![]()

Part I

Repositionings

![]()

1

The problematics of print

A tale of two cities

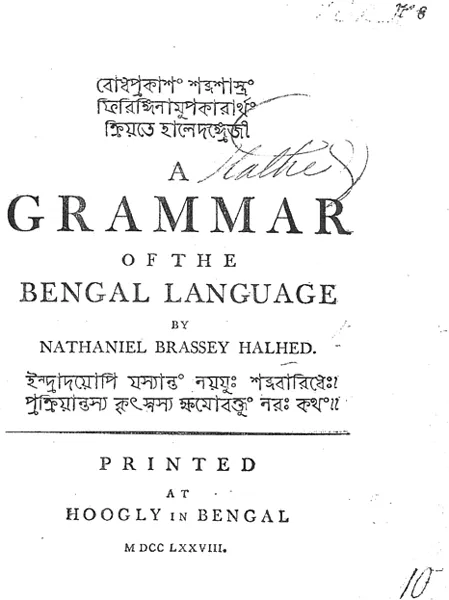

Were you to sit amid the faded Georgian splendour of the Asiatic Society in Kolkata, or else amid the austere postmodern architecture of the Rare Books Room of the British Library in London, you might well find yourself staring at the very same page. The quarto volume that contains it is quite slender – a mere 216 pages of main text with 30 pages of prelims – but it could scarcely be of greater interest. What you would be looking at in either city is the title page of the very first book in the world to employ moveable Bangla – that is Bengali – type. A Grammar of the Bengal Language was compiled at Hoogly (by the banks of the Hoogly river in present-day Kolkata) in 1778 by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, a twenty-seven-year-old ‘writer’ or probationer clerk in the East India Company. Halhed has signed the page near the top, so that the tail of the ‘d’ at the end of his surname curls across the first block of Bangla characters. That twin copies of his work can yield similar sensations in time zones set five and a half hours apart may seem slightly uncanny. In Kolkata you would need to shut your ears to the traffic in Park Street alongside the building, in London to amicable blandishments issuing from the Tannoy above your head. But lift the tome before you to eye level, and in either location you would notice, just beneath that trailing ‘d’, tiny indentations biting into the coarse, yellowing paper.

Considering the fact that two and a quarter centuries have passed since the book appeared, it is surprising how much has been learned about these marks. They were made by a font designed by Charles Wilkins, an accomplished linguist and writer to the Company, and cast by Panchanana Karmakara, local pandit, blacksmith and descendant of a long line of calligraphers and metallurgists. The expense of turning out both the typeface and the volume – 30,000 rupees, as Halhed’s biographer tells us (Rocher, 1983:76) – was met by Warren Hastings, Governor-General of British India, who then claimed reimbursement from the Directors.

This was evidently a collaborative publishing enterprise, and the people involved had diverse though intersecting careers. Karmakara the technician, for example, had grown up in Triveni in nearby Hooghli. Within a year of finishing work on Halhed’s Grammar he was to be appointed as one of the Company’s official print technicians. At the turn of the century he would join a famous press established by the Baptist Missionary Society in Danish-administered Serampore (Srirampur), fourteen miles upstream from Calcutta, where he would set up and oversee its type-foundry. There he evolved two different – and increasingly sophisticated – Bangla fonts for use in translations of the Bible, and a font in Devanagari – the script in which Sanskrit and Hindi are commonly written – employing 700 different ‘sorts’ or characters. Karmakara is also credited with the creation of fonts in Arabic, Persian, Marathi, Telegu, Burmese, Chinese and seven other tongues. He died in 1804, to be succeeded at Serampore by his son-in-law, Manohara, who would remain there for forty productive years (Ross, 1999:46).

In the meantime Halhed had returned to England, where he became a Member of Parliament and took up residence in Charles Street, Mayfair. In 1785 Wilkins would publish an English translation of the Bhagavad Gita, one of the classics of Hindu spirituality. The translation would carry a Preface by Hastings dated 4 October 1784, and two years later both were translated into French. After adopting (and possibly fathering) a son by Jane Austen’s aunt Philadelphia, Hastings himself would be called back to Britain, where – partly as a result of revelations by the then nascent Calcutta English-language press – he was notoriously to be impeached for corruption in 1788.

The Wilkins Bhagavad Gita was published in London, Halhed’s Grammar in Calcutta but, partly because the decisions of the Company were minuted in India, we know a lot more about the production of the second. During the monsoon of 1778 it was run off on loose sheets in an edition of 1,000 copies. Five hundred sets were held for distribution in India once they had been bound, an operation which the printer advised the bookseller to delay for several months until the dry season. The Asiatic Society’s copy seems to have been presented by Hastings himself. (His slightly grubby portrait in oils hangs in the library lobby just above the lockers and, as you deposit your belongings there at the beginning of a day’s archival work, before him you must bow.) Twenty-five of the remaining sets were mailed to Halhed in Cape Town, where he was putting up for a few weeks on his way back to England (Rocher, 1983:75). The remainder were shipped direct to London, followed later by two pages of errata that were to be bound in immediately after the Preface, together with an additional erratum slip Halhed himself had since added.

If the title page and printer’s instructions tell you something about the book’s production, Halhed’s Preface discloses its purpose:

The language is confident, but it is also slightly ambiguous. The power relations invoked, for one thing, are quite explicit. The English will ‘command’, and the Bengalis will ‘obey’. Yet it is the British who are described as ‘natives’, and in the process of learning a foreign language they are compared to the ancient Romans, who, whilst doing the equivalent, were once ‘civilized’ by the Greeks. Perhaps the most expressive phrase describes the process of assimilating Bengali, presented as an act of direct, politically motivated ‘acquisition’.

Halhed’s primer occupies an iconic place in the print culture of Eastern India, and in 1978 the bicentenary of its publication was celebrated publicly in Calcutta. (It was ignored in England, even in the seaside town of Lymington in the New Forest Halhed had represented as MP, having purchased the then pocket borough for £114 4s 5d.) And certainly, from a postcolonial vantage point, it may seem as if the publication of Halhed’s Grammar was a decisive historical event. It represented, after all, the first primer printed on Asian soil for one of the most widely used languages on earth, spoken now by two hundred million people, the language of the literary polymath Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), and the poets Jibanananda Das (1899–1954) and Buddhadev Bhose (1908–74), the language in which the texts of the national anthems of both Bangladesh and India were both initially written, even if the latter is sung in Hindi translation. Undeniably, too, the book involved at the time a substantial advance in non-Western typography. The only previous attempt to print some sort of Bengali grammar and dictionary had been made in Lisbon thirty-five years earlier. But its compiler, an Augustinian monk called Fr Manuel de Assumpção, had been forced to transliterate everything into Roman type. This had the advantage of highlighting lexical affinities between Indo-European elements in Bengali and de Assumpção’s own Portuguese (on page 592 the Bengali for dente or tooth, for example, is given as dant or dont). But Bengali is a syllabic rather than an alphabetical language, and this early attempt had proved wildly inaccurate. Later, the British printer William Bolts acquired a copy (BL 16741) for 7s 6d, and on that basis attempted to learn the language and contrive his own Bangla font. This experiment had been, in Halhed’s words later, an ‘egregious’ failure (Ross, 1999:78). After making a nuisance of himself for six years, Bolts was deported from Bengal.

So Halhed, Wilkins and Karmakara with their purpose-made Bangla type represented a vast improvement. The question they pose for us is this: did their book, and the many others printed in Indian typefaces in the decades that followed, represent a mere technical advance, or did they also, as some have insisted, involve a fundamental shift, even a revolution, in South Asian culture? It is not difficult to adduce arguments in support of the second, more dramatic, view. Two years after the American Declaration of Independence, eleven before the French Revolution, here apparently was a revolution-in-the-making of an equally formidable kind: the exporting of the European Enlightenment, the commodification of a language, the introduction to the east coast of India of a transforming technology of textual reproduction, even arguably the onset of ‘Modernity’ itself. Print history in South Asia, broken and intermittent before, can be traced in a continuous line from experiments such as Halhed’s, Wilkins’s and Karmakara’s in late eighteenth-century Bengal. The resulting transformation in modes of communication seemingly gave rise, not simply to instructional treatises such as theirs, but to the ‘publication’ of sacred books in myriads of traditions, and the issuing of newspapers in very many languages from centres all over India. It enabled the dissemination of multiplying literary and academic genres, and of scholarly journals and monographs, across great distances. It even – so this argument might run – eventually gave rise to today’s burgeoning and global artistic, political and scientific scene. Looking further ahead, one might – if so minded – attribute to the influence of these events two and a quarter centuries ago recent trends such as the emergence of the subcontinent as an international location for out-sourced printing, or the indispensable place South Asia has come to assume in the matrix of world communications.

The purpose of this and the next chapter is to investigate such claims and, with them, the problematic position occupied by the technology of print in the deep history of postcolonial cultures.

Ex Africa semper aliquid novi

One person who seems to have been convinced of the transforming potential of print for his own culture was a Setswana neighbour of the Protestant missionary Robert Moffat (1795–1883) in Kuruman, South Africa. In 1831, fifty-three years after – and 6,000 miles to the southwest of – Halhed’s and Karmakara’s experiments in Bengal, he was shown a page that Moffat’s assistant Samuel Edwards had just run off on a wooden hand press. The press had newly been acquired in Cape Town, transported upcountry by wagon, and promptly dubbed by the locals ‘Segatisho’ (literally a sharp impression). The neighbour’s reactions were observed by Moffat himself, who recorded that he

‘Segatisho’ is now in the museum at Kuruman, and is still occasionally used. Moffat and his wife had brought her up that very year along with some boxes of (Roman) type and a supply of paper and ink donated by the British and Foreign Bible Society. Soon they were putting her to good use printing parts of the Old Testament in Setswana, followed in 1848 by Moffat’s own translation of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, the first full prose text completed at the mission. Entitled Loeto Loa ga Mokereseti (Christian’s Journey), this is the earliest version of Bunyan’s classic in any language of mainland Africa, although in 1835 a translation had been made on the island of Madagascar (see p. 109 below) and printed in Malagasy using Roman type.

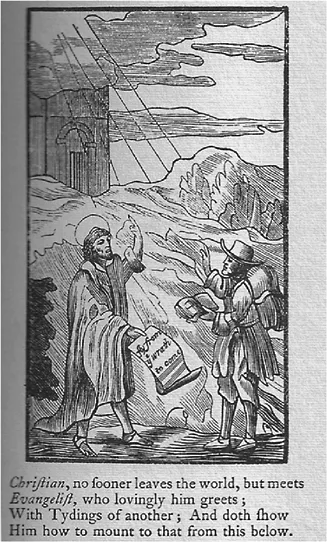

There is, however, an important distinction to be drawn between the Malagasy Pilgrim and Moffat’s, one that can perhaps best be explained by taking a look at a scene near the beginning of the book where, just before setting out on his travels, ‘Christian’ encounters ‘Evangelist’. Bunyan’s own intentions may be glimpsed in a woodcut accompanying the third English edition of 1688 in which Evangelist holds a parchment scroll and Christian clutches a printed book, while the two men absorbedly talk and point towards the sky. Four varieties of human communication – speech, gesture, script and print – are thus brought together in one image (Figure 1.2). Now by 1835 Malagasy had been written for many centuries in Arabic script. Setswana, on the other hand, had needed to be supplied with a provisional writing system before any text could be printed. So, whereas the translators in Madagascar had at their disposal ready-made terms for both writing and reading as well as speaking and signing (even if they had freshly to transliterate them into Roman letters), Moffat was obliged to

convey the former activities by adapting and extending existing vocabulary in a language that possessed no traditional orthography, and could as yet be written only in the somewhat approximate spelling system he and his local informants had been developing since 1826. In her seminal book The Portable Bunyan (2005) Isabel Hofmeyr has granted us an exposition of the significance of Pilgrim’s Progress for cultural identity formation in Africa. It may be useful, however, to spend a moment thinking through the formative role that this classic text, together with other early missionary publications, once played in the very terms in which people came to verbalise modes of textual transmission.

In his translation of Pilgrim Moffat is, for instance, sometimes able to rely on vocabulary his congregation had heard from their Dutch neighbours to the south. When, right at the beginning of Bunyan’s dream, Christian is revealed crying ‘as he read’ his Bible, his book is accordingly referred to with the hybrid term buka. Elsewhere the translator has sometimes had to improvise: the sentence continues mi a buisa mo go coma, mi o rile a buisa a lela: ‘he caused it to speak,...