembles like the Chantels came together through singing in black Pentecostal churches. The dialogic style typical of what would be called the girl group sound is assumed to derive from the singers’ musical education of rote learning with call and response, building songs through collective improvisation from a shared vocabulary of memorized riffs, with careful reaction to a leader’s spontaneous singing, which is in turn dictated by congregational behavior. This mistaken belief often led white music critics in the late 1960s to condemn girl groups and other African American acts erroneously for abandoning their gospel roots and “selling out,” as Mary Wilson recalls on page 11. Further confounding this simplistic assessment, the Blossoms, a Los Angeles trio who became emblematic of girl groups because of their position as regular backing singers on the popular television variety show Shindig!, comprised members raised in very different liturgical traditions. Darlene Love was a preacher’s daughter brought up in the Pentecostal Church of God in Jesus, whose father was so displeased by her singing secular music that she was forced to leave home at an early age; Jean King grew up singing chant in the Roman Catholic tradition; and Fanita James was raised in the Methodist church by a father who was a jubilee singer.5

The Chantels met at choir practice in the Bronx, but rehearsals were led by a nun at their Roman Catholic convent school, St. Anthony of Padua.6 Indeed, the choral influence was so strong that, according to composer Arlene Smith, “The Plea” was based on Gregorian chant.7 Some features of the melody do suggest the influence of chant; for example, the melody is centered around a repeated pitch that is a fifth higher than the final resting place of the tune. This is similar to the function of a reciting tone in chant repertoire, in which most of the text is sung on a single repeated pitch a fourth or fifth above the final.8 Furthermore, the melodies of “Maybe” and “The Plea” are grounded in a high tessitura that is unusual for pop songs, and they feature tutored choirgirl diction—Smith’s “ee” vowels in particular are more in line with choral pronunciation than with American conversational English. Her controlled vibrato with lowered larynx is not typical of the straight, vibrato-less sound favored by most choral directors, but it is strikingly different from gospel and blues singing styles and suggests that her vocal training was at least in part focused on singing solo with classical technique. Smith recalls the musical education of the Chantels:

When I was about seven I became a member of the St. Anthony of Padua Cherub Choir. We were all trained in music from a very early age; we all took piano and voice lessons from the same nun. By about ’53 or ’54, just as we were coming up to our teens, we started to be interested in pop—and boys, of course. At that time I played basketball because I was tall. I was second string so I had a chance to sit on the bench and fool around with my friends. We grouped together and sang; and a sound kept evolving.9

A picture of nicely brought up convent schoolgirls singing together while under supervision at school activities suggests that the soundscape of the Chantels’ world did not include the aggressive, raw sounds of jump blues or R&B and that the pop music Smith was interested in probably comprised mainstream Tin Pan Alley standards. Similarly, Mary Wilson insists that

[the Supremes’] roots were in American music—everything from rock to show tunes—and always had been. We weren’t recording [Tin Pan Alley] standards because they were foisted on us by Motown; we loved doing them and had since we were fourteen years old.10

The close harmony style of Chantels recordings also evokes barbershop quartet singing, and “The Plea” in particular features many hallmarks of the barbershop sound: liberally used seventh chords; echo effects at the end of verses, resembling the classic “Sweet Adeline”; and a vocal arrangement that places the lead singer second from the top, with a higher voice contributing to the backing vocals, in a style standardized by the Andrews Sisters and other vocal harmony groups in the 1940s.

Close Harmony Singing: Barbershop

With regard to female singing groups in the 50s, this distribution of vocal parts typifies the work of the Chordettes, a quartet of young white women from Wisconsin whose hits include 1954’s “Mr. Sandman,” “Eddie my Love” in 1956, and 1958’s “Lollipop” (by teenage songwriter Beverly Ross, a Jewish New Yorker who would go on to cowrite Lesley Gore’s “Judy’s Turn to Cry” and several other 1960s hits). The Chordettes were explicitly linked to the barbershop genre; their founder Jinny Lockard was the daughter of a president of the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America (SPEBSQSA). Following barbershop nomenclature, they described their voices as tenor, baritone, and bass rather than using more customary terms such as soprano or alto for females in choral music. The Chordettes’ nimble voices and ringing harmonies were enormously popular to adult and adolescent listeners alike in the post-war era, but their appeal became more limited after the rise of teen genres in the late 1950s; although they embraced rock’n’roll more enthusiastically than many of their peers, their sound and image connected them strongly to ideas of young suburban wives in Middle America.

The possibility that African American girls in the Bronx might have been influenced by barbershop singing might seem farfetched; this genre is commonly understood as the province of fresh-faced, white, male singers from Smalltown USA, thanks largely to cultural texts such as Norman Rockwell’s illustrations of barbershop quartets in the 1920s and 30s, and Meredith Willson’s 1957 Broadway musical The Music Man, made into a popular Hollywood film in 1962. The sounds that we now think of as barbershop were, however, a significant feature of black quartet singing in the late nineteenth century, well documented in newspaper accounts and reviews from the period.11 Gage Averill argues that in American vernacular culture, “close harmony [singing is] a music of racial encounter, of a profound cultural intimacy, a short circuit in the hardwiring of racial separation and segregation, and the product of cultural transgressions, borrowings, mimicry, miscegenation, and cross-cultural homage.”12 Averill’s notion of close harmony singing as an overlooked ancestor of rock’n’roll history is crucial to an examination of the girl group genre. I want also to follow his example in my consideration of the racial encounters involved in girl group music, arguing that notions of Girl Identity derive from multiple race and class origins, just as songs like “The Plea” and “Maybe” are shaped by numerous musical traditions.

Close Harmony Singing: Doo Wop

Jeffrey Melnick makes a similar case for doo wop, arguing for a nuanced understanding of racial encounter in this vocal genre: “How do we come to terms with the ‘black’ music made by Lee Andrews and The Hearts if we admit that its guiding imagery comes from the Shakespeare they learned in school? What if some African American teenagers turn out to have been a lot like some white ones, especially in their expressive practices?”13

The Chantels’ “Maybe” makes skillful use of the vocabulary of doo wop songs: a 12/8 meter; a looping, descending harmonic pattern of I–vi–IV–V, the “doo wop progression” that characterizes such songs as Gene Chandler/the Dukays’ 1962 “Duke of Earl” and “Heart and Soul” (a favorite with amateur pianists since the 1930s); and fervent singing about love lost. After an introduction of Fats Domino–styled triplets in the piano and voices on “ah” vowels establishing B-flat major, Arlene Smith sings a melody built on a stepwise descent, pondering that “maybe if I pray every night/you’ll come back to me.” At the end of this phrase, the harmonic framework has cycled through the doo wop progression to F major, the dominant, denying Smith the closure she seeks through her lyrics. She must repeat her melodic phrase insistently, enacting the wishful thinking that is her song’s theme as she strives for the comfort of the tonic. At the end of each verse, as she contemplates the possible reciprocity of her love, the other Chantels mirror her sentiments with a barbershop-style echo: maybe, maybe, maybe.

Smith’s high soprano (the entire range of “Maybe” sits on the top half of the staff, an unusual sound in pop singing) is in many ways like the falsetto virtuosity of groups such as the Platters (“Only You”), the Crests (“Sixteen Candles”), and, above all, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers (“Why Do Fools Fall in Love?”), whose influence on the girl groups was significant. In her autobiography, no less a girl group icon than Ronnie Spector identifies Lymon as...