![]()

Chapter 1

Effective Behaviour Management

Government requirements for initial teacher training courses make clear that all successful students must have demonstrated, in the classroom, their ability to manage pupil behaviour. Newly qualified teachers should as a result be able to establish clear expectations of pupil behaviour and secure appropriate standards of discipline, so as to create and maintain an orderly classroom environment.

Pupil Behaviour and Discipline, DfE Circular 8/94, para. 28.

Like many other areas of work, teaching is riddled with its special jargon. Furthermore, the jargon is constantly changing. In curricular matters, for instance, we now speak of physical ‘education’ rather than, as formerly, physical ‘training’, and we use the term ‘creative writing’ instead of ‘composition’. Children who experience difficulty with the curriculum are no longer ‘backward’ but have ‘special’ or ‘additional’ educational needs, while every primary school must now have a body of ‘governors’ rather than ‘managers’, as previously. The jargon is also changing in matters to do with social behaviour. Traditionally, teachers have talked about ‘controlling’ or ‘disciplining’ children, but nowadays the phrase ‘managing behaviour seems to be more commonly in use.

Although new educational terminology sometimes amounts to little more than new labels for old practices, it often represents a change in underlying assumptions, a redefinition of basic concepts, or a fresh approach. This is certainly the case with the curriculum and administration examples cited above, and it seems true also with respect to the term ‘managing behaviour’. For many teachers today want to distance themselves from the restricted assumptions, aims and practices which are often implied in traditional talk about ‘controlling’ or ‘disciplining’ children. Of course, control is still regarded as playing an important part in regulating social behaviour because children, both for their psychological stability and their group needs, depend upon some measure of direction and a predictable social environment. By itself, however, ‘control’ is too restrictive a concept to do justice to the range of characteristics that contribute to effective behaviour management, while its mechanistic connotations imply that teachers order their charges without respecting their personhood. There is little room for discourse, for listening to and trying to understand the voices of the pupils. The word ‘discipline’ in one sense is importantly associated with ‘disciple’, suggesting that teachers and pupils should be working together towards an idealised kind of behaviour. However, although the term ‘disciplined behaviour’ has this connotation, ‘disciplining children’ is more often associated with ‘disciplinarian’ and notions of inflexible, even harsh, external control.

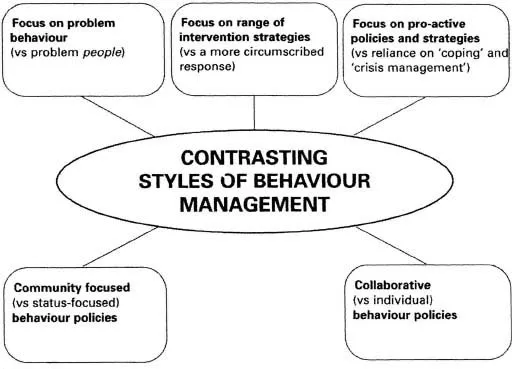

Figure 1.1 indicates five sets of contrasting ideas that characterise the distinction between effective behaviour management (in bold) and controlling or disciplining children (in parentheses). In examining each of these, we shall see how the shift to the expression ‘managing pupil behaviour’ reflects a growing desire amongst teachers to re-examine traditional policies and practices and to develop more positive approaches that are in keeping with recent concepts of good management practice.

Figure 1.1

Focus on problem behaviour vs focus on problem people

The attributional language of staffroom discussions often reveals a good deal about the assumptions teachers hold concerning the cause and nature of pupil behaviour that threatens classroom order. While some teachers personalise the situation by readily talking of ‘problem pupils’ or pupils who are ‘naughty’, ‘disruptive’, ‘disturbed’, ‘devious’, ‘troublemakers’, ‘disaffected’, and so on, others prefer to talk in terms of individuals’ problem behaviour and its effects. The term ‘managing pupil behaviour’ is intended to convey this difference of emphasis by avoiding the suggestion that a child presenting behaviour problems is inherently a problem person. The trouble with using terms which imply the notion of problem people is that we may encourage those to whom we talk to slip into the habit of labelling children negatively, so that everyone no longer sees ‘the child with problems’ so much as the inherently ‘problem pupil’, ‘the disruptive pupil’ or ‘the troublemaker’. For the language we use in describing a situation affects the way we come to conceptualise that situation, and this in turn affects our response to the situation. Too easily, ‘problem people’ becomes ‘those whose behaviour we believe cannot be changed’.

Terms like ‘troublemaker’ and ‘naughty pupil’ tend to characterise problem behaviour as intentionally and malevolently produced. Such terms convey the assumption that children who are thus referred to need only to change their attitude in order to change their behaviour, and that responsibility for this rests with the child. The term ‘disruptive (rather than disrupting) pupil’ conveys similar assumptions. No doubt, the use of these expressions serve as a defence mechanism. For by attributing behaviour problems to the child’s bad motives, teachers preserve their own status by exempting themselves from blame whilst also conveying the message that any change in their response to the behaviour is conditional upon the child taking the first step.

This was demonstrated in a study of four- to eleven-year-olds who presented problems of one kind or another in the classroom. Rohrkemper and Brophy (1983) analysed teachers’ reactions to various types of learning and behaviour problems, including aggression, defiance, shyness, rejection by peers, hyperactivity, short attention span, and social immaturity. The findings showed an interesting trend: the more that the child’s problem posed a threat to the classroom teacher’s control, the more the teacher took the view that the child was intentionally creating the problem and that it was up to the child to control it. Teachers were prepared to develop special programmes and put themselves out for children who were rejected by their peers, who were less able (as distinct from underachieving) and who were shy or socially immature; but they tended to blame, reprimand and punish those who were aggressive, disobedient or underachieving.

Of course, if we are to regard children as persons, then we must also attribute to them intentionality and blameworthiness. To deny these attributes would be to deny children the very characteristics that make them human and capable of ‘responsible’ behaviour. Some children on some occasions, even in nursery and KS1 classes, do seem to be deliberately ‘naughty’ and ‘out to make trouble’, just as some children on some occasions seem to go out of their way to be kind and considerate. None the less, intentionality does not exist in a vacuum. Without denying that problem behaviour is often intentional and sometimes malevolent, we still need to explain how it is that some pupils seem bent on ‘making trouble’ and whether there is something others can do to change the conditions which seem to encourage such behaviour. Moreover, a tendency to see pupils with behaviour problems in terms of pupils with nasty intentions leads to a style of response which does little to ameliorate the problem. The teacher’s classroom management becomes characterised by perpetual nagging, criticising, scolding, admonishing and sometimes punishing. Certainly children sometimes do deserve to be reprimanded and punished, but if they experience these measures as typical responses to their unwanted behaviour they come to resent the imputation of ‘being bad’, and this helps to maintain the problem.

Whereas the term ‘troublemaker’ or ‘naughty pupil’ conveys the idea of bad motives, the term ‘problem pupil’ encapsulates a different set of preconceptions. Here it is some kind of defect or illness that is taken to be the source of the problem, rather than malevolent intentions. There is, as some teachers put it, ‘something wrong with the child’. This medical model has important consequences for the teacher’s responsibility. Children are said to suffer from ‘disorders’ and therefore to be in need of ‘treatment’, which only ‘experts’ can give; and, because the teacher does not have the necessary expertise, the child must be ‘referred’ to someone else with the requisite professional skills, perhaps in a special unit or special school. It is not suggested here that the notion of a disordered personality has no scientific basis, nor that referrals are often inappropriate, but simply that thinking of problem behaviour in terms of ‘problem pupils’ can have unproductive consequences for the management of behaviour in school generally. For although one consequence of the notion of ‘problem pupils’ (in stark contrast to the effects of ‘troublemakers’ imputations) has been the development of more humane and caring attitudes, and although children have undoubtedly often been helped by the treatment received, the result of perceiving problem behaviour in this way as a matter of course is to deny the skill of teachers and parents, encouraging them to believe that they are powerless to effect a change in the behaviour themselves, even with support. Yet experience demonstrates how teachers can bring about remarkable changes in children’s behaviour through appropriate intervention strategies.

The tendency among some teachers to assume that it must be the parents who are responsible for the problem behaviour is another example of focusing on problem people rather than on the behaviour itself. In one study among 428 junior school staff, two out of every three heads or teachers explained the behaviour problems of their pupils in terms of deficiencies in the children’s home circumstances, whilst in only 3.8 per cent of cases did teachers acknowledge that the child’s conduct could be attributed, at least in part, to arrangements in school or classroom management styles (Croll and Moses, 1985). The Elton Committee found a similar reaction among teachers giving reasons for discipline problems, the majority citing family instability, conflict, poverty and parental indifference or hostility to school. Of course the behaviour of many children is a reflection of their home circumstances, but this explanation is often too simplistic. In a study of 343 top KS1 children in London (Tizard et al., 1988), less than one-third of the problems seen by teachers in school had also been seen by parents at home, while only just over one-third of the problems raised by parents had also been noted in school. As the Elton Committee noted:

Researchers have consistently found that when parents and teachers are asked to identify children with behaviour problems in a class they identify roughly the same number, but they are largely different children. The overlap is small. Parents who tell the headteacher that their child ‘doesn’t behave like that at home’ are likely to be telling the truth. Our evidence suggests that many heads and teachers tend to underestimate or even ignore the school-based factors involved in disruptive behaviour.

(DES, 1989, para 4.145, emphasis added)

Thus while some children’s behaviour in school is, at least in part, a consequence of adverse home circumstances, it is misleading to assume that they are the only explanations or even the main ones. As we can all testify from everyday experience, the way individuals behave is affected by the context in which the behaviour is manifest. Just as most of us feel better when the weather is warm and sunny or when we are in the company of people we like or even if we are in a certain room or building, so the behaviour of a child in school is materially affected by matters such as the teacher’s expectations of the child’s behaviour, the teacher’s classroom management and teaching styles, curriculum opportunities and the general ethos of the school.

A danger of focusing on problem people rather than problem behaviour is that teachers and schools may fail to pay sufficient attention to the contribution they themselves are making to maintain, and even generate, the problem behaviour. To see children who present behaviour problems as ‘troublemakers’ is to imply that it is the child who has to accept the main responsibility for changing the problem behaviour; to see such children as ‘problem pupils’ is to imply that only the expert can help; and to lay the blame at the door of ‘problem parents’ is to assume that it is the parent who must take the initiative. Certainly there are many factors, such as those ‘within’ the child or in the home, which are outside the immediate control of teachers and may predispose the child to behave disruptively in school. But the extent to which a child realises such a tendency depends upon the quality of life experienced in school. For instance, children who come from homes where there is a high level of stress due to disharmony, may or may not use the school to vent frustration, depending on how they believe they are valued and have status in the school community. Moreover, the manner in which children presenting behaviour problems are treated in school affects the degree to which their adverse family circumstances affect them, a point recognised in the Department for Education Circular on pupil behaviour:

For some pupils, the school may be the only secure, stable environment. It has been shown that, when children have relationships outside the family in which they feel valued and respected, this helps to protect them against adversity within the family.

(DfE, 1994a, para. 50)

Focus on a range of intervention strategies vs a more circumscribed response

Fortunately, more and more teachers are subscribing to a model which recognises the multifaceted nature of behaviour problems in school. They acknowledge the range of factors that could be affecting pupil behaviour and they therefore minimise the risk of too easily laying the blame – and therefore the responsibility for change – at one door. Children’s behaviour is the product of a number of interacting factors and the relative importance of each varies from one child to another.

In the systems model of pupil behaviour, children in school are seen as functioning within a network of inter-related systems such as the family, the peer group, the classroom, the playground and the school at large. Each system is made up of interacting elements, or aspects of the situation, which influence, and are often influenced by, the child’s behaviour. Thus in the classroom, the elements clearly include the pupils and the teacher, but they also incorporate the curriculum, the resources, the way children are grouped, the rules, furniture layout, and so on – all affecting the child’s behaviour and often being affected by it. The playground can also be regarded as a system whose elements not only comprise the pupils in the child’s own classroom, but also children from other classes. Other elements in the playground system are the playground supervisors, the space available, facilities for play, the design of the playground, and playground customs, rules and sanctions. In the school at large, the elements comprise all the pupils, all the staff and the head, plus the school rules and expectations, the procedures for assembly, the length of lessons and playtimes, the layout of the buildings, specialist facilities, and so on, where again influences work in all directions. The family, neighbourhood and peer group systems contain further sets of elements operating in this interactive way.

The systems model thus encourages us to view the child’s behaviour as a function of numerous interacting elements in various overlapping systems. The practical implications of this are important. To bring about any significant change among pupils presenting problem behaviour, it is clearly not enough to use one strategy; rather the approach must involve changing the nature of the key elements that make up the various systems in which the child operates. Intervention is therefore taken at a number of levels to take account of the range of elements that affect the child’s behaviour in school. In contrast to models of behaviour that are seen in terms of problem people (as examined in the previous section) adherence to the systems model does not entail the belief that all the responsibility for change in pupils’ behaviour must lie with just one party, whether it is the pupils, parents, teachers, support services, or ‘society’. All parties are responsible. However, since the problem behaviour occurs in the school, the initiative needs to be taken by teachers. Naturally, it is those elements within the school system and its sub-systems (classrooms, corridors, playground, lunchroom) which will receive the most attention, but collaboration with parents and maybe other members of the community will have a vital part to play. The systems model also importantly recognises that behaviour problems can often be the outward manifestations of other undiagnosed difficulties such as learning, receptive language, borderline communication or even sensory impairment (Gasgoigne, 1994). Intervention strategies will therefore very likely need to include measures which address such underlying issues.

Focus on pro-active policies and strategies vs reliance on ‘coping’ and ‘crisis management’

A crucial aspect of effective behaviour management is a determination to stand back and examine pedagogic and classroom management styles. The inclusion of ‘pedagogic’ as well as ‘management’ styles here is important since the two are interrelated. As we saw at the end of the last section, there is a strong overlap between factors that contribute to effective pupil lea...